For its first three billion years, Earth barely resembled the modern Earth, at least atmospherically. There was no free oxygen, and the atmosphere was dominated by nitrogen, as it is today. There was far more carbon dioxide, maybe even 100 times as much. There was also water vapour, and trace amounts of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and other gases. There was also more significant amounts of methane.

The methane is critical, since it explains so much about life on Earth at the time. The methane was produced by some of Earth's first life forms, called methanogens. Methane is a byproduct of how these early life forms generated their energy in the oxygen-free atmosphere.

This all changed during the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE). The GOE began about 2.4 billion years ago, when a new type of life appeared. These new microbes, called cyanobacteria, used photosynthesis to produce energy, and their byproduct wasn't methane, but oxygen. It took hundreds of millions of years of work by cyanobacteria, but eventually free oxygen gathered in the atmosphere.

This led to complex life. When oxygen appeared in the atmosphere, it allowed lifeforms to harness far more energy. The greater energy yield from respiration is considered a major factor in the evolution of complex, multicellular life.

But new research shows that the GOE couldn't have happened without the rapid appearance of another critical element: phosphorus. The research is titled "Marine phosphorus and atmospheric oxygen were coupled during the Great Oxidation Event," and it's published in Nature Communications. The lead author is Dr. Matthew Dodd, from the University of Western Australia's School of Earth and Oceans.

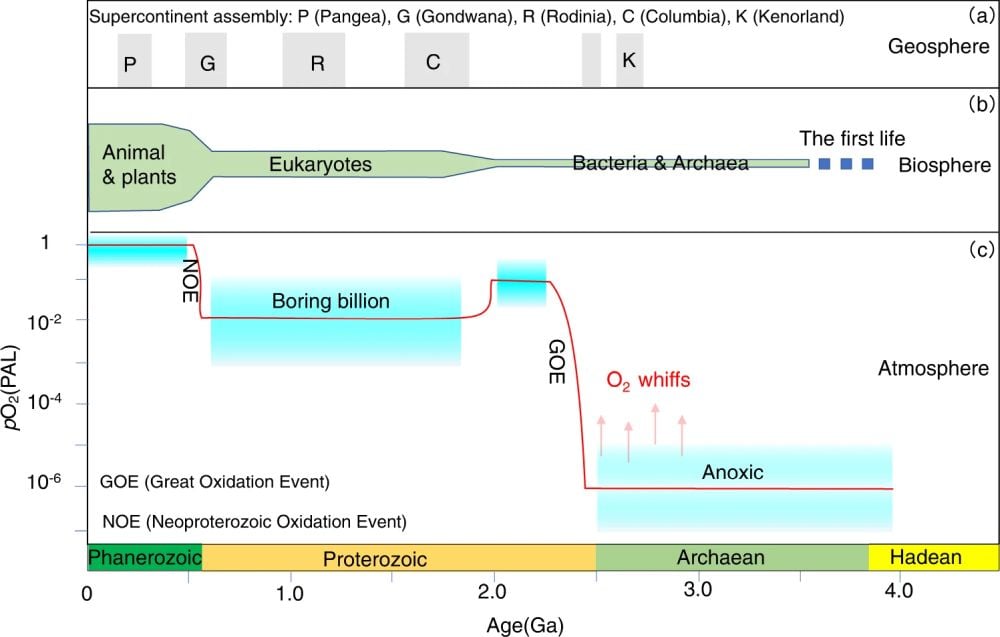

This timeline image shows the evolution of the geosphere (continents), the biosphere, and the atmosphere. Scientists know that the GOE was not a simple, linear event as depicted here. There were multiple fluctuations during the GOE in different parts of the oceans. Image Credit: Chen et al. 2022. NatComm.

This timeline image shows the evolution of the geosphere (continents), the biosphere, and the atmosphere. Scientists know that the GOE was not a simple, linear event as depicted here. There were multiple fluctuations during the GOE in different parts of the oceans. Image Credit: Chen et al. 2022. NatComm.

Many things are touted as being critical for life. Carbon is one, and Earth life is called carbon-based life because of it. In fact, all of the organic chemicals in CHNOPS—carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur—are necessary for life. But this new research points out the critical role phosphorus played in the GOE and the appearance of complex life.

Earth has abundant phosphorus. It's the 11th most abundant element in the crust. It's also abundant in living things and is the backbone of DNA. But despite its abundance, it's also limited.

Up to 99% of the Earth's phosphorus is locked up in Earth's core because it's so soluble in metals. That phosphorus will never be available for life.

