ALMA is the most powerful radiotelescope in the world, and among its many scientific endeavours is the study of protoplanetary disks around young stars. The process of planet formation is a major theme in astronomy, and with its ability to reposition its 66 radio antennae, ALMA can zoom in on dusty protoplanetary disks and spy the early indications of exoplanet formation.

In the ARKS survey (ALMA survey to Resolve exoKuiper belt Substructures), astronomers trained ALMA on debris disks in their teenage or adolescent years. It focused on disks similar to the Kuiper Belt in our Solar System. It examined the 24 most promising of these exo-Kuiper belts in order to meet two overall objectives: to analyze the detailed radial and vertical structure of these debris disks, and to characterize their gas content. ALMA's high-resolution observations can help astronomers understand the distribution of solids and gases in the disks, and their kinematics.

Exo-Kuiper belts contain the left-overs from planetary formation and are categorized as debris belts. The study of these belts has shown that our Solar System's belt is much smaller and more sparse than those around other stars. Regardless of their size, they're donut-shaped regions where icy comets and planetesimals orbit their stars.

The ARKS survey has resulted in multiple published research papers. An overview paper titled "The ALMA survey to Resolve exoKuiper belt Substructures (ARKS)" was published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. It gives an overview of the survey and its results. The lead author is Sebastian Marino from the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Exeter in the UK.

Exo-Kuiper belts are what's left after planets have finished forming. They're described as adolescent disks; they're more fully-formed and mature than very young planet-forming disks, but still haven't settled down into stable adulthood. They're also described as the missing link in the study of planet formation.

Debris disks are different than the younger protoplanetary disks where planets initially form. While the younger disks are gas-rich and bright, the teenage debris disks are dustier and dimmer. But ALMA's power has now brought these difficult to observe disks into view.

“We’ve often seen the ‘baby pictures’ of planets forming, but until now, the ‘teenage years’ have been a missing link," said Meredith Hughes, an Associate Professor of Astronomy at Wesleyan University and paper co-author in a press release.

“Debris discs are representing the collision-dominated phase of the planet formation process,” explained fellow co-author Thomas Henning, scientist at the MPIA (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy). “With ALMA, we are able to characterise the disc structures pointing to the presence of planets. In parallel, with direct imaging and radial velocity studies, we are searching for young planets in these systems.”

Planet formation ended billions of years ago in our Solar System. The Kuiper Belt preserves evidence of all of the collisions and migrations that shaped our Solar System so long ago. While ARKS is studying 24 debris disks in other systems, it's also opening a window into our Solar System's youth, as planetesimals careened into each other, the Moon was forming, and as the giant planets migrated through the system.

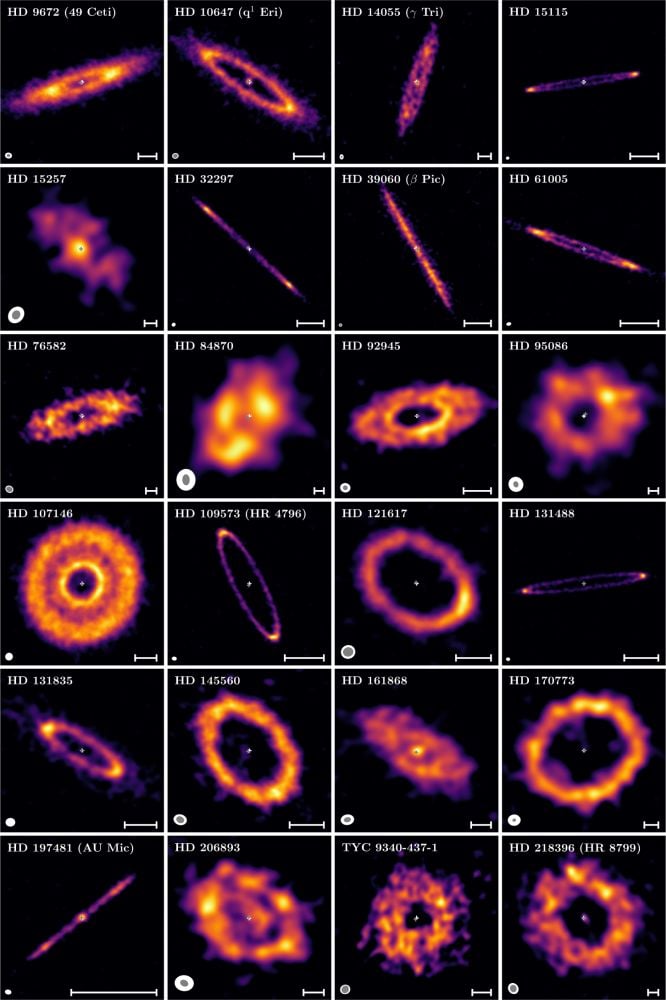

When observing exo-Kuiper belts, ALMA discovered different types of substructures. It found belts that contain multiple rings, wide smooth haloes, some sharply-defined rings, and even arcs and clumps of dusty material.

