Intermediate mass black holes (IMBH), if they exist, have between about 100 and 1000 solar masses, placing them in between stellar black holes and supermassive black holes. But while there's plenty of evidence for both stellar mass black holes and supermassive black holes, the evidence for IMBHs isn't as convincing. There are many candidates, but there's no wide agreement on any of them. Yet our theories of black holes show there should be something in between stellar black holes and supermassive black holes, and IMBHs could be the missing link.

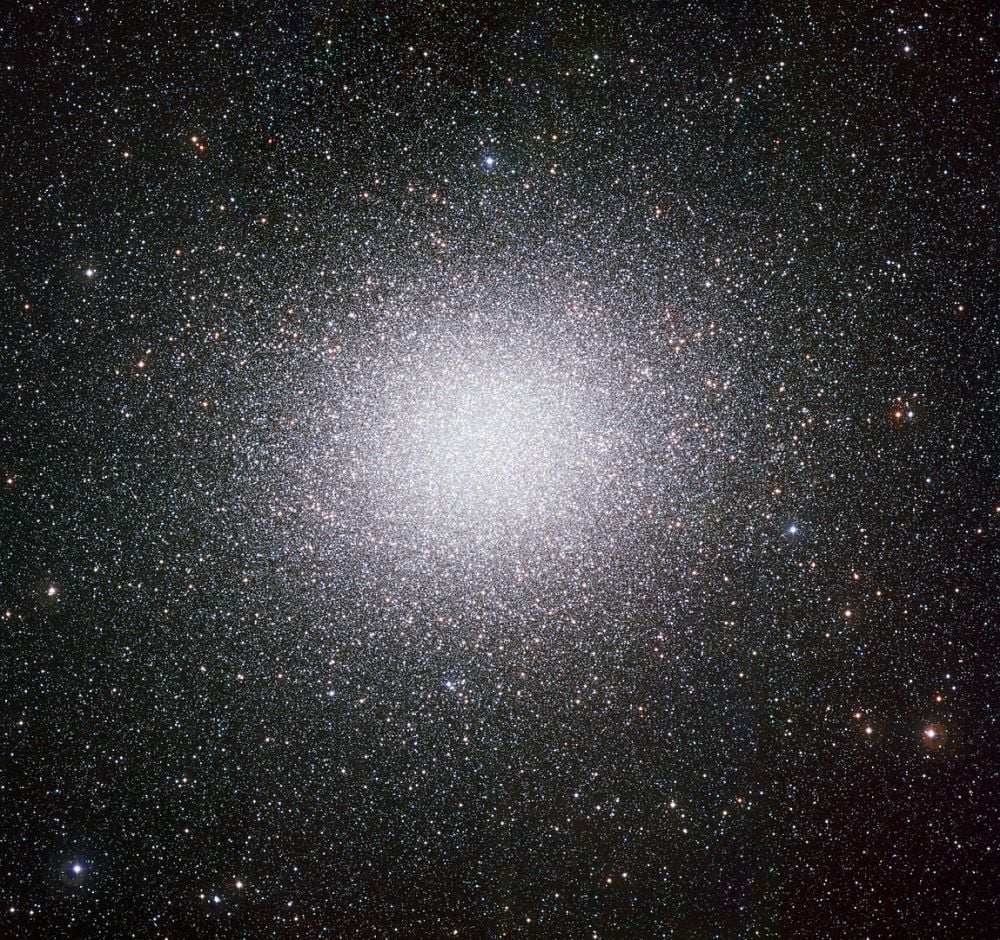

The most well-known IMBH candidate is in the globular cluster Omega Centauri. OC is about 17,000 light-years away and has been known since antiquity, when astronomers thought it was a single star. Now we know that it hosts roughly 10 million stars, and our powerful telescopes have resolved thousands of individual stars in the tighly-packed cluster. Astronomers think OC might be what's left of a dwarf galaxy that was disrupted by the Milky Way. What we're seeing now could be the remnant core from that galaxy.

But black holes can't be seen. Their presence can be inferred by the effect their massive gravity has on their surroundings. We know that the Milky Way hosts a supermassive black hole because of the behaviour of the stars nearby. The same might be true for Omega Centauri.

A 2024 paper found seven stars in the center of Omega Centauri that are moving very quickly. Their velocity is greater than the escape velocity, so something's keeping them there. The most obvious conclusion is that an IMBH has a grip on them.