The new research shows that there was enough available phosphorus for it to surge into the oceans periodically. The phosphorus triggered subsequent blooms in photosynthetic microbes, which in turn created more free oxygen in the atmosphere during the GOE.

“By fuelling blooms of photosynthetic microbes, these phosphorus pulses boosted organic carbon burial and allowed oxygen to accumulate in the air, a turning point that ultimately made complex life possible,” Dodd said in a press release.

As a vital organic element, phosphorus acts as a throttle on biological activity. More phosphorus means more biological activity; less phosphorous means less biological activity. To measure phosphorus levels in ancient oceans, researchers have to do some sleuthing.

*The GOE was a complex, multilayered event that played out over time and highlighted the links between geology and continental activity, life, and atmospheric and ocean chemistry. Banded iron formations are some of the strongest evidence supporting the GOE. They're alternating layers of iron oxides and iron-poor chert. They formed in seawater as a result of oxygen produced by photosynthetic bacteria. Image Credit: By Graeme Churchard from Bristol, UK - Dales GorgeUploaded by PDTillman, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30889569*

*The GOE was a complex, multilayered event that played out over time and highlighted the links between geology and continental activity, life, and atmospheric and ocean chemistry. Banded iron formations are some of the strongest evidence supporting the GOE. They're alternating layers of iron oxides and iron-poor chert. They formed in seawater as a result of oxygen produced by photosynthetic bacteria. Image Credit: By Graeme Churchard from Bristol, UK - Dales GorgeUploaded by PDTillman, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30889569*

The research is based on ancient carbonate rocks. Carbonate rocks are sedimentary rocks that usually form in marine environments. Limestone and dolomite are the two most common types. Carbonate rocks provide important data in the study of paleoclimatology.

"Carbonate minerals incorporate elements into their crystal structure proportionally to the elemental concentrations in the seawater," the authors explain. "Based on this premise, it is possible to estimate ancient marine P concentrations using the concentration of phosphate in carbonate minerals when factoring in ambient seawater chemistry (e.g. pH, alkalinity and temperature) and mineralogy, which also play a role in the uptake of elements by carbonate minerals."

In this work, the researchers focused on carbonate-associated phosphate (CAP), a proxy for ocean phosphate levels that researchers use to reconstruct those levels in Earth's ancient oceans. They found that CAP tracks carbon isotope signatures that record biological activity and the sequestering of carbon into rock.

Dodd and his colleagues ran thousands of simulations. They showed that when there were transient increases in the available phosphorus in the ocean, it generated rapid oxygenation along with isotopic carbon fingerprints in rock.

"Here we use the carbonate-associated phosphate (CAP) proxy to reconstruct oceanic phosphorus concentrations during the GOE from globally distributed sedimentary rocks," the authors write in their research. "We find that the CAP and the inorganic carbon isotope composition of marine sediments co-varied during the GOE, suggesting synchronous fluctuations in marine phosphorus, biological productivity, and atmospheric O₂."

The phosphorus caused photosynthetic life to bloom in the oceans, generating more oxygen in the atmosphere. And as more carbon was sequestered in rock, that created even more free oxygen.

The obvious question is 'Where did the phosphorus come from?'

Phosphate was present in the ancient oceans but chemically unavailable. In the Precambrian oceans, iron scavenged phosphate and locked it away. There was also limited sulphate availability, and sulphate aids efficient recycling of organic-bound phosphorus. But the research showed that for at least part of the GOE, these limitations were relaxed. This opened the throttle on available phosphorus, fostering the buildup of free oxygen in the atmosphere.

“Oxygen is the hard currency of complex life and when phosphorus levels rose in the early oceans, photosynthesis revved up,” said Dodd. “When more organic carbon was buried it resulted in oxygen being free to build in the atmosphere and that’s how Earth took its first big breath.”

Studying Earth's detailed history can also aid the study of exoplanets and potential biosignatures. For strong reasons, astrobiologists focus on oxygen as a biosignature. On Earth, atmospheric oxygen rose as life generated it.

But oxygen can also be created abiotially, and this work points to phosphorus as a potential biosignature due to its throttling effect on biological activity.

“Astronomers increasingly treat oxygen-rich atmospheres as prime targets in the search for life beyond Earth, but oxygen can, in principle, arise without biology,” Dodd said. “By identifying a nutrient throttle that couples oceans, biology and the atmosphere, we offer a testable, biological pathway for creating and sustaining oxygen on living worlds."

“We also provide a framework for interpreting oxygen detections on planets outside our solar system,” Dodd concluded.

Universe Today

Universe Today