Carl Sagan famously said that “We’re all made of star-stuff”. But he didn’t elaborate on how that actually happened. Yes, many of the molecules in our bodies could only have been creative in massive supernovae explosions - hence the saying, and scientists have long thought they had the mechanism for how settled - the isotopes created in the supernovae flew here on tiny dust grains (stardust) that eventually accreted into Earth, and later into biological systems. However, a new paper from Martin Bizzarro and his co-authors at the University of Copenhagen upends that theory by showing that much of the material created in supernovae is captured in ice as it travels the interstellar medium. It also suggests that the Earth itself formed through the Pebble Accretion model rather than massive protoplanets slamming together.

The key to the paper is Zirconium - not an element typically associated with cosmochemistry. However, it has one particular isotope - Zr-96 - that is only created in supernovae. So Dr. Bizzarro and his team decided to look for evidence of it in some meteorites to see where in their structure the Zr-96 was hiding.

To do so, they took samples of a wide range of types of meteorites, and exposed them to weak acetic acid. This dissolved any material associated with water (including clays) while leaving the hard “rocky” grains of the meteorite’s body untouched.They then measured the concentrations of Zr-96 in the dissolved water as well as the rocky residue.

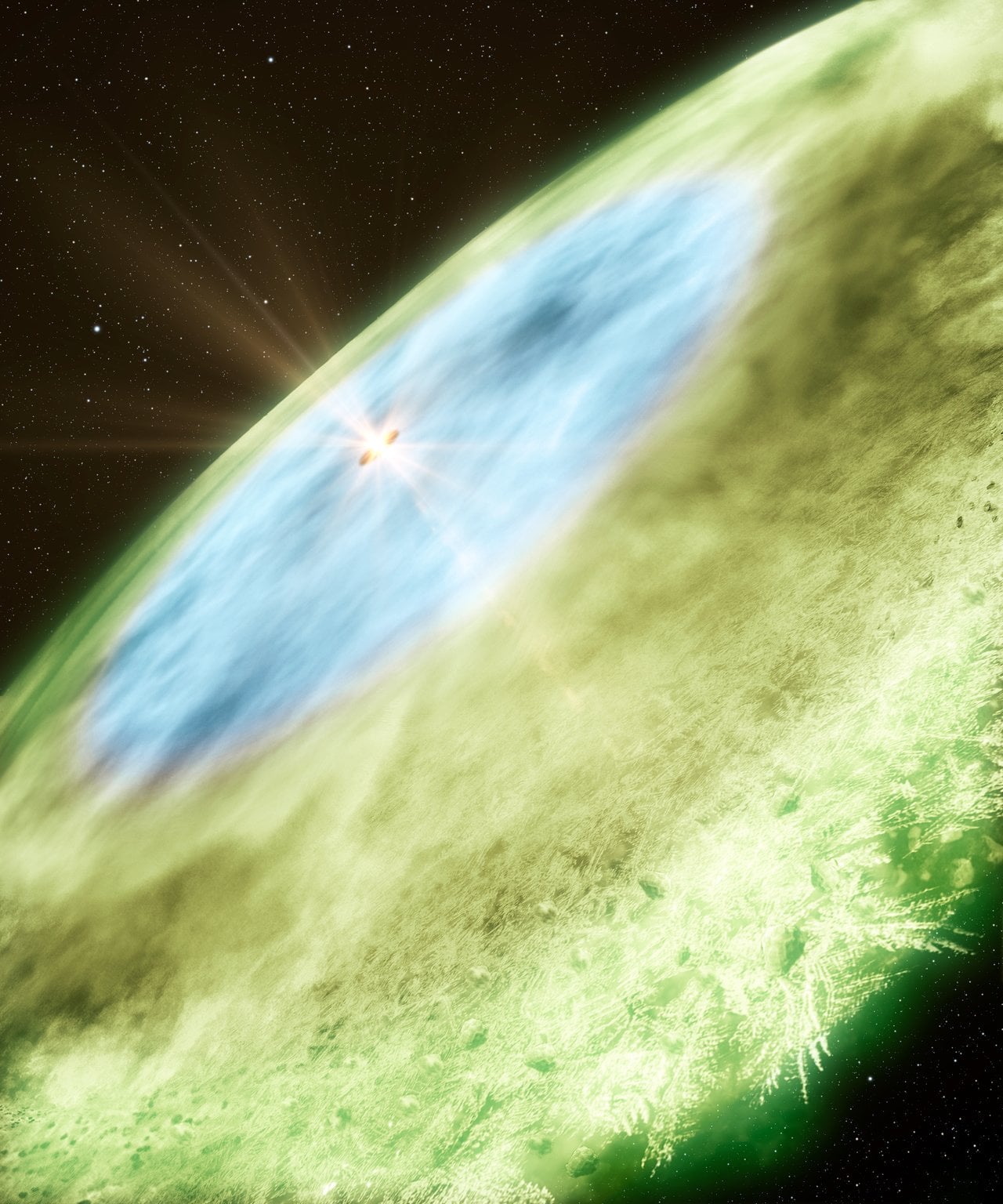

Fraser discusses how a cascade of star destruction created out world.They found that concentrations of Zr-96 were up to 5000 ppm higher in the leachates (i.e. the parts dissolved in acid) than in the rock. This seems to prove that ice was the main transport mechanism for the supernovae remnants. When a supernova explodes, it doesn’t just eject stardust - some of the material was atomized and embedded directly in icy particles.

That theory has implications for planetary formation models. The closer a planet forms to its parent star, the more likely the ice grains containing these supernovae remnants are to burn off. Therefore, closer in planet, such as Earth, Venus, and Mercury, are notably lacking in isotopes that were created in supernovae. On the other hand, planets that are farther out, such as Neptune or Uranus, would be abundant in these isotopes. This aligns precisely with what has been called the Solar System’s “mixing line” - the farther out from the Sun a planet is, the less supernova isotopes it has - and that line is linear, which would fit well with the idea that its caused by melting ices.

