Most evidence shows that supermassive black holes (SMBH) sit in the center of massive galaxies like ours. Their masses can be extraordinary; many billions of times more massive than the Sun. All that concentrated mass has a powerful effect on their surroundings.

SMBH have multiple far-reaching effects: Their mass governs the orbits of billions of stars; when they're active they can emit intense jets of powerful radiation that extend for millions of light-years; and their energetic output limits star formation. And when an indivdual stars gets to close to an SMBH, they're torn apart in tidal disruption events.

In short, the region near an SMBH is a chaotic sea of turbulent gas driven to extremes by the black hole's energy. Even though astrophysicists know this, and even though they know all of this turbulence must affect star formation and the evolution of the galaxy an SMBH sits in, unanswered questions are abundant. Two new papers use data from the JAXA/NASA/ESA x-ray space telescope XRISM (X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission) to illuminate the intense regions around SMBH.

The first paper is "Disentangling multiple gas kinematic drivers in the Perseus galaxy cluster," and it's published in Nature. The XRISM collaboration is credited as the overall author.

The second paper is "A XRISM/Resolve view of the dynamics in the hot gaseous atmosphere of M87," and will be published in The Astrophysical Journal. The primary author is Hannah McCall, a graduate student at the University of Chicago.

“For the first time, we can directly measure the kinetic energy of the gas stirred by the black hole,” said Annie Heinrich, a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Heinrich is one of the lead authors on the paper in Nature. “It’s as though each supermassive black hole sits in the ‘eye of its own storm.’”

XRISM was launched in 2023 to study AGN feedback and related phenomena. It carries two instruments, each with its own telescope: Resolve, and Xtend. Compared to its predecessor Hitomi, which was lost after only about five weeks of operation, XRISM is more perceptive. Critically, XRISM can distinguish between x-rays from different elements and different ionization states. And it does so with outstanding precision.

“XRISM allows us to unambiguously distinguish gas motions powered by the black hole from those driven by other cosmic processes, which has previously been impossible to do,” said Congyao Zhang, who co-led the Nature research. Zhang is a former UChicago postdoctoral researcher, currently at Masaryk University in Czechia.

It's been impossible because SMBH are chaotic and messy. When they're feeding—or actively accreting—gas and dust are drawn toward them. The material gathers into an accretion ring that rotates around the SMBH. Some material from the ring does fall into the black hole, but not all of it. Some of it is emitted in powerful jets. These streams of highly-energetic particles reach relativistic speeds. The amount of energy a SMBH injects into its surroundings is almost unimaginable. All that energy influences the black holes's surroundings up to hundreds of thousands of light-years away.

Astronomers have observed this environment before and know this is how black hole feedback shapes galaxies and regulates star formation. But no previous observations were as detailed as XRISM's. These new observations see more deeply into the murky arena of black hole feedback than any previous efforts.

When a black hole's energetic output strikes gas in the black hole's surroundings, each element emits slightly different x-ray light. XRISM has the ability to see these differences in great detail. As a result, it can also trace the movement of different gases, and their velocities.

“Before XRISM, it was like we could see a picture of the storm,” said Heinrich. “Now we can measure the speed of the cyclone.”

