In recent years, astrophysicists have discovered supermassive black holes (SMBH) in the early Universe that are much larger than they should be. Black hole growth is restrained by the Eddington Mass Limit, a cap on the growth rate of black holes. But objects can exceed this limit in certain circumstances, and that's called super-Eddington accretion. can Super-Eddington accretion explain these early SMBH?

As an SMBH draws material into its accretion disk, the material in the disk heats up. This exerts outward radiation pressure that limits the amount of material the SMBH can accrete. The SMBH's gravity is pulling material in while the radiation is pushing material away. That's the Eddington limit.

Super-Eddington accretion is when the material in an SMBH's disk is so intense that radiation gets trapped in it. The radiation is swept up into the SMBH before it can push gas away. The excess radiation can also be beamed away in jets, and both allow super-Eddington accretion. Astrophysicists want to know if Super-Eddington can explain the surprisingly massive SMBH in the early Universe.

A team of scientists have discovered a quasar, the extremely luminous counterpart to a SMBH, with puzzling multiwavelength emissions. It's emitting both x-rays and radio waves, and it could be the key to understanding super-Eddington accretion in the early cosmos.

Their work is published in The Astrophysical Journal as "Discovery of an X-Ray Luminous Radio-loud Quasar at z = 3.4: A Possible Transitional Super-Eddington Phase." The lead author is Sakiki Obuchi from the Department of Physics at Waseda University in Tokyo.

As a SMBH draws material into its accretion disk, the material heats up and produces x-rays. When SMBHs develop polar jets, those produce radio emissions. As the researchers point out, their discovered SMBH produces both in abundance. "We report the multiwavelength properties of eROSITA Final Equatorial Depth Survey (eFEDS) J084222.9+001000 (hereafter ID830), a quasar at z = 3.4351, identified as the most X-ray luminous radio-loud quasar in the eFEDS field," they explain. eROSITA is an x-ray instrument on the Spektr-RG space observatory.

This quasar is from only about 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, and it's accreting gas at almost 15 times the Eddington Limit. The problem is, its super-Eddington accretion should prevent it from being so luminous in x-rays and so bright in radio waves. Much of that energy should be drawn into the black hole. These findings hint at an unknown mechanism in SMBH accretion.

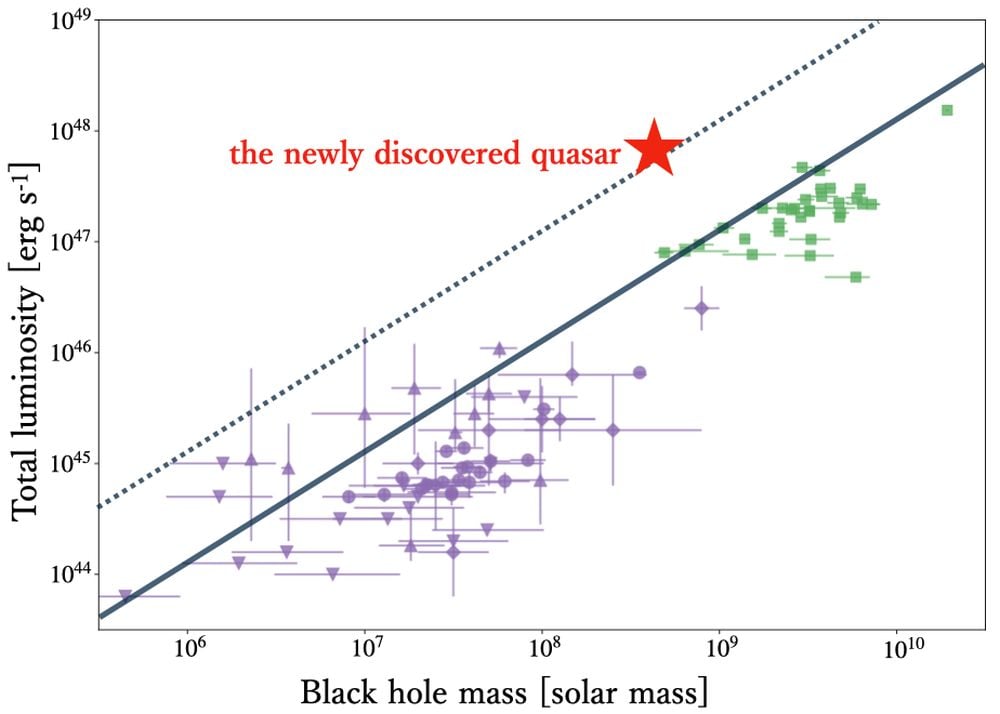

This figure shows black hole mass on the x-axis, and luminosity, which traces growth rate, on the y-axis. ID830 is off by itself when plotted with other black holes. The solid line indicates the theoretical upper limit of the black hole accretion rate (the Eddington limit), while the dashed line indicates gas accretion at ten times this limit (super-Eddington). Image Credit: National Astronomical Observatory Japan.

This figure shows black hole mass on the x-axis, and luminosity, which traces growth rate, on the y-axis. ID830 is off by itself when plotted with other black holes. The solid line indicates the theoretical upper limit of the black hole accretion rate (the Eddington limit), while the dashed line indicates gas accretion at ten times this limit (super-Eddington). Image Credit: National Astronomical Observatory Japan.

"One possible origin of the X-ray excess is contamination from jet-linked components," the authors write. Previous research shows that electrons reaching relativistic speeds in these jets can transfer some of their energy to lower energy photons during collisions. These photons then emit x-rays.

The authors write that "ID830 represents a rare example of a super-Eddington, radio-loud quasar exhibiting an extreme X-ray excess."

The researchers think that ID830 could be in a transitional phase after a burst of accretion, in between super-Eddington accretion and sub-Eddington accretion. The phase is likely very short-lived. They think that a sudden accretion burst of inflowing gas pushed the SMBH into super-Eddington, and for a short period of time, a bright x-ray corona and radio-loud jets were both energized. But that didn't last long before the system returned to equilibrium.

*In this artist's illustration of a supermassive black hole, the hot corona appears as pale, conical swirls above the accretion disk. Image Credit: NASA/Aurore Simonnet (Sonoma State Univ.)

*In this artist's illustration of a supermassive black hole, the hot corona appears as pale, conical swirls above the accretion disk. Image Credit: NASA/Aurore Simonnet (Sonoma State Univ.)

If these results are correct, then they can explain the large masses of SMBH at high redshifts.

"This discovery may bring us closer to understanding how supermassive black holes formed so quickly in the early Universe," lead author Obuchi said in a press release. "We want to investigate what powers the unusually strong X-ray and radio emissions, and whether similar objects have been hiding in survey data."

These results also touch on black hole feedback. ID830's powerful radio emissions suggests that it has extremely powerful jets. These jets can influence their host galaxy by injecting energy into star-forming gas. This can regulate star formation, meaning that there could be a link between super-Eddington accretion in SMBH and the star-formation rate in their galaxies.

ID830's scientific importance extends beyond potentially explaining the early Universe's surprisingly massive SMBHs. It, and others like it, could be important test cases for understanding super-Eddington accretion and SMBH jet-driven feedback.

Universe Today

Universe Today