Take this analysis a step further, though, and it has implications on planetary formation. Earth is relatively bereft of Zr-96, especially compared to the asteroids used in the study. By implication, if Earth was formed by asteroids (of whatever size) smashing together, it likely would have had a higher concentration of that particular isotopes. On the other hand, if it formed via “pebble accretion”, where tiny icy pebbles drift across the “snow line” and their ice sublimates, those sublimated gases would have taken the Zr-96 with it, meaning that Earth wouldn’t have accrued much of it - which is what the data shows. Therefore, this work lends further argument to the idea that Earth accreted out of pebbles with the Zr-96 burned off, rather than by larger asteroids or planetesimals that managed to hold onto their supernovae isotopes.

Carl Sagan's famous lecture on how we are made of star-stuff. Credit - Carl Sagan / Cosmos / carlsagandotcom YouTube ChannelAnother finding from the paper involved Calcium-Aluminum-rich Inclusions (CAIs) that are some of the oldest materials in the solar system. When the researchers looked at the CAIs in the meteorites, they found that the levels of Zr-96 varied widely - some had a lot and some had very little. This implies that they formed in very different environments - likely in different parts of the protoplanetary disc that prevailed in our solar system before the planets formed.

When the Zr-96 was stripped from its dust particles in the early solar system’s disk, it created a “stratified” accretion disc, where the “lighter” gas particles would move towards either the top of bottom part of the “pancake” structure of the disc, while the heavier dust grains would form nearer the middle of it. CAIs would form in both parts, and would accrue more or less Zr-96 depending on what part of the stratified disc they were formed in.

Both of these theories are interesting, and will need further study. If proved correct, this paper might one day be seen as a landmark study in both pre-planetary chemistry as well as planetary formation theory. No matter whether it is or not, we should all still be able to appreciate being made out of star-stuff - whether it was originally captured in ice or not.

Learn More:

M. Bizzarro et al - Interstellar Ices as Carriers of Supernova Material to the Early Solar System

UT - Learning More About Supernovae Through Stardust

UT - Supernovae are the Source of Dust in Early Galaxies

UT - Where Did Early Cosmic Dust Come From? New Research Says Supernovae

Universe Today

Universe Today