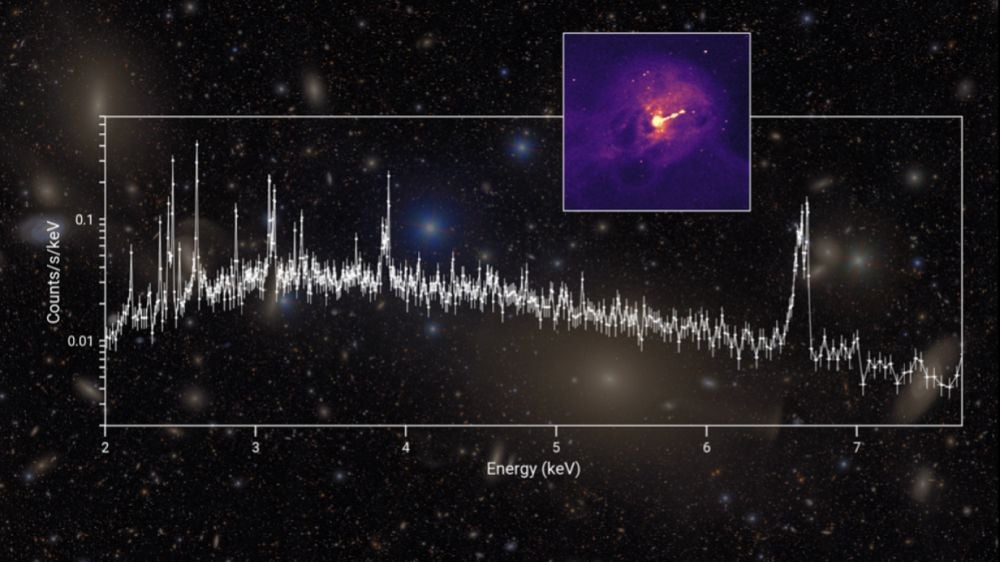

This image shows a XRISM x-ray spectrum from the hot gas near M87 in the Virgo Cluster (inset image). Each spike represents a different element present in the gas. The shapes and positions of each spike also reveal how fast the heated gas is moving. The background image is from the Rubin Observatory and shows individual galaxies in the Virgo Cluster. Image Credit: Rubin Observatory (optical), Chandra (x-ray inset), and XRISM (x-ray spectrum).

This image shows a XRISM x-ray spectrum from the hot gas near M87 in the Virgo Cluster (inset image). Each spike represents a different element present in the gas. The shapes and positions of each spike also reveal how fast the heated gas is moving. The background image is from the Rubin Observatory and shows individual galaxies in the Virgo Cluster. Image Credit: Rubin Observatory (optical), Chandra (x-ray inset), and XRISM (x-ray spectrum).

In one of the studies, XRISM zoomed-in on the galaxy M87, at the heart of the Virgo Cluster. It's about 53 million light-years away, which is close for a galaxy. M87 has a supermassive black hole that's also referred to as M87. XRISM's observations showed powerful turbulence near the SMBH, the strongest ever measured. But XRISM also showed something else.

“The velocities are high closest to the black hole, and drop off very quickly further away,” said Hannah McCall, primary author on the paper analyzing the Virgo Cluster. “The fastest motions are likely due to a combination of eddies of turbulence and a shockwave of outflowing gas, both a product of the black hole.”

