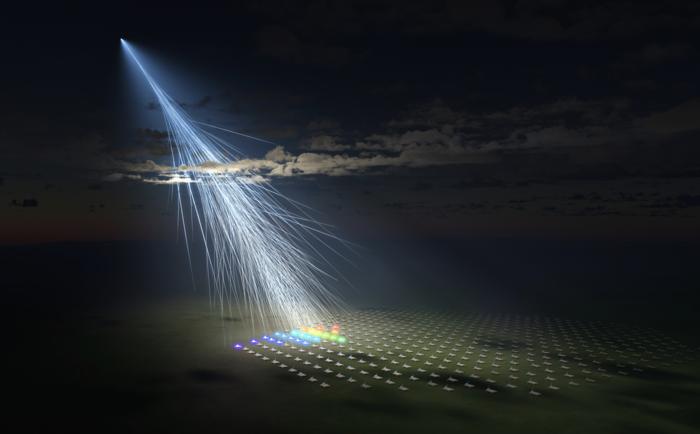

Cosmic rays, or astroparticles, are a means through which astronomers can explore the Universe. These charged particles, which are mostly protons and the nuclei of atoms stripped of their electrons, travel through space at close to the speed of light. By tracing them back to their sources, scientists can learn more about the forces that have shaped the Solar System and the Milky Way galaxy at large. When cosmic rays reach Earth, most are deflected by Earth's magnetosphere, but some manage to penetrate our atmosphere and reach the surface.

In May 2021, scientists at the international Telescope Array Project (TAP) detected one of the most energetic astroparticles ever observed, which was named the Amaterasu particle after the Japanese sun goddess. With about 40 million times the energy of particles that are smashed together in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), it was the second-highest-energy cosmic ray ever observed. Thanks to the analysis performed by Francesca Capel and Nadine Bourriche from the > Max Planck Institute for Physics (MPP), scientists are now a step closer to resolving the mystery of its origin.

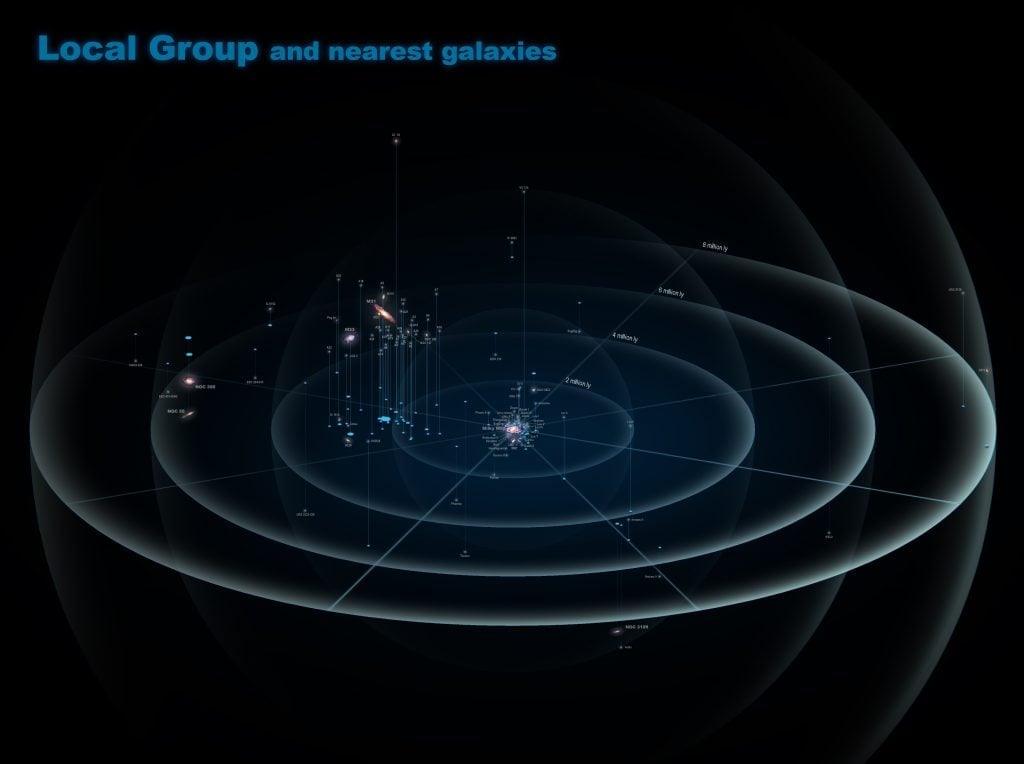

When the Amaterasu particle entered Earth's atmosphere, the TAP array in Utah recorded an energy level of more than 240 exa-electronvolts (EeV). Such particles are exceedingly rare and are thought to originate in some of the most extreme cosmic environments. At the time of its detection, scientists were not sure if it was a proton, a light atomic nucleus, or a heavy (iron) atomic nucleus. Research into its origin pointed toward the Local Void, a vast region of space adjacent to the Local Group that has few known galaxies or objects.

*The Local Group and its constituent galaxies. Credit: Antonio Ciccolella*

*The Local Group and its constituent galaxies. Credit: Antonio Ciccolella*

This posed a mystery for astronomers, as the region is largely devoid of sources capable of producing such energetic particles. Reconstructing the energy of cosmic-ray particles is already difficult, making the search for their sources using statistical models particularly challenging. Capel and Bourriche addressed this by combining advanced simulations with modern statistical methods (Approximate Bayesian Computation) to generate three-dimensional maps of cosmic-ray propagation and their interactions with magnetic fields in the Milky Way.

Their analysis suggests that the Amaterasu particle's origin may not be confined to a single empty region of the Universe and could lie within a broader range of nearby cosmic environments. One candidate their analysis suggested in particular is the nearby M82 Cigar Galaxy, located about 12 million light-years from Earth. "Our results suggest that, rather than originating in a low-density region of space like the Local Void, the Amaterasu particle is more likely to have been produced in a nearby star-forming galaxy such as M82," said Bourriche.

Their approach, which combines physics-based simulations with actual observations, is an important step toward resolving the mystery of Amaterasu's origin. It also provides a new analytical approach for tracing the sources of ultra-high-energy (UHE) cosmic rays. Furthermore, the method developed by Capel and Bourriche complements existing efforts by enabling a closer connection between theory and observations and combining information from different observations. Capel, who leads the “Astrophysical Messengers” group at the MPP, explained:

Exploring ultra-high-energy cosmic rays helps us to better understand how the Universe can accelerate matter to such energies, and also to identify environments where we can study the behavior of matter in such extreme conditions. Our goal is to develop advanced statistical analysis methods to exploit the available data to its full potential and gain a deeper understanding of the possible sources of these energetic particles.

Their findings were published in a paper, "Beyond the Local Void: A Data-driven Search for the Origins of the Amaterasu Particle," that appeared on Jan. 28th in The Astrophysical Journal.

Further Reading: MPG

Universe Today

Universe Today