Our middle-aged Solar System is mostly calm and stable, with fully-formed planets staying in their lanes while placidly orbiting the Sun. But it wasn't always this way. The Solar System had a tempestuous youth, full of collisions that shattered many bodies into tiny pieces. The debris-strewn main asteroid belt is evidence of this.

Other solar systems were likely the same. There seems to be no way around it. Evidence from the Fomalhaut system illustrates this.

Fomalhaut is actually a triple star system. Fomalhaut B is a main-sequence star, and Fomalhaut C is a red dwarf star. But the primary star, Fomalhaut A, is the most massive star. It's more massive and more luminous than the Sun. It's also young, only about 400 million years old.

In 2005, astronomers directly imaged light from the enormous, elliptical belt of dust around Fomalhaut A. The researchers said it was from the collisions between comets and asteroids orbiting the star.

In 2008, astronomers announced the discovery of an exoplanet candidate named Fomalhaut b in that same ring. However, subsequent research showed that it was a dust cloud from colliding planetesimals.

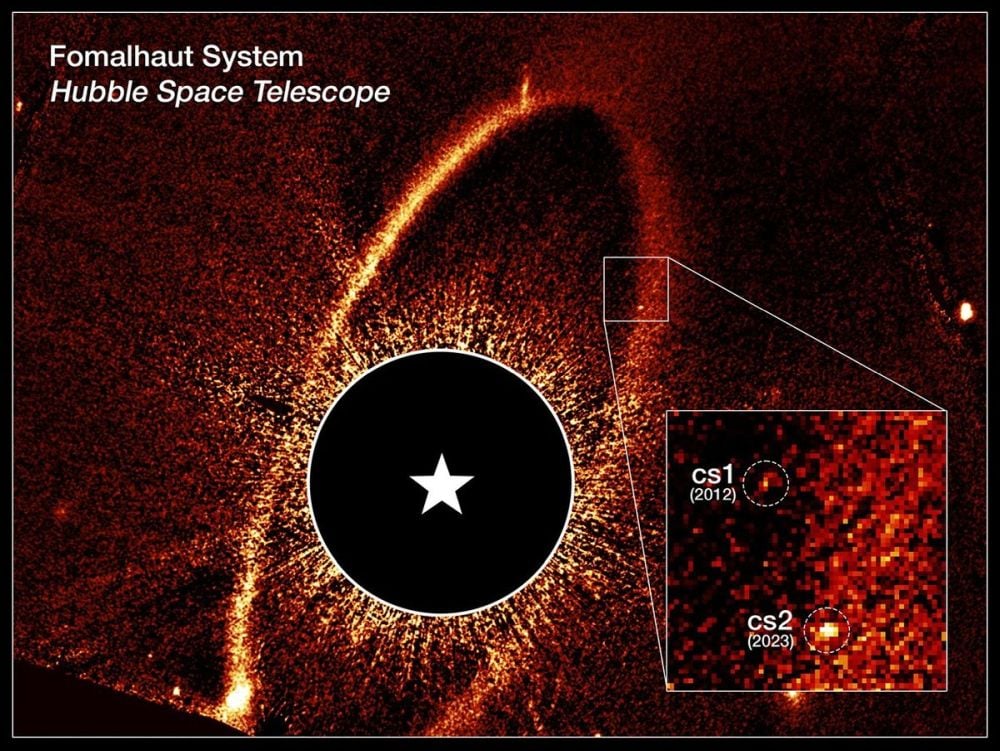

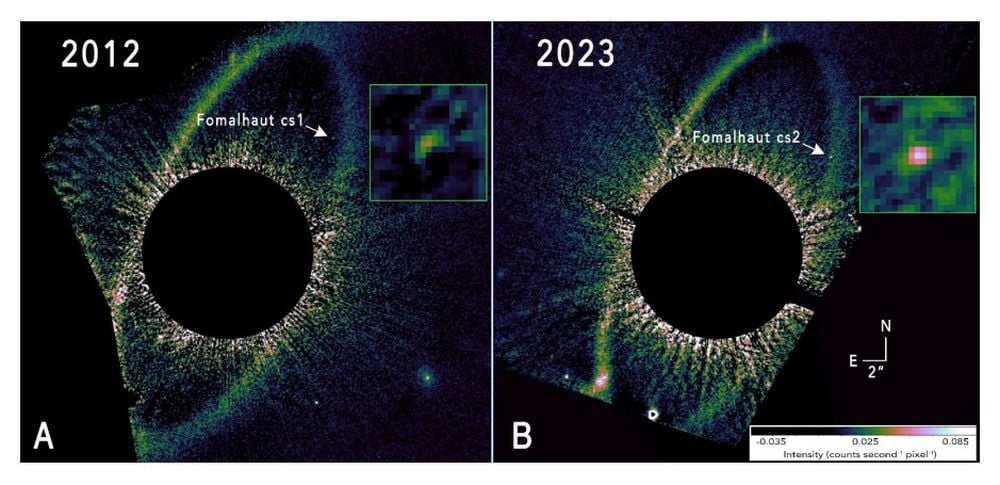

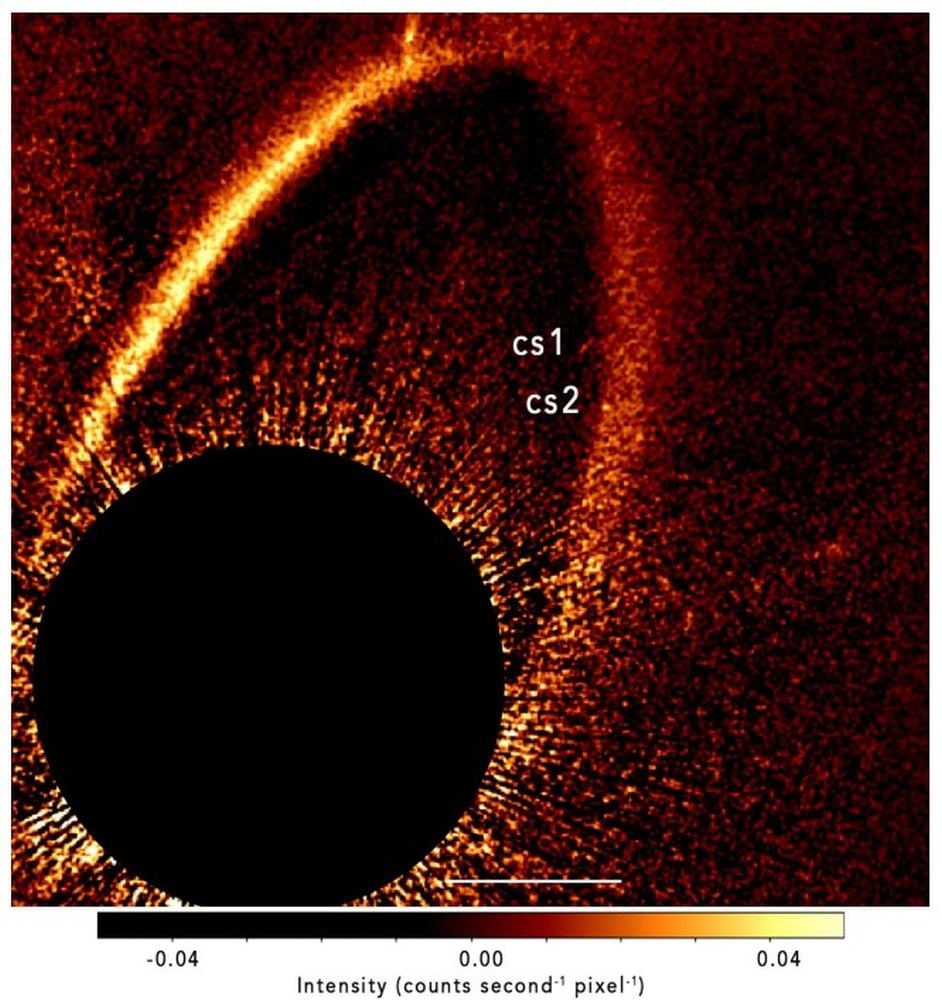

Astronomers have stuck with it, and many years later Hubble observations identified a second dust clump around Fomalhaut. The objects are now called circumstellar source 1 (cs1) and circumstellar source 2 (cs2).

New research in Science appears to have figured out what's behind the sources: collisions between planetesimals. It's titled "A second planetesimal collision in the Fomalhaut system," and the lead author is Paul Kalas, an Adjunct Professor of Astronomy at UC Berkeley.

"The nearby star Fomalhaut is orbited by a compact source, Fomalhaut b, which has previously been interpreted as either a dust-enshrouded exoplanet or a dust cloud generated by the collision of two planetesimals," Kalas and his co-researchers write. "Such collisions are rarely observed but their debris can appear in direct imaging."

