In our galaxy, a supernova explodes about once or twice each century. But historical astronomical records show that the last Milky Way core-collapse supernova seen by humans was about 1,000 years ago. That means we've missed a few.

But with the Vera Rubin Observatory poised to begin its decade-long Legacy Survey of Space and Time, no supernova is safe from our prying astronomical eyes.

We all know that core-collapse supernovae are what happens when stars several times more massive than the Sun expend their fuel. Eventually the star's outward pressure is exceeded by its inward gravity, and the star collapses on itself. Then it explodes outward in a massive display of repressed energy that can light up the sky for months.

Astrophysicists are interested in supernovae because of their power and the important role they play in the cosmos. They're cosmic forges that produce the heavy elements needed for rocky planets to form and for living things to use in their tissues. They're also important in understanding stellar evolution, and how neutron stars and black holes form. And supernovae are important indicators in the cosmic distance ladder. Their extreme environments are also like laboratories where theories about nuclear reactions and neutrino phsyics can be tested.

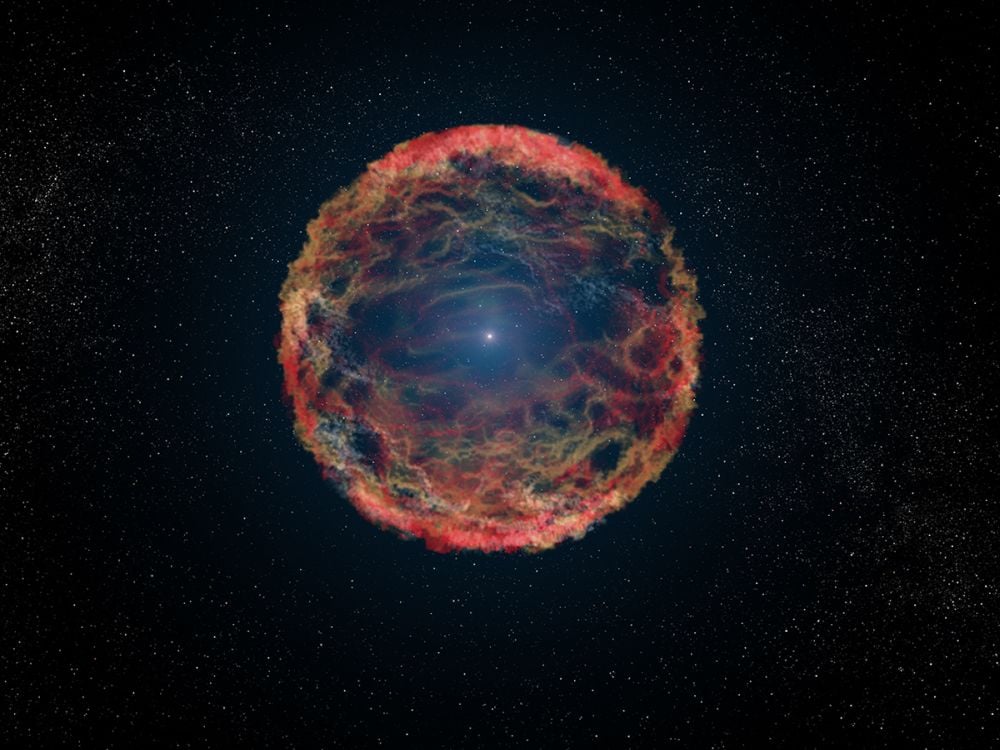

The more core-collapse supernovae (CCSNe) astrophysicists can detect, the more they can learn. While humanity has observed other Milky Way SNe more recently, like the Type Ia Kepler's Supernova in 1604, it's been about one millennia since the last CCSNe was detected. That was SN 1054, a CCSNe that created the Crab Nebula.

*When SN 1054 exploded, it left the Crab Nebula supernova remnant behind. The Crab Nebula is one of the most well-studied objects in astronomy. It's been expanding since its progenitor star exploded and is now six light-years wide. This is a composite image from the Hubble Space Telescope. Image Credit: By NASA, ESA, J. Hester and A. Loll (Arizona State University) - HubbleSite: gallery, release., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=516106*

*When SN 1054 exploded, it left the Crab Nebula supernova remnant behind. The Crab Nebula is one of the most well-studied objects in astronomy. It's been expanding since its progenitor star exploded and is now six light-years wide. This is a composite image from the Hubble Space Telescope. Image Credit: By NASA, ESA, J. Hester and A. Loll (Arizona State University) - HubbleSite: gallery, release., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=516106*

New research submitted to the Open Journal of Astrophysics shows how the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is well-positioned to observe many more SNe than in the near past. It's titled "Uncovering the Next Galactic Supernova with the Vera C. Rubin Observatory," and the lead author is John Banovetz. Banovetz is from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Physics Department at Brookhaven National Laboratory. The research is currently available at arxiv.org.

"Supernovae are observed to occur approximately 1-2 times per century in a galaxy like the Milky Way," the researchers write. "Based on historical records, however, the last core-collapse galactic supernova observed by humans occurred almost 1,000 years ago. Luckily, we are well positioned to catch the next one with the advent of new neutrino detectors and astronomical observatories."

