Bacteria and the viruses that infect them have been locked in an evolutionary battle for billions of years. Bacteria evolve defences against viral infection and viruses develop new ways to breach those defences. This process shapes microbial ecosystems across Earth, from ocean depths to soil communities. But what happens when you take that battle to space?

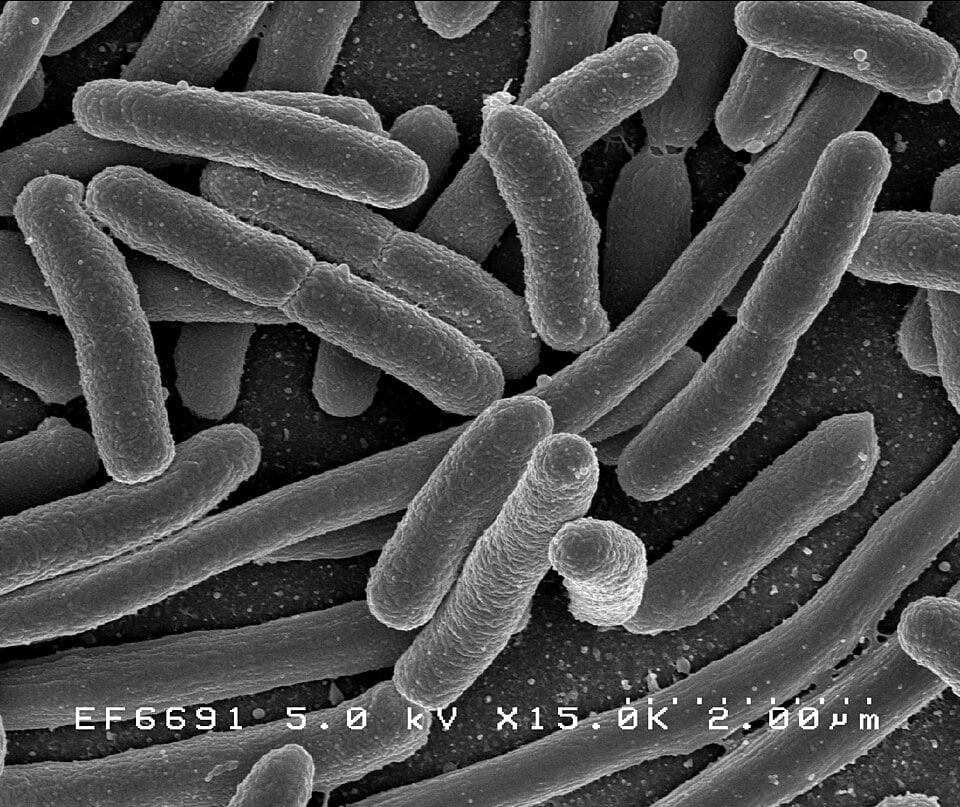

Phil Huss and his colleagues at the University of Wisconsin-Madison decided to find out by sending samples of *E. coli* bacteria infected with T7 virus to the International Space Station. They compared how the virus-bacteria interaction unfolded in microgravity versus identical samples kept on Earth, watching evolution play out in real time under fundamentally different physical conditions.