Fomalhaut is only about 25 light-years away and is a frequent target for astronomical observations. Cs2 didn't show up in the team's previous Hubble observations, but when they observed it in 2023, there it was. Cs1 did not appear in those images, supporting the idea that it was a collision-generated dust cloud that had since dissipated.

This new detection helps make it clear that cs1 was not an exoplanet. "The appearance of Fom cs2 supports the interpretation that cs1 was a dust cloud from a planetesimal collision, not reflected light from dust around an exoplanet," the authors write in their research. "We interpret both cs1 and cs2 as evidence of a collisional process in the Fomalhaut planetary system."

Cs2's appearance is rather sudden for a region that's observed so often. It suggests that collisions are active and ongoing, which isn't surprising for a young solar system.

*This figure shows optical images of the Fomalhaut system in 2012 and 2023 from the Hubble Space Telescope. A coronagraph blocks out the starlight. Cs1 appears in the 2012 image but not in the 2023 image. However, cs2 appears in the second image. Image Credit: Kalas et al. 2025. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adu6266*

*This figure shows optical images of the Fomalhaut system in 2012 and 2023 from the Hubble Space Telescope. A coronagraph blocks out the starlight. Cs1 appears in the 2012 image but not in the 2023 image. However, cs2 appears in the second image. Image Credit: Kalas et al. 2025. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adu6266*

“This is certainly the first time I’ve ever seen a point of light appear out of nowhere in an exoplanetary system,” said principal investigator Paul Kalas of the University of California, Berkeley. “It’s absent in all of our previous Hubble images, which means that we just witnessed a violent collision between two massive objects and a huge debris cloud unlike anything in our own Solar System today. Amazing!"

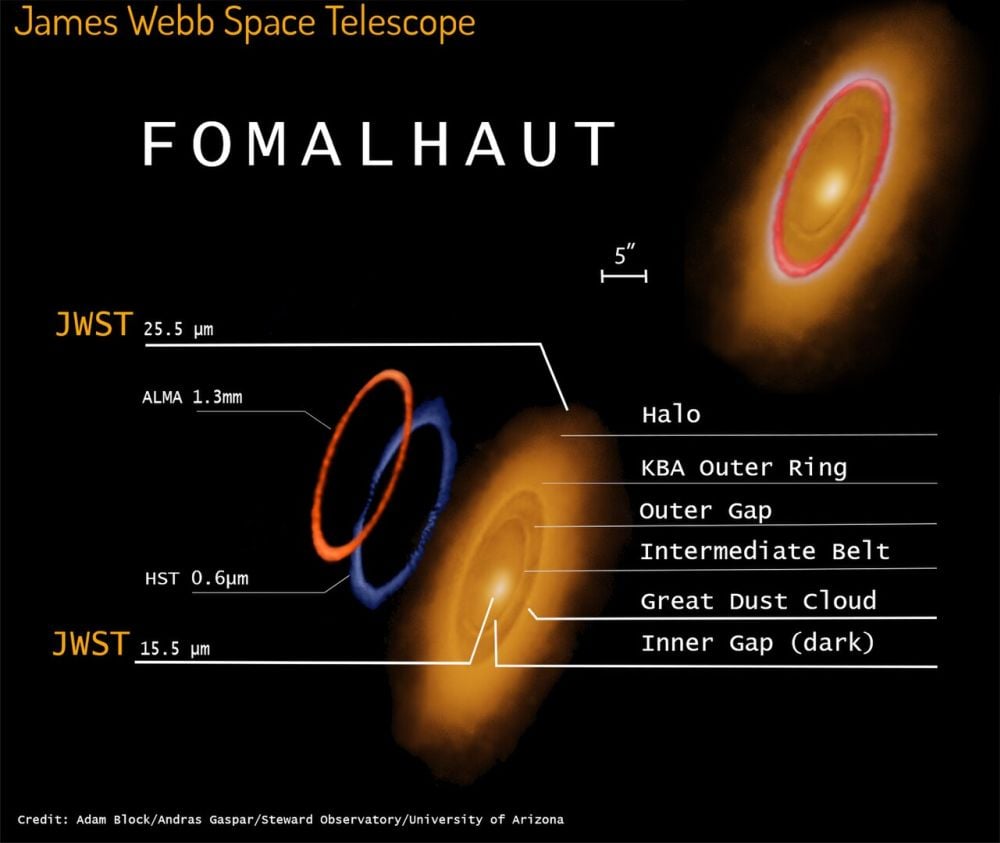

The puzzling thing about both cs1 and cs2 is their proximity to one another. If young solar systems are so random and chaotic, we should expect to find these collision clouds more widely separated from one another. Instead, they're both on the inner part of the outer debris ring surrounding Fomalhaut.

