We now have direct images of two supermassive black holes: M87* and Sag A*. The fact that we can capture such images is remarkable, but they might be the only black holes we can observe. That is, unless we take radio astronomy to a whole new level.

It's incredibly difficult to get high-resolution images in radio astronomy. Radio wavelengths are on the order of millimeters or larger, compared to nanometers for visible light. Since the resolution of a telescope depends on the wavelength size, radio telescopes have to be huge. It would take a radio dish nearly 10 kilometers wide to get the resolution of a large optical telescope. This is why we now build radio telescopes as arrays of smaller dishes and use interferometry to create a virtual dish the size of the array.

Both M87* and Sag A* have an apparent size of about 40 microarcseconds, which is roughly that of a baseball on the surface of the Moon. To observe such a small apparent object, astronomers had to create a virtual telescope the size of Earth. It took an array of telescopes all over the world, and even then the resolution of the Event Horizon Telescope was only about 20 microarcseconds. That's part of the reason the images are so blurry. Updates to the EHT could sharpen the resolution to 10 microarcseconds, but that's about it.

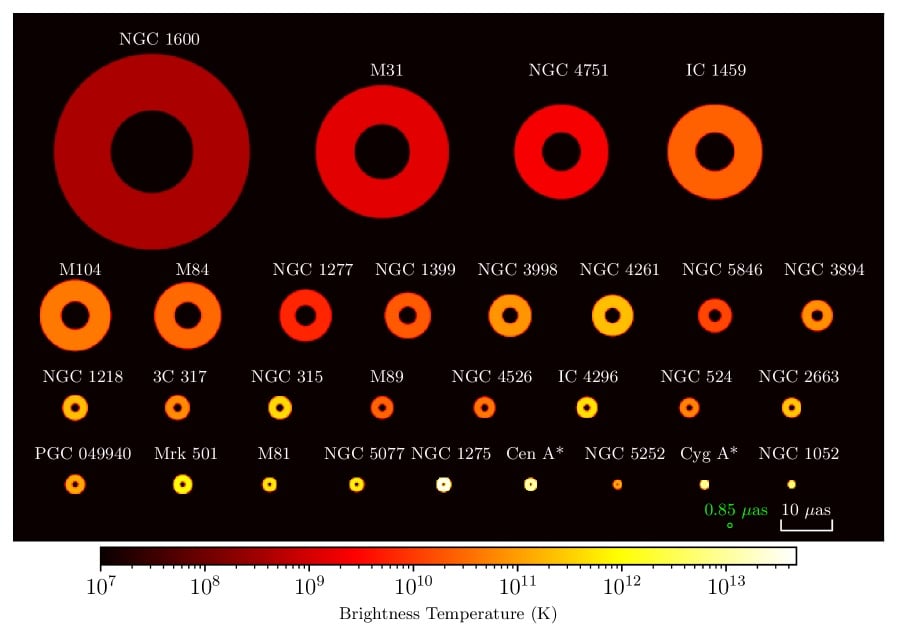

Unfortunately, M87* and Sag A* have the largest apparent size of nearby supermassive black holes. And M87* is particularly bright, making it easy to observe. While there are dozens of other black holes we'd love to observe, they are beyond the limits of the EHT. So why not make an even larger virtual telescope?

This is the idea behind a new work on the arXiv. A lunar radio telescope has been proposed many times before. Usually the idea is to locate it on the lunar far side so it will be hidden from all the radio noise from Earth. In this new work, the authors consider five possible locations: two on the far side, two on the near side, and one at the lunar south pole. Multiple locations would allow astronomers to continue observing objects as the Moon orbits the Earth and Sun.

Comparative apparent sizes and brightness of black holes that could be observed with an Earth-Moon array. Credit: Zhao, et al.

Comparative apparent sizes and brightness of black holes that could be observed with an Earth-Moon array. Credit: Zhao, et al.

The sensitivity of the proposed telescopes would depend on their overall size, but if we assume the sensitivity is similar to current Earth-based observatories, then observing other black holes comes down to the resolution of the Earth-Moon array. That depends on where the Earth and Moon are relative to their target. If the Earth and Moon are along the same line of sight, then having lunar dishes wouldn't help much. If they see the object with a baseline of the full lunar radius, then we could get resolutions less than 1 microarcsecond.

The authors look at the orientation of the Earth-Moon system relative to black holes in our greater cosmic neighborhood and find nearly 30 black holes that could be observed. These range from the supermassive black hole in the Andromeda Galaxy to Cyg A*, which is at the heart of a radio galaxy 760 light-years away.

We are decades away from operating radio telescopes on the Moon, and there are plenty of engineering challenges we have yet to solve. But studies such as this show why we should rise to that challenge. Lunar observatories would not only capture some of the faintest radio objects; they would also reveal the light around black holes in unprecedented detail.

Reference: Zhao, Shan-Shan, et al. "Beyond Sgr A* and M87*: Sub-Microarcsecond Black Hole Shadow Detection via Lunar-based Extremely Long Baseline Interferometry." *arXiv preprint* arXiv:2601.02812 (2026).

Universe Today

Universe Today