The thunderous roar that echoed across Huntsville, Alabama, on January 10 wasn't a rocket launch but something equally momentous: the end of an era. Two massive test stands that helped send humans to the Moon collapsed in carefully choreographed implosions, their steel frameworks crumbling in seconds after decades standing as monuments to American spaceflight achievement.

Apollo's Saturn V rocket powers off the launchpad (Credit : NASA)

Apollo's Saturn V rocket powers off the launchpad (Credit : NASA)

The Dynamic Test Stand and the Propulsion and Structural Test Facility, better known as the T-tower for its distinctive shape, represented more than just obsolete infrastructure. Built in the 1950s and 60s, these structures witnessed the birth of the space age, serving as proving grounds where engineers pushed the limits of rocket technology and ensured every component could withstand the violence of launch.

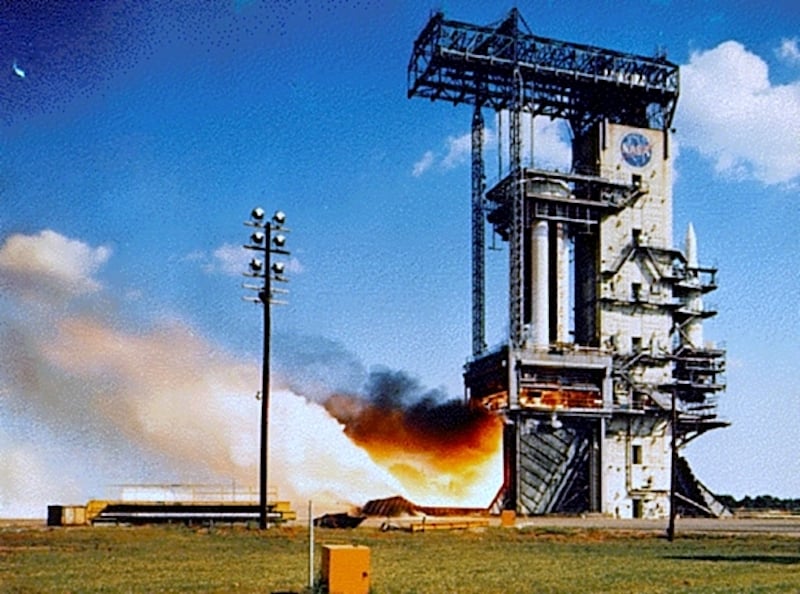

The T-tower came first, constructed in 1957 by the Army Ballistic Missile Agency before NASA even existed. At just over 50 metres tall, it was designed for static testing, where rockets are fired at full power while restrained and connected to instruments that measure every vibration, temperature spike, and pressure fluctuation. Here, engineers tested components of the Saturn family of launch vehicles under the direction of Wernher von Braun, including the mighty F-1 engines that would eventually power Apollo missions. The tower later proved essential for testing Space Shuttle solid rocket boosters before being retired in the 1990s.

The Dynamic Test Stand told an even more dramatic story. Built in 1964 and rising over 105 metres above the Alabama landscape, it once stood as the tallest human made structure in North Alabama. Unlike the T-tower's static tests, this facility subjected fully assembled Saturn V rockets to the mechanical stresses and vibrations they would experience during actual flight, everything shaking, flexing, and straining just as it would during launch, but without leaving the ground. Engineers couldn't afford failures once these rockets reached the launchpad at Kennedy Space Centre, Saturn V was too powerful, too expensive, and too important to risk.

The Propulsion and Structural Test Facility at the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville (Credit : Marshall Space Flight Center History Office)

The Propulsion and Structural Test Facility at the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville (Credit : Marshall Space Flight Center History Office)

The stand's role didn't end with Apollo. In 1978, it became the first location where engineers integrated all Space Shuttle elements together; orbiter, external fuel tank, and solid rocket boosters assembled as one complete system. Its final mission came in the early 2000s, when it served as a drop tower for microgravity experiments, a far quieter purpose than its explosive origins.

Both facilities earned designation as National Historic Landmarks in 1985, recognition of their irreplaceable contributions to human spaceflight. That makes their demolition bittersweet but necessary. The structures are no longer safe, and maintaining aging facilities drains resources that could support current missions. Marshall is removing 19 obsolete structures as part of a broader campus transformation, creating a modern, interconnected facility ready for NASA's next chapter.

"These facilities helped NASA make history. While it is hard to let them go, they've earned their retirement. The people who built and managed these facilities and empowered our mission of space exploration are the most important part of their legacy." - Acting Marshall centre director Rae Ann Meyer.

NASA has worked to preserve that legacy. Detailed architectural drawings, photographs, and written histories now reside permanently in the Library of Congress. Auburn University created high resolution digital models using LiDAR and 360 degree photography, capturing the structures in exquisite detail before their destruction. These virtual archives ensure future generations can still appreciate the scale and engineering achievement these towers represented, even after the steel has been cleared away.

Universe Today

Universe Today