When 3I/ATLAS swept past the Sun in late October 2025, it became only the third confirmed visitor from interstellar space ever detected. Unlike the mysterious ‘Oumuamua, which revealed almost nothing about itself during its brief flyby in 2017, or even 2I/Borisov which appeared in 2019, this latest interstellar traveler arrived with perfect timing for detailed study.

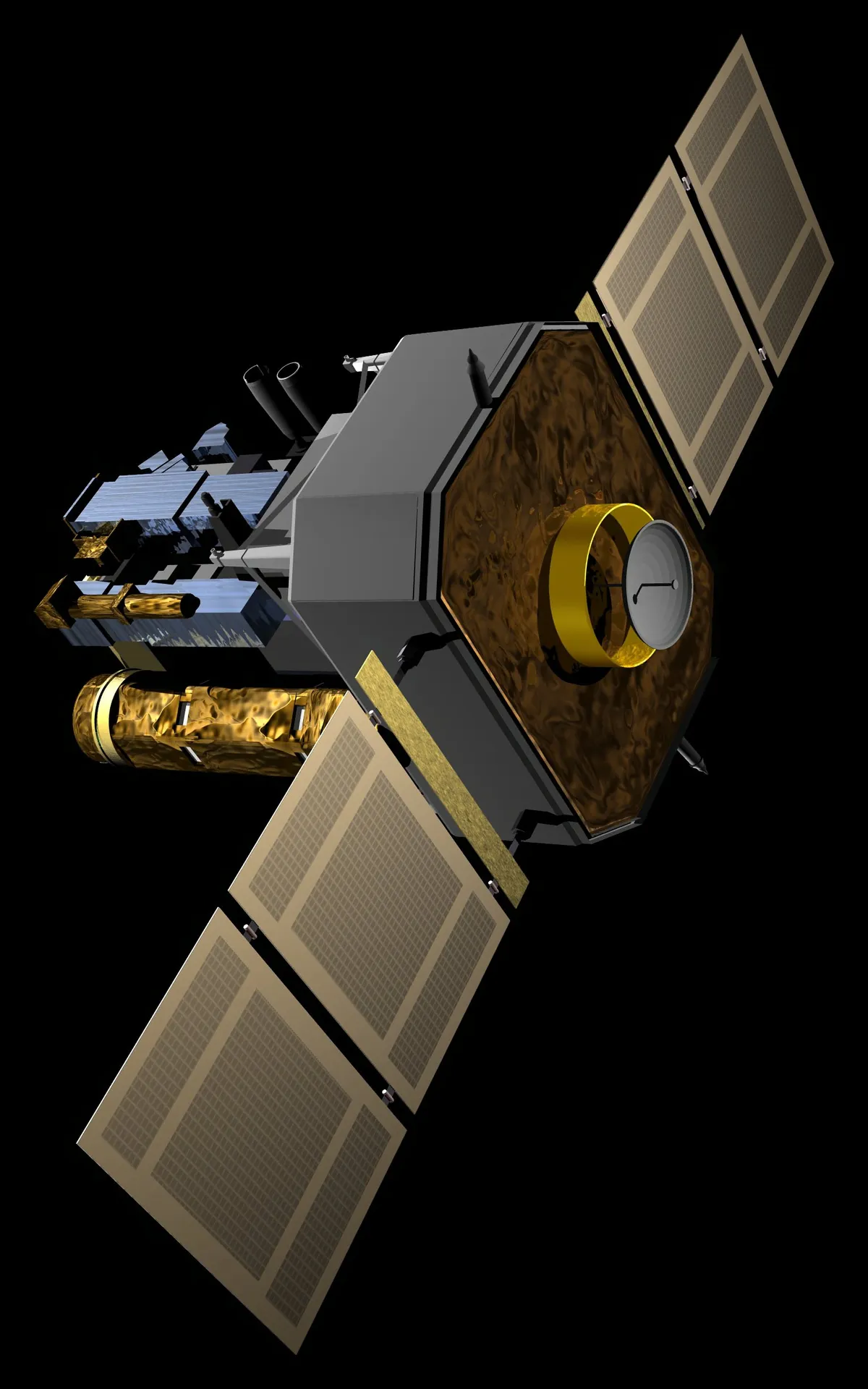

Among those watching was an unlikely observer. The Solar and Heliosphere Observatory, or SOHO, has spent nearly 30 years staring at the Sun from its orbital position 1.5 million kilometres from Earth. But SOHO carries a camera called SWAN that wasn’t designed to look at the Sun at all. Instead, it watches for a specific wavelength of ultraviolet light emitted by hydrogen atoms, creating an all sky map of hydrogen scattered throughout the Solar System.

Nine days after 3I/ATLAS reached perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun on 30 October, SWAN began detecting a distinctive hydrogen glow surrounding the comet. This wasn’t just any hydrogen. When sunlight strikes water molecules streaming from a comet’s nucleus, it breaks them apart, releasing hydrogen atoms that then glow in ultraviolet light. By measuring this glow, astronomers can work backward to calculate how much water the comet is producing.

An artist's impression of the SOHO spacecraft. ( Credit : NASA/ESA/Alex Lutkus)

An artist's impression of the SOHO spacecraft. ( Credit : NASA/ESA/Alex Lutkus)

The measurements revealed something remarkable. On 6 November, when the comet had traveled out to 1.4 astronomical units from the Sun, it was spewing water at a rate of 3.17 × 10²⁹ molecules per second. That’s 317 followed by 27 zeros. To put it another way, imagine filling an Olympic swimming pool every few seconds, and you’re getting close to the scale of water production from this relatively small icy nucleus.