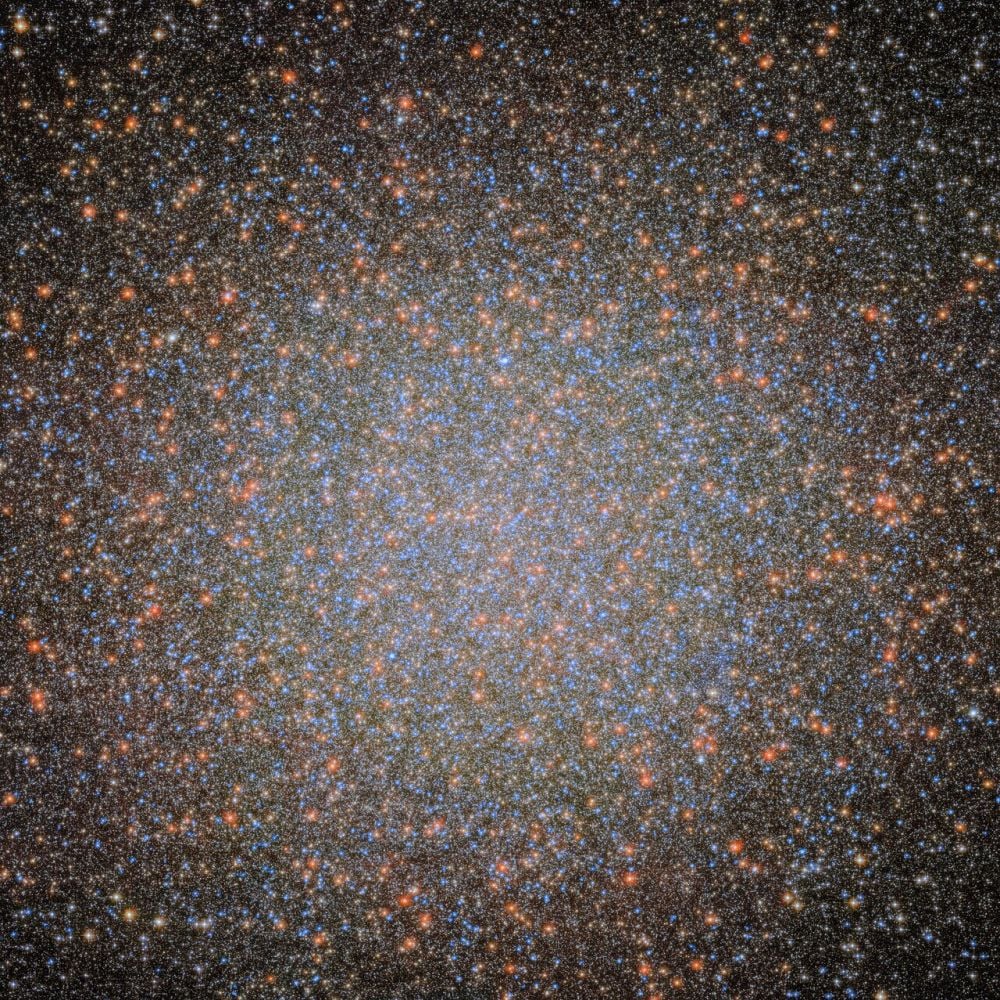

In 2024, a team of astronomers used more than 500 Hubble image of Omega Centauri to measure the velocities of 1.4 million stars in the cluster. Seven of them are moving so quickly that they've exceeded escape velocity, yet they're still bound to the cluster. That's compelling evidence that an IMBH is in Omega Centauri's center. Image Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, M. Häberle (MPIA)

In 2024, a team of astronomers used more than 500 Hubble image of Omega Centauri to measure the velocities of 1.4 million stars in the cluster. Seven of them are moving so quickly that they've exceeded escape velocity, yet they're still bound to the cluster. That's compelling evidence that an IMBH is in Omega Centauri's center. Image Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, M. Häberle (MPIA)

Black holes are known for accreting matter, and new research used the JWST to probe Omega Centauri, searching for evidence of accretion. That evidence would bolster the idea that Omega Centauri hosts an IMBH. The research is titled "The Intermediate Mass Black Hole in Omega Centauri: Constraints on Accretion from JWST," and it's been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal. It's available at arxiv.org, and the lead author is Steven Chen from the Department of Physics at The George Washington University in Washington DC.

"Searches for IMBHs in GCs can involve direct detection of emission from the IMBH, or the indirect observation of the impact of the IMBH on GC dynamics," the authors write. Black holes emit radiation as they accrete matter, and those emissions should be detectable. Previous research has examined Omega Centauri in radio and x-rays for signs of emissions and was able to constrain mass estimates for the purported IMBH.

