The Moon has a long history of being smacked by large rocks. Its pock-marked, cratered surface is evidence of that. Scientists expect that, as part of those impacts, some debris would be scattered into space - and that we should be able to track it down. But so far, there have been startlingly few discoveries of these Lunar-origin Asteroids (LOAs) despite their theoretical abundance. A new paper from Yixuan Wu and their colleagues at Tsinghua University explains why - and how the Vera Rubin Observatory might help with finding them.

Saying the discoveries are “rare” isn’t the same as saying they’re non-existent. The media picked up on the story of our “temporary Moon” - asteroid 2024 PT5 - at the end of 2024, and it appears to be of lunar origin. Another LOA, known as Kamo’oalewa, is the target of a future Chinese asteroid sample return mission. But according to calculations from the paper, there should be 500,000 more of them sized around 5 meters in diameter, hiding somewhere near cislunar space.

Granted, that is still only about 1% of the population of Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs) in that size range. The vast majority of NEAs originate in the asteroid belt and are pushed into the inner solar system either by gravity or impact with their neighbors. Perhaps the most interesting insight from the paper was how to differentiate between lunar-origin asteroids and those from the asteroid belt, without having to collect expensive spectral data on every single one of them. It has to do with velocity and direction.

Anton Petrov discusses the one of the most famous LOAs - Kamo’oalewa. Credit - Anton Petrov YouTube ChannelA typical LOA has a velocity relative to Earth of around 12.8 km/s, whereas other types of NEAs have an average velocity of 17.5 km/s. It’s still not a fool-proof assessment, though - even at speeds as low as 2.4 km/sec, there’s still only a 30% chance that the asteroid is a LOA - though that’s more than 30x higher chance of it being an LOA than just any random asteroid. The other notable characteristic of LOAs is their direction - they approach Earth either from the sunward or anti-sunward direction, avoiding the leading and trailing edge of Earth’s orbital path.

Those findings were the results of a model the researchers ran to try to study how LOAs are formed, and what happened to them over the course of their lifetime in space. So they modeled the history of the Moon being smashed by asteroids itself, and then tracked particles ejected into space from those impacts over the course of 100 million years. In fact, they ran two different simulations - one of which assumed an average of impacts over time, whereas the other concentrated specifically on the impact that caused the Giordano Bruno crater, which formed around 4 million years ago. Also importantly, the model included the Yarkovsky effect, which is a tiny force exerted on asteroids by the reflection of sunlight that essentially makes them very inefficient solar sails, but over millions of years can have a very large impact on their orbital mechanics.

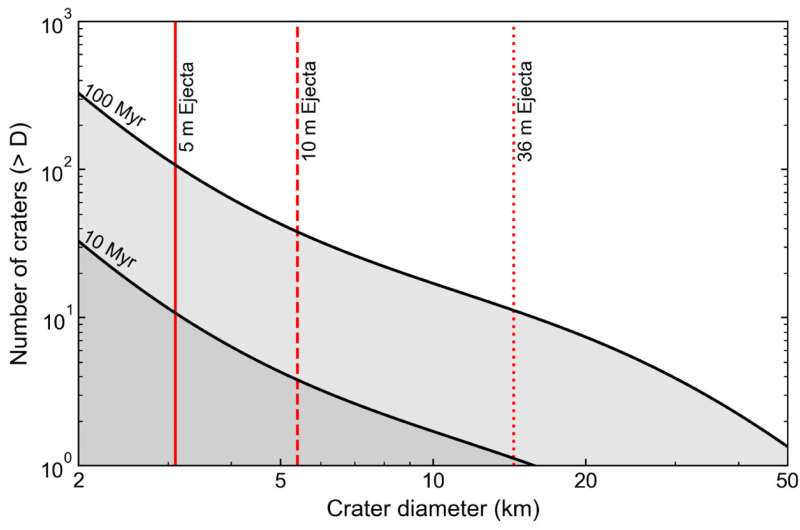

Unsurprisingly, most of the ejecta from these impact events didn’t survive the 100 million year timeline. Around 25% fell down to Earth in the first 100,000 years, to become lunar meteorites. After the full simulation time was run, only 1.6% of the ejecta remained in near Earth space, with the rest landing on Earth, back on the Moon, or being flung out into the wider solar system. But even with that low survival percentage, it should still be enough to make the 500,000 LOAs that the researchers think might be out there.

YouTube video showcasing the potential discovery of the Vera Rubin Observatory. Credit - Jake Andrew Kurlander YouTube ChannelTherefore, the next challenge is finding them. Existing surveys, like Pan-STARRS and ATLAS aren’t particularly good at finding these low-magnitude, fast-moving objects. However, the upcoming Vera Rubin observatory in Chile is expected to find around 6 a year - an order of magnitude improvement over existing surveys. But still only a drop in the bucket compared to the hundreds of thousands that likely exist.

Researchers have to start somewhere though, and this is as good a place as any to begin studying these relatively rare members of our cis-lunar neighborhood. Doing so should help us better understand the impact history of our nearest neighbor. But it might also help us understand the impacts such rocks could have on our own planet.

Learn More:

Tsinghua University / Phys.org - As Rubin's survey gets underway, simulations suggest it could find about six lunar-origin asteroids per year

Y. Wu et al. - Detectability of Lunar-origin Asteroids in the LSST Era

UT - A New Study of Lunar Rocks Suggests Earth's Water Might Not Have Come from Meteorites

UT - Asteroid 2024 YR4 Has a 4% Chance of Hitting the Moon. Here’s Why That’s a Scientific Goldmine.

Universe Today

Universe Today