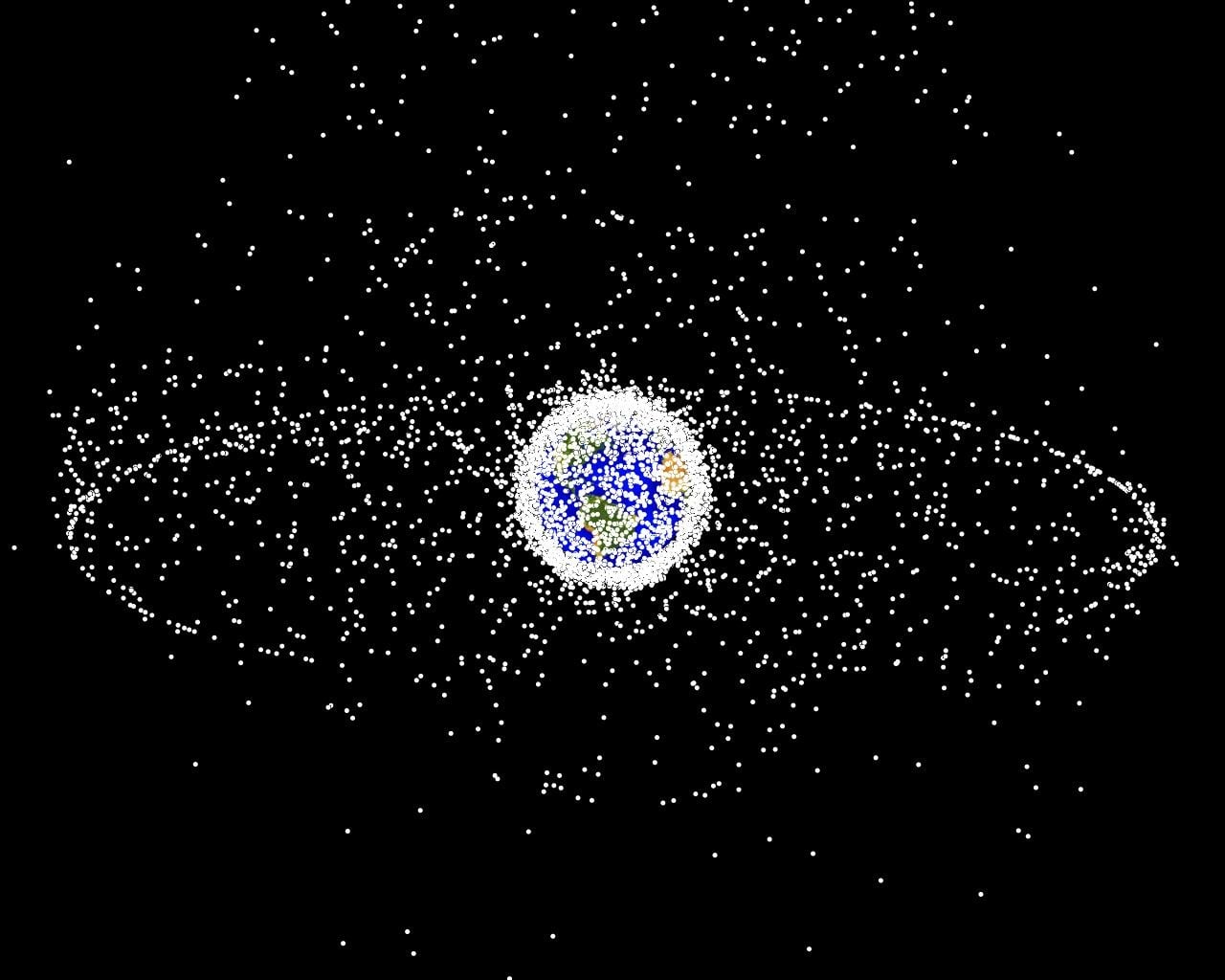

Space debris encompasses thousands of defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, and fragments from collisions or explosions that orbit Earth at speeds exceeding 27,000 kilometres per hour. This growing population of human made junk poses collision risks to operational spacecraft and, when gravity eventually pulls larger pieces down through the atmosphere, can threaten people on the ground with falling fragments that sometimes survive reentry intact.

Space debris doesn't fall quietly though. When a defunct satellite or spent rocket stage plummets through Earth's atmosphere at hypersonic speeds, it produces thunderous sonic booms that rumble the ground below. Benjamin Fernando at Johns Hopkins University realised this offered an unexpected opportunity. He suggested the same networks of seismometers designed to detect earthquakes could track falling space junk by listening for those distinctive shockwaves.

Computer generated image of space debris objects in Earth orbit (Credit : NASA)

Computer generated image of space debris objects in Earth orbit (Credit : NASA)

The problem Fernando set out to solve is growing more urgent by the day. Last year, multiple satellites entered Earth's atmosphere daily, yet authorities lack independent verification of where they actually landed, whether they broke apart, or if toxic fragments survived to reach the ground. Current tracking relies on radar measurements of a decaying orbit to predict atmospheric entry, but these predictions can miss by thousands of kilometres in the worst cases.

Fernando and colleague Constantinos Charalambous from Imperial College London tested their seismic tracking method on China's Shenzhou-15 orbital module when it reentered on 2 April 2024. Measuring just over 1 metre wide and weighing more than 1.5 tons, the module posed a genuine threat if it struck a populated area.

As the module screamed through the atmosphere at Mach 25-30, roughly ten times faster than the world's speediest fighter jet, it generated powerful sonic booms that propagated downward as shock waves. These vibrations registered on 127 seismometers scattered across southern California, creating a trail of seismic pings as the debris streaked northeast over Santa Barbara and Las Vegas.

This photo was made at Terlingua, Big Bend National Park, Texas, USA. It depicts the night sky including the Milky Way and the rare sight of the Zodiacal Light to the right, and captured the reentry of Shenzhou 15 on the bottom right (Credit : Astrovenator)

This photo was made at Terlingua, Big Bend National Park, Texas, USA. It depicts the night sky including the Milky Way and the rare sight of the Zodiacal Light to the right, and captured the reentry of Shenzhou 15 on the bottom right (Credit : Astrovenator)

By analysing the intensity and timing of these seismic readings, the researchers reconstructed the module's entire trajectory, calculated its speed and altitude, and pinpointed where it fragmented. Their seismic data revealed the module's actual path lay approximately 40 kilometres north of the trajectory predicted by U.S. Space Command, a significant discrepancy that demonstrates why better tracking matters.

The implications extend beyond simply locating crash sites. Falling debris often produces toxic particulates that can linger in the atmosphere for hours, drifting on weather patterns to expose populations far from the impact zone. Knowing the actual trajectory helps authorities track where these contaminants travel and identify communities at risk.

Quick retrieval of landed debris proves especially critical when hazardous materials are involved. Fernando points to the 1996 Russian Mars 96 spacecraft, which carried a radioactive power source. Though believed to have burned up completely, scientists later found artificial plutonium in a Chilean glacier, suggesting the power source ruptured during descent and contaminated the area. The debris's location was never confirmed at the time.

The new seismic tracking method provides near real time information that complements existing radar data, offering authorities an independent verification of where debris actually went rather than where models predicted it should go. As satellite launches accelerate and orbital debris accumulates, such tracking tools become increasingly vital for protecting both people and the environment from falling space junk.

Source : Scientists devise way to track space junk as it falls to Earth

Universe Today

Universe Today