*This graphic shows the features of the disk and rings around Fomalhaut, as revealed by different telescopes. Image Credit: By Ngc1535 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=131685936*

*This graphic shows the features of the disk and rings around Fomalhaut, as revealed by different telescopes. Image Credit: By Ngc1535 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=131685936*

They pair of collisions also occurred in rapid succession. Can this tell astronomers something about young solar systems?

“Previous theory suggested that there should be one collision every 100,000 years, or longer. Here, in 20 years, we've seen two,” explained Kalas. “If you had a movie of the last 3,000 years, and it was sped up so that every year was a fraction of a second, imagine how many flashes you'd see over that time. Fomalhaut’s planetary system would be sparkling with these collisions.”

While finding rocks smashing into one another 25 light-years away could seem irrelevant and inconsequential, it's not. All natural events are consequential in one way or another.

Rocky collisions are an integral part of solar system formation, and of the terrestrial planet formation process. Many rocks smashed into one another and produced debris clouds in our Solar System, and without all of that, Earth wouldn't be here. Neither would we.

Even though it's only one pair of collisions, it's still an event with relevant data.

“The exciting aspect of this observation is that it allows researchers to estimate both the size of the colliding bodies and how many of them there are in the disk, information which is almost impossible to get by any other means,” said study co-author Mark Wyatt at the University of Cambridge. “Our estimates put the planetesimals that were destroyed to create cs1 and cs2 at just 30 kilometres in size, and we infer that there are 300 million such objects orbiting in the Fomalhaut system.”

“The system is a natural laboratory to probe how planetesimals behave when undergoing collisions, which in turn tells us about what they are made of and how they formed,” explained Wyatt.

They also expect that a 30 km planetesimal will suffer about 900 shattering events before it experiences a catastrophic impact. This provides some insight into the amount of dust in the debris disk. "While this is a simplified estimate, because shattering impacts erode some fraction of a planetesimal’s mass, it indicates that there are many times more shattering collisions than catastrophic collisions," they explain. Shattering collisions create dust that accumulates as regolith on the planetesimals, and is then released into the disk during catastrophic collisions. This dust is in the cloud found in the Hubble images.

The two collisions occurred only 20 years apart, which doesn't seem random. "The temporal and spatial proximity of Fom cs1 and cs2 implies that the collisions might not be random," the authors explain. The intermediate belt is misaligned to the outer belt, and the authors considered whether this could be generating collisions beyond what is random. However, that idea didn't stand up to scrutiny. Instead, they wonder if an exoplanet could be responsible. "An alternative dynamical pathway could involve planetesimals trapped in mean-motion resonances with an exoplanet, producing a higher number density and collision rate in the cs1/cs2 region," they write.

*This figure is a composite image of the 2012, 2013, and 2023 observations. It shows the relative positions of cs1 and cs2 (white labels) a decade apart. Image Credit: Kalas et al. 2025. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adu6266*

*This figure is a composite image of the 2012, 2013, and 2023 observations. It shows the relative positions of cs1 and cs2 (white labels) a decade apart. Image Credit: Kalas et al. 2025. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adu6266*

But beyond what these observations can teach us about planetesimals and collisions in young solar systems, cs1 and cs2 also have something helpful to tell us about our search for exoplanets.

“Fomalhaut cs2 looks exactly like an extrasolar planet reflecting starlight,” said Kalas. “What we learned from studying cs1 is that a large dust cloud can masquerade as a planet for many years. This is a cautionary note for future missions that aim to detect extrasolar planets in reflected light."

Kalas and his team are going to use the Hubble to keep tabs on cs2 over the next three years. The changes it undergoes will add to the knowledge of planetesimal collisions. Will it fade? Will it brighten somehow? Will its dust gradually spread and make the entire disk reflect brighter?

“We will be tracing cs2 for any changes in its shape, brightness, and orbit over time,” said Kalas, “It’s possible that cs2 will start becoming more oval or cometary in shape as the dust grains are pushed outward by the pressure of starlight.”

They'll also use the JWST's NIRCam to watch cs2. It can tell the researchers about the size of the dust grains, and even if water ice is present. The behaviour of water in young solar systems and it accumulation on planets is an ongoing topic of research, for obvious reasons.

Universe Today

Universe Today