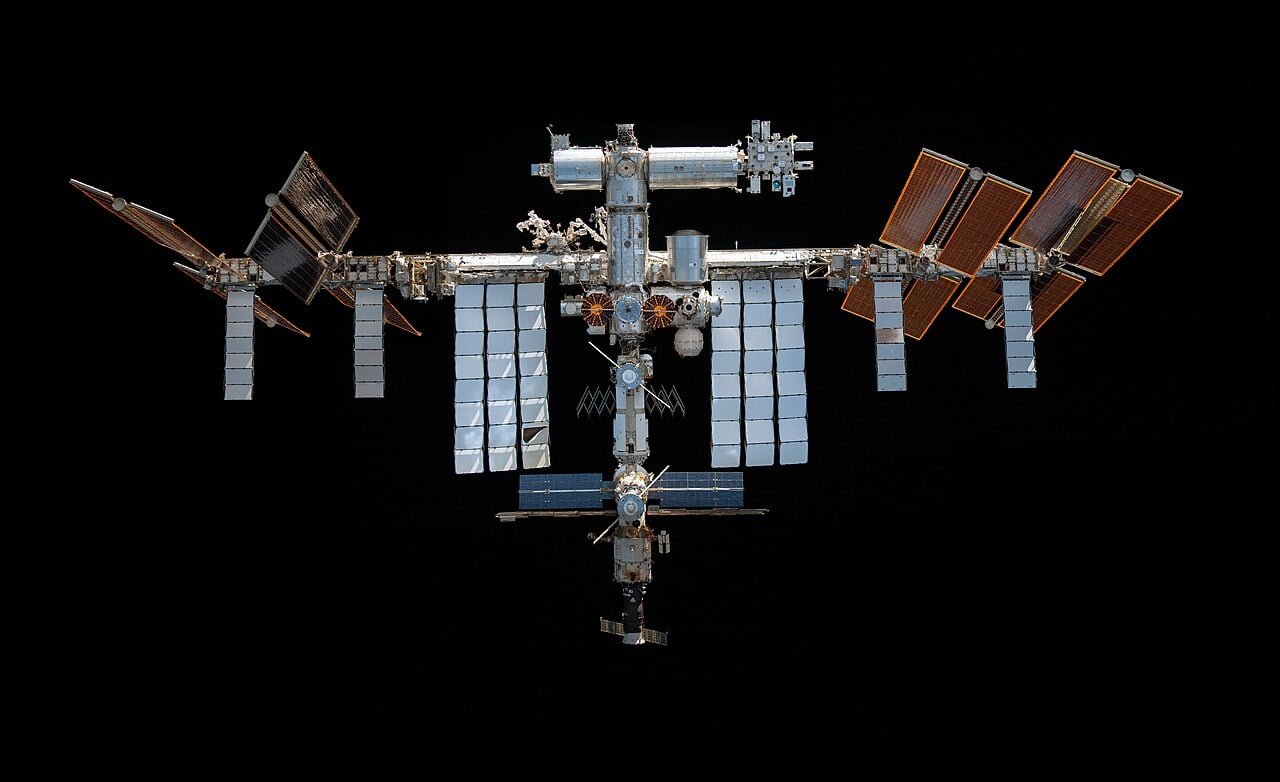

The International Space Station pictured from the SpaceX Crew Dragon (Credit : NASA)

The International Space Station pictured from the SpaceX Crew Dragon (Credit : NASA)

While the T7 viruses eventually managed to infect their bacterial hosts aboard the station, everything happened differently than on Earth. Whole genome sequencing revealed that both the viruses and bacteria accumulated distinctive mutations specific to the microgravity environment, changes that simply don't appear in terrestrial populations.

The space dwelling viruses gradually developed mutations that could enhance their infectivity and improve their ability to bind to receptors on bacterial cell surfaces. Meanwhile, the orbital *E. coli* populations accumulated their own suite of protective mutations, helping them survive both the viral onslaught and the challenges of near weightlessness itself.

Microgravity fundamentally alters the physics of how viruses encounter bacteria. On Earth, gravity influences fluid dynamics and settling behaviours that affect collision rates between viruses and their targets. In orbit, those familiar rules no longer apply. The researchers found that infection proceeded more slowly in space, suggesting that these physical changes genuinely matter for viral success.