Neutrinos play an important role in supernova detection. While the eye-catching visible light is the most easily-observed part of a CCSN, that light doesn't tell the whole tale. When a massive star collapses as a SN, it forms a neutron star. All that gravitational energy has to go somewhere, and neutrinos carry away about 99% of the energy. The visible light and the kinetic energy in the explosion only account for about 1%.

Neutrinos may be fickle, but they play an important role in SNe. They're also the first signal that a Type II SN is exploding. While the shock wave and the visible light take hours to move and propagate through the star's outer shells, neutrinos can't be restrained: they escape from the explosion immediately.

Unfortunately, neutrinos are difficult to detect. They're sometimes called "Ghost Particles" because their electrical charge is zero and they have almost no mass. They travel unimpeded from the exploding star out in all directions, some toward Earth. So our neutrino detectors can detect the supernova neutrino signal long before the explosion's light arrives. And the detectors can alert the Rubin Observatory.

"Neutrino observatories can provide unprecedented triggers for a galactic supernova event as they are likely to see a supernova neutrino signal anywhere from minutes to days before the shock breakout causes the supernova to brighten in optical wavelengths," the authors explain. "Given its large etendue, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is ideally positioned to rapidly localize the optical counterpart based on the neutrino trigger."

To do that, the Rubin needs to quickly take the neutrino trigger signal and scan the heavens for the electromagnetic counterpart. With its wide field of coverage and its relatively deep yet quick exposures, "The Vera C. Rubin Observatory is an ideal facility to detect the EM counterpart from a neutrino trigger," the authors write.

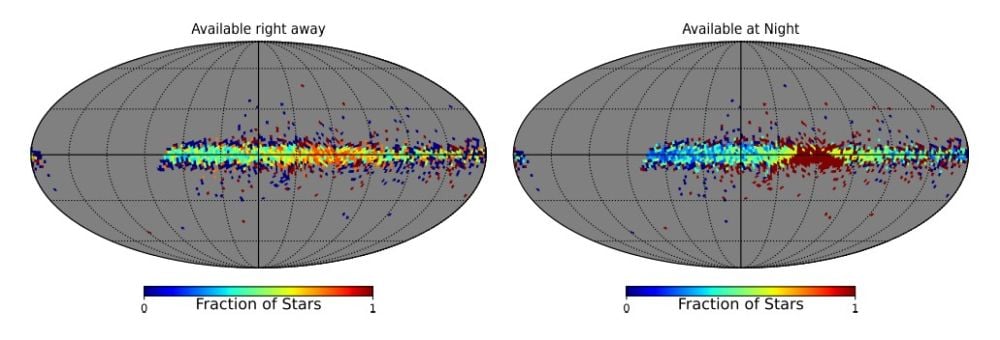

To test the Rubin's ability to find these SNe, the researchers created a simulated model of the Milky Way with different CCSNe candidates at different distances and extinctions. Overall, the model contained 100,000 simulated SNe at random locations, either at night and available to observe right away, or during the day and available to be observed that night.

*This figure from the research shows the results of placing 100,000 CCSN at a random time of the year and in random locations in the Milky Way. Left: Fraction of stars that explode at night and are available to observe (Available right away). Right: Fraction of stars that explode during the day but are available at night (Available at Night). Image Credit: Banovetz et al. 2026. OJA*

*This figure from the research shows the results of placing 100,000 CCSN at a random time of the year and in random locations in the Milky Way. Left: Fraction of stars that explode at night and are available to observe (Available right away). Right: Fraction of stars that explode during the day but are available at night (Available at Night). Image Credit: Banovetz et al. 2026. OJA*

The results were impressive, and suggest that the Rubin Observatory is poised to advance the science of CCSNe.

"We find that the observatory is ideal for initial localization of nearly all observable supernova triggers and has a 57-97% chance of catching any supernova based on theoretical stellar mass density predictions and observations," the authors write.

But like other telescopes and observatories, the Vera Rubin uses filters, and they can't all be used at the same time. The researchers say that if the Milky Way's next CCSNe explodes during the Rubin's 10-year LSST, then it's almost guaranteed that the observatory will detect it. A 30 second exposure is all that's required, though the guarantee only extends to its two reddest filters, and not the bluer filters.

There are other filtering difficulties, however, based on how distant the SN is. "A large remaining uncertainty is the time-difference between the explosion and SBO (shock break-out, when the explosion breaks out of the supernova and travels more freely through space), which determines the lag with which the EM counterpart arrives," the researchers explain. "As the time between the alert and the SBO could range from mere minutes to hours, after the time it takes to slew to the target, a decision will need to be taken as to when and if a filter change should be made to a redder band to increase the probability of catching the SBO."

The researchers say that decisions about filter changes will depend on the filter in use at the time, and the SN's distance. "Optimizing this process will be the focus of future work," they write.

The researchers say that this study serves as a framework for observing the next CCSN, but they also acknowledge that there are many challenges left to still be addressed.

"One of the most important is locating the CCSN in a crowded field, since the galactic plane can have thousands stars per CCD detector," the authors write. Testing how the alert function performs in these crowded fields is necessary, as is ongoing work into processing pipelines. Processing pipelines are a series of steps designed to function in a specific astronomical setting and are an important part of modern astronomy.

"Combined with current and future neutrino detectors, soon everything will be in place to quickly locate the next galactic CCSN should it occur during the lifetime of the LSST," the researchers explain. "This will give us an unprecedented view into both the CCSN process and neutrino astrophysics," they conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today