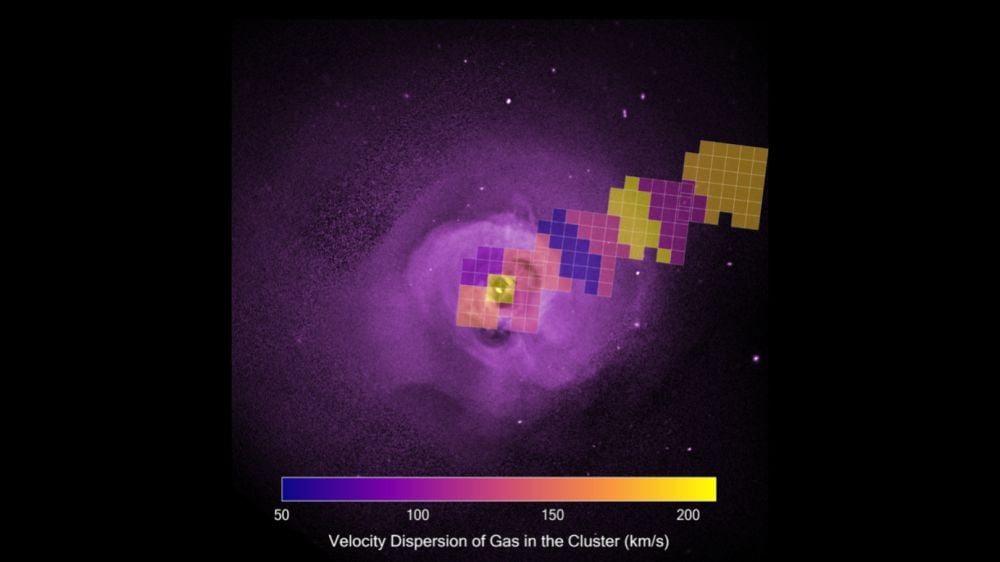

The Perseus Cluster is the target of the other paper. It's about 240 million light-years away and is the brightest x-ray cluster from Earth. Its high luminosity let researchers measure the motion of the gas in the cluster's center and beyond. They found gas moving at different scales and separate velocities. One is from the black hole itself and is on a smaller scale, while the other is on a large scale and comes from an ongoing merger between Perseus and other galaxies.

*This image shows XRISM x-ray data from the Perseus Cluster. The panels shows the regions where XRISM measured gas velocity, with yellow being the fastest and blue being the slowest. The velocity is highest near the center, where the SMBH is. The larger-scale gas is driven by an ongoing merger. Image Credit: JAXA*

*This image shows XRISM x-ray data from the Perseus Cluster. The panels shows the regions where XRISM measured gas velocity, with yellow being the fastest and blue being the slowest. The velocity is highest near the center, where the SMBH is. The larger-scale gas is driven by an ongoing merger. Image Credit: JAXA*

These detailed observations address an ongoing issue in astronomy. We know that stars form from cold gas, and that anything that heats gas inhibits star formation. Since SMBH can heat up surrounding gas, their feedback slows star formation. But seeing the motion of the gas reveals more detail.

Astronomers have wondered why they see fewer stars in the centers of galaxy clusters than they expect. While central AGN can heat up some gas, the turbulent motion of the gas further beyond the SMBH can also heat gas. Depending on how much of its motion is converted into heat, it could counteract the natural cooling of gas in the intracluster medium, and the subsequent star formation.

“It remains an open question whether this is the only heating process at work, but the results make it clear that turbulence is a necessary component of the energy exchange between supermassive black holes and their environments,” said McCall.

There's so much we don't know. Even though we can talk relatively casually and with confidence about aspects of SMBH that we do understand, it's a classic iceberg situation. There's so much we don't know, we can't really understand exactly how confident we should be about what we think we do know.

SMBH are gargantuans that warp spacetime and spread their effects out for hundreds of thousands of light-years. One aspect of their existence is grounded in this side of their event horizons. Their other aspect, beyond the event horizon, is completely unknown. We may never crack that mystery.

But astronomers and astrophysicists can observe them in increasingly deeper detail, thanks to XRISM and other instruments. They can study how SMBHs affect their surroundings on this side of the event horizon more deeply. The specifics of how SMBH affect star formation and galactic evolution is a layered puzzle waiting to be solved.

There are some uncertainties in the measurements and observations, which is expected. But the main conclusion is unaffected. "Regardless of the uncertainties, our main conclusion - that at least two sources on very different scales drive gas motions within the Perseus core - remains robust, thanks to the XRISM’s radial mapping observations with high spectral resolution," the authors of the first paper explain.

The authors of the second paper reach a similar conclusion. "The peaked central velocity dispersion corresponds spatially with known AGN-driven structures, suggesting that AGN feedback is the primary source of motions in this region," they write. Future XRISM observations of M87's arms will reveal more detail, and a future mission will dig even deeper.

"In the longer term, ESA’s upcoming New Athena mission, with its superior spectral and spatial resolution, will be instrumental in resolving the small-scale velocity structure and mapping turbulence across the ICM, building on the insights into AGN feedback in cluster environments provided by XRISM," they conclude.

“Based on what we’ve already learned, I am positive we are getting closer to solving some of these puzzles,” said Irina Zhuravleva, associate professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UChicago and a co-author of both studies.

Universe Today

Universe Today