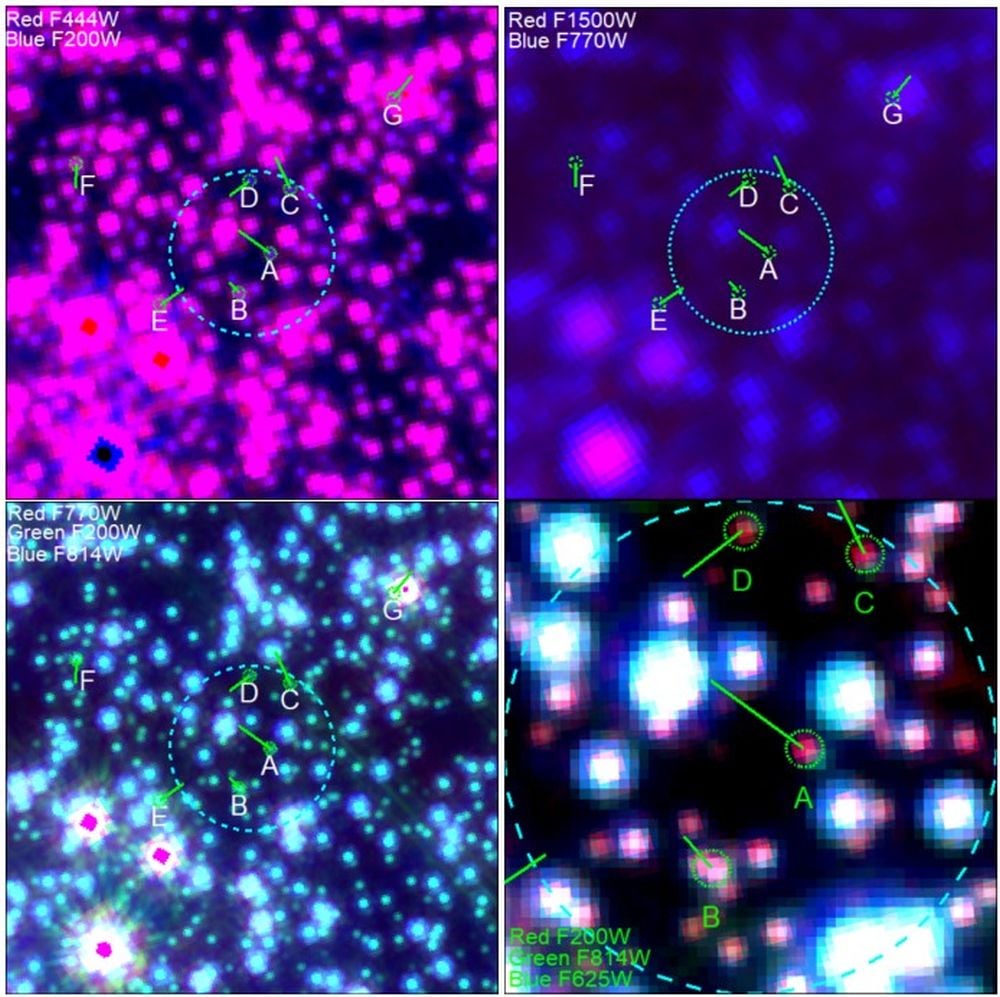

The JWST observed Omega Centauri in 2024 with its MIRI and NIRCam instruments, and this research is based on the data from those observations.

These images from the research show 4 of the JWST's views of Omega Centauri's central region of interest. The seven fast-moving stars are labelled A through G. The researchers found no evidence to suggest that any source in the Region of Interest is an isolated IMBH. Image Credit: Chen et al. 2025.

These images from the research show 4 of the JWST's views of Omega Centauri's central region of interest. The seven fast-moving stars are labelled A through G. The researchers found no evidence to suggest that any source in the Region of Interest is an isolated IMBH. Image Credit: Chen et al. 2025.

Previous research placed constraints on the mass of the IMBH in Omega. The motions of the fast stars in the cluster indicated a plausible mass range of 39,000 to 47,000 solar masses, with an extreme lower limit of 8,200 solar masses.

These new JWST observations can't say decisively whether there's an IMBH in Omega. They can only place further constraints on its mass, based on electromagnetic emissions and what scientists know about accretion efficiency. The JWST excluded the lower 8,200 solar mass limit from previous research, and suggests a mass of about 20,000 solar masses.

Observing the center of Omega Centauri and trying to discern the presence of an IMBH based on infrared data is very difficult. The region is choked with stars, and what appears to be a single point source could be two or more stars in proximity to one another. There may be tens of thousands of stars per cubic light-year, and OC is 17,000 light-years away.

"In conclusion, despite the unprecedented depth and resolution that JWST offers, searching for IMBH signals in very crowded environments remains challenging," the authors write. "Flux limits in Omega Centauri strongly depend on proximity to stars, while limits on the IMBH mass also depend on the accretion model and assumptions about the mass accretion rate."

But placing ever-tightening constraints on objects is a critical part of scientific progress. By constraining the mass of a potential IMBH in Omega Centauri, these authors are taking the next steps toward possibly confirming that these elusive, missing-link black holes exist.

The JWST's powerful infrared observing capabilities will continue to be a part of the search for an IMBH in Omega. "Nevertheless, future JWST observations can further improve proper motion measurements of stars obtained from 20 years of HST observations," the authors write, pointing out that the depth of its images should uncover new fast stars in the vicinity that are too faint for other telescopes to see.

But these results show that if an IMBH is there, it's not emitting much radiation, and, hence, not accreting matter very quickly. "If these future proper motion measurements further substantiate the existence of an IMBH in Omega Cen, limits on its emission can be used to refine models of BH emission in low accretion rate regimes," the authors conclude.

It looks like we'll have to wait a while before there's a convincing "Eureka!" moment. But as research like this shows, it may come down to a process of elimination, until the only plausible explanation is an IMBH.

Universe Today

Universe Today