What makes these observations particularly valuable is their timing. Most studies of 3I/ATLAS happened before perihelion, when the comet was approaching the Sun and beginning to heat up. The SWAN observations captured what happened afterward, as the comet moved away and its activity began declining. Over the following weeks, water production dropped steadily, falling to between 10 and 20 trillion trillion molecules per second by early December, about 40 days after perihelion.

This decrease follows a pattern that astronomers recognise from Solar System comets. As a comet moves farther from the Sun, the reduced heating means less ice sublimates from the nucleus, and activity winds down. The fact that 3I/ATLAS behaves this way suggests that despite traveling through interstellar space for potentially millions of years, it hasn’t fundamentally changed from the icy bodies that formed in our own Solar System’s distant past.

The technique used to measure this water production has proven itself remarkably reliable. First developed over two decades ago and refined through observations of more than 90 different comet apparitions, the method combines SWAN’s hydrogen measurements with daily readings of solar ultraviolet output and corrections for the Sun’s rotation. Each piece of the calculation matters, because the fluorescence rate depends on how much ultraviolet light the Sun is emitting at any given moment.

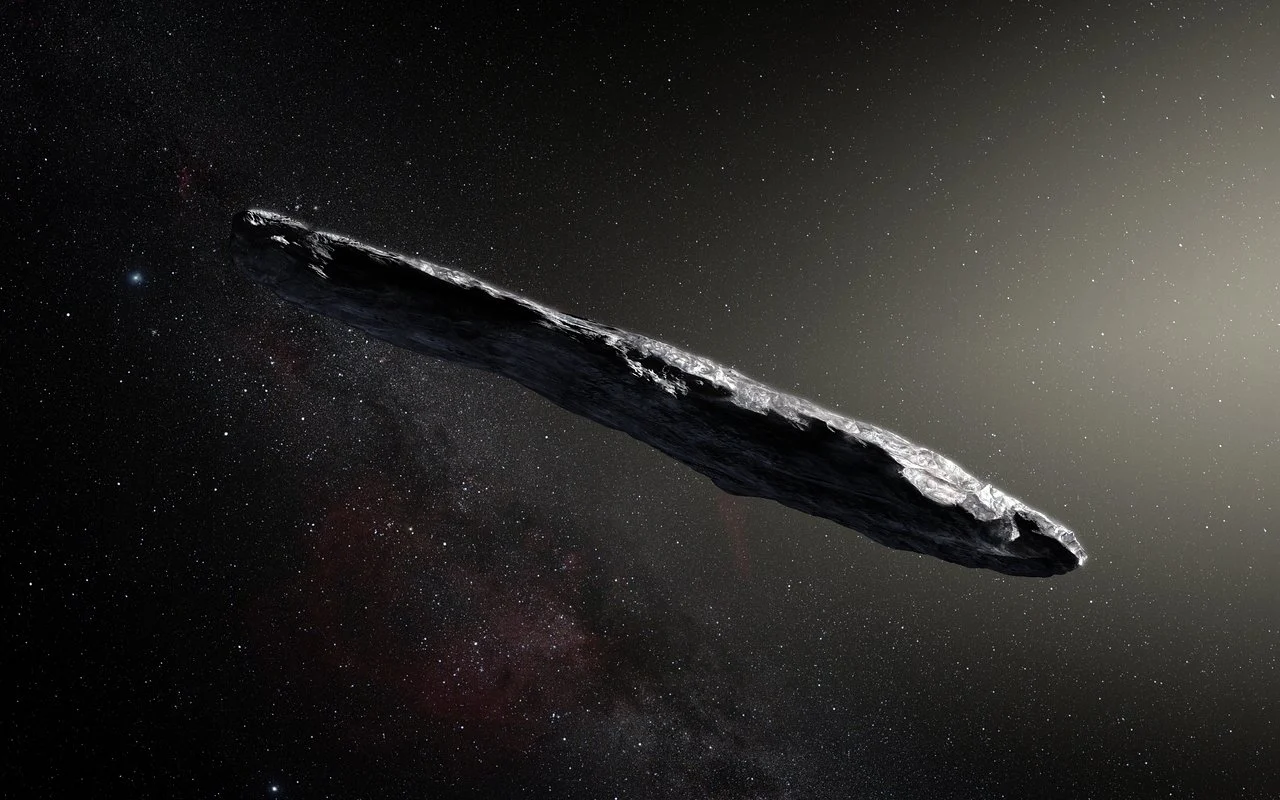

*Interstellar visitor Oumuamua*

*Interstellar visitor Oumuamua*

For 3I/ATLAS, these measurements serve a purpose beyond simple curiosity about a single comet. This object formed in a planetary system around another star, possibly billions of years ago. By studying its composition and behaviour, it’s possible learn about the conditions in that distant stellar neighbourhood, compare them to our own Solar System’s formation, and better understand the diversity of planetary systems throughout the Galaxy.

The comet’s substantial water production also raises intriguing questions about its nucleus size and surface activity. Based on Hubble Space Telescope observations, the nucleus diameter is somewhere between 440 meters and 5.6 kilometres. If water is sublimating directly from the surface, a significant fraction of that surface would need to be active, possibly around 20 percent, which is much higher than the typical 3 to 5 percent seen in most Solar System comets.

3I/ATLAS now leaves our Solar System behind, travelling for millennia before approaching another star, but thanks to SWAN and the other instruments that studied it, we’ve captured a detailed snapshot of this messenger from the depths of space during its brief visit to our own neighbourhood.

Source : Water Production of Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS from SOHO/SWAN Observations after Perihelion

Universe Today

Universe Today