*These are the 24 debris disks from ALMA's ARKS survey. The scale bar at the bottom of each panel shows 50 au. The white crosses show the positions of the central star in each system. The disks exhibit gaps with sharp edges, some with less well-defined edges, and clumps and arcs of dusty material. Image Credit: Marino et al. 2026. A&A*

*These are the 24 debris disks from ALMA's ARKS survey. The scale bar at the bottom of each panel shows 50 au. The white crosses show the positions of the central star in each system. The disks exhibit gaps with sharp edges, some with less well-defined edges, and clumps and arcs of dusty material. Image Credit: Marino et al. 2026. A&A*

"Overall, we find that 5/24 belts have multiple rings, 7/24 belts have low-amplitude emission (either a halo or additional faint rings), and the remaining 12/24 are consistent with being single belts (some of which have substructures such as shoulders or plateaus)," the researchers explain. They write that the multiple dusty rings they observed may have been "inherited from their protoplanetary disks."

They also found that some inclined belts have non-Gaussian vertical distribution, meaning that the vertical distribution is different than a simpe bell-curve. Instead of most dust particles being in the vertical middle and their distribution tailing off both above and below the disk's middle, many of the disks exhibit greater complexity in their vertical structures.

"We also found that 10 of the 24 belts present asymmetries in the form of density enhancements, eccentricities, or warps," the researchers explain.

"We’re seeing real diversity – not just simple rings, but multi-ringed belts, halos, and strong asymmetries, revealing a dynamic and violent chapter in planetary histories,” added lead author Sebastián Marino, a program lead for ARKS, and an Associate Professor at the University of Exeter, UK.

Some of the diverse features in the disks are clues to how planets have stirred them up. Some disks exhibit both calm zones and disturbed zones, and some have puffed-up regions. This is similar to what we see in our own Kuiper Belt, where some of its occupants have been scattered by Neptune's ancient migration.

Several of the disks in ARKS also appear to have retained more gas for much longer than thought possible. This remnant gas could shape the chemical makeup of any planets that are still forming. The gas could also push the dust into even wider haloes.

Many of the disks are far from pristine in other ways. Some are tilted or lopsided, and some have eccentric shapes and arcs. These could be caused by unseen planets, they could be like scars from previous planetary migrations, or they could be caused by interaction between the gaseous disk component and the dusty component.

Just like human adolescence, a solar system's formative years are full of drama. There's a lot of transition and turmoil before a mature system eventually emerges.

This artist's illustration shows a protoplanetary disk around a young protostar. Planets form in these young, chaotic disks, and over time, everything settles down like our Solar System has. Image Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

This artist's illustration shows a protoplanetary disk around a young protostar. Planets form in these young, chaotic disks, and over time, everything settles down like our Solar System has. Image Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

“These discs record a period when planetary orbits were being scrambled and huge impacts, like the one that forged Earth’s Moon, were shaping young solar systems," says Luca Matrà, study co-author, co-PI on the ARKS survey, and Associate Professor at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland.

Overall, the 24 disks in ARKS are much more unsettled and exhibit clear differences compared to more evolved disks. "We did not expect to see such clear differences between disks around protostars and more-evolved disks,” said Nagayoshi Ohashi at Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics (ASIAA, Taiwan). Ohashi is the lead author of one of the ARKS papers. He's also part of another ALMA protoplanetary research effort, Early Planet Formation in Embedded Disks (eDisk).

John Tobin, a Co-PI of the program at the National Radio Astronomical Observatory (USA) added “Our results suggest that disks around protostars are not fully ready for planet formation. We believe that the actual formation of the planetary system progresses rapidly in the 100,000 years to 1,000,000 years after star formation begins.”

When we look around our Solar System, things are, for the most part, very calm. The occasional asteroid or interstellar object passes through the inner Solar System, and so do comets. But the planets aren't migrating, their orbits are stable, and massive collisions seem mostly confined to the past, as the cratered surfaces of the Moon and other bodies testify to.

The Moon's cratered surface is a testament to the chaos that defined the Solar System in its adolescence. The left panel shows the near side of the Moon, photographed by NASA's Galileo spacecraft. The right panel shows the lunar far side, photographed by NASA's Apollo 16 spacecraft. Image Credits: (Left) NASA/JPL/Caltech (NASA photo # PIA00405); (right) F.J. Doyle/National Space Science Data Center.

The Moon's cratered surface is a testament to the chaos that defined the Solar System in its adolescence. The left panel shows the near side of the Moon, photographed by NASA's Galileo spacecraft. The right panel shows the lunar far side, photographed by NASA's Apollo 16 spacecraft. Image Credits: (Left) NASA/JPL/Caltech (NASA photo # PIA00405); (right) F.J. Doyle/National Space Science Data Center.

But it wasn't always this way, and ARKS and ALMA are showing us what our young Solar System was like.

“This project gives us a new lens for interpreting the craters on the Moon, the dynamics of the Kuiper Belt, and the growth of planets big and small. It’s like adding the missing pages to the Solar System’s family album,” said co-author Hughes from Wesleyan.

Though ALMA has made significant headway studying planet formation in other Solar Systems, there are some important questions still waiting for answers.

"Perhaps the most important question that is yet to be answered is whether any or most of the observed structures are linked to the presence of planets in these systems," the authors write.

"Some of these systems host planets, but most reside far from the edges of these belts. The James Webb Space Telescope and soon the Extremely Large Telescope may reveal or rule out the presence of planets actively shaping these discs," the authors conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today