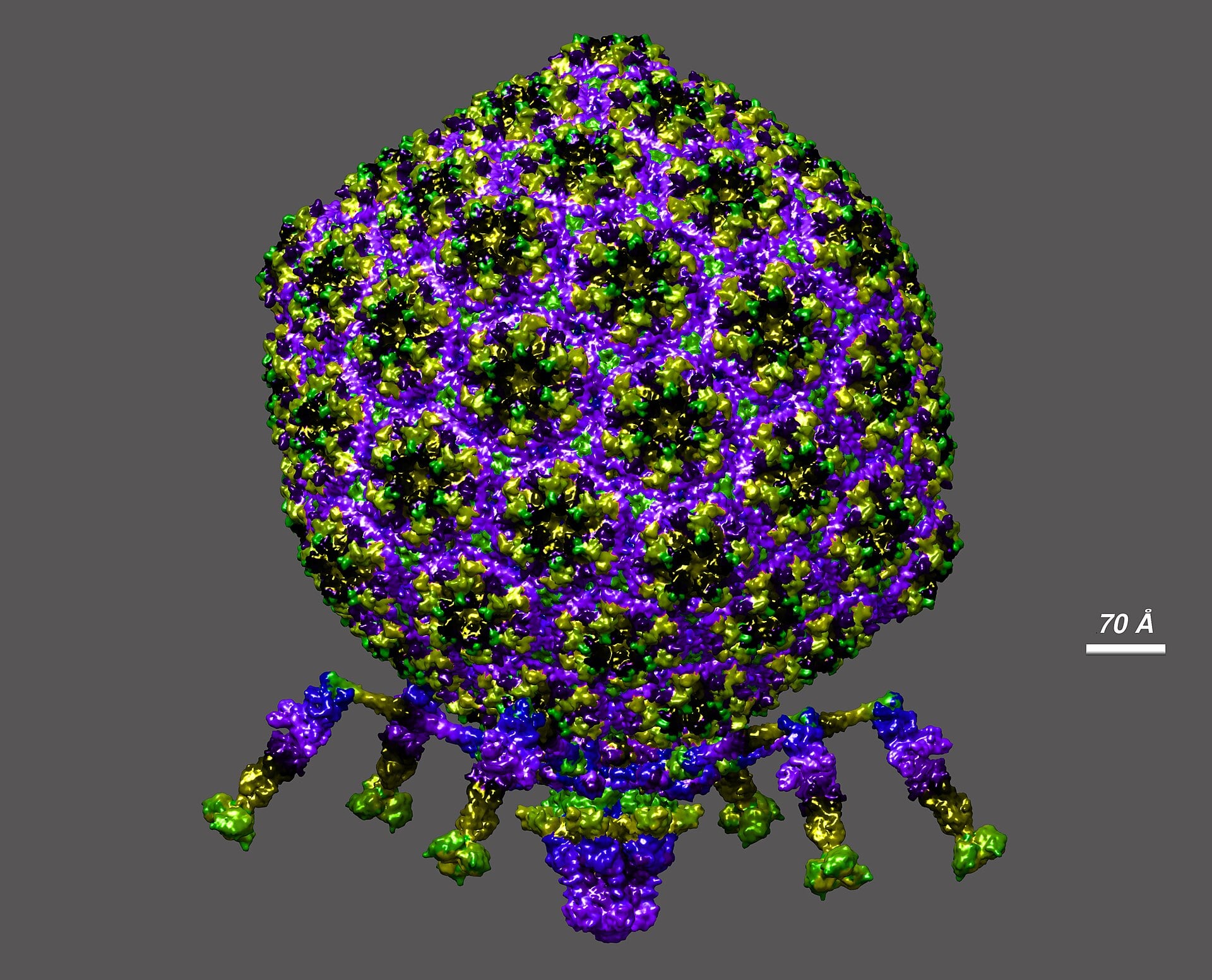

Artist impression of the T7 virus structure at atomic resolution (Credit : Dr. Victor Padilla-Sanchez, PhD)

Artist impression of the T7 virus structure at atomic resolution (Credit : Dr. Victor Padilla-Sanchez, PhD)

The team then employed a technique called deep mutational scanning to examine changes in T7's receptor binding protein, the molecular key that unlocks bacterial cells. This revealed even more significant differences between microgravity and terrestrial conditions. Most remarkably, some of these space driven adaptations proved useful back on Earth.

When researchers engineered the microgravity associated mutations into T7 and tested them against *E. coli* strains that cause urinary tract infections in humans, the strains normally resistant to T7, the modified viruses showed dramatically improved activity. Evolution in orbit had revealed solutions to problems down here on Earth.

The findings highlight an unexpected benefit of orbital research. By subjecting familiar biological systems to radically different environments, scientists can discover evolutionary pathways and genetic solutions that wouldn't naturally emerge on Earth. The ISS becomes not just a platform for studying space biology, but a laboratory for uncovering new approaches to terrestrial challenges, from antibiotic resistance to microbial ecosystem management.

Source : Aboard the International Space Station, viruses and bacteria show atypical interplay

Universe Today

Universe Today