NASA's Kepler exoplanet-hunting space telescope ended its mission in 2018, but its contribution to exoplanet science is ongoing. It generated a huge dataset, one that astronomers are still working through. Researchers found a new candidate exoplanet in Kepler's data named HD 137010 b that's orbiting a Sun-similar star nearly 150 light-years away. The new exoplanet is only slightly larger than Earth, and its orbit is about as long as Earth's.

HD 137010 b is a little closer to its star than Earth is to the Sun, but the star is a K-dwarf, so it's smaller and less luminous. That means the planet receives about one-third of the heat and light that Earth does, despite being close to its star. HD 137010 b is close to the very outside edge of the star's habitable zone, so it's very cold.

New research published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters presents the discovery. It's titled "A Cool Earth-sized Planet Candidate Transiting a Tenth Magnitude K-dwarf From K2," and the lead author is Alexander Venner. Venner was a PhD student at the Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland in Australia, and is now a post-doc researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

The exoplanet is generating interest not only because it's Earth-like and orbits a Sun-similar star. It also represents a potential first in exoplanet-hunting. HD 137010 b is a candidate for now, but if it's eventually confirmed, it could be the first single-transit detection of an Earth-like world.

"The transit method is currently one of our best means for the detection of potentially habitable “Earth-like” exoplanets," the researchers write. "In principle, given sufficiently high photometric precision, cool Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting Sun-like stars could be discovered via single transit detections; however, this has not previously been achieved."

A single transit has to be very high quality to generate a confirmed exoplanet. This one was comparatively shallow, according to the authors, and exhibited "exceptionally high photometric precision."

"Our analysis of the K2 photometry, historical and new imaging observations, and archival radial velocities and astrometry strongly indicate that the event was astrophysical, occurred on-target, and can be best explained by a transiting planet candidate, which we designate HD 137010 b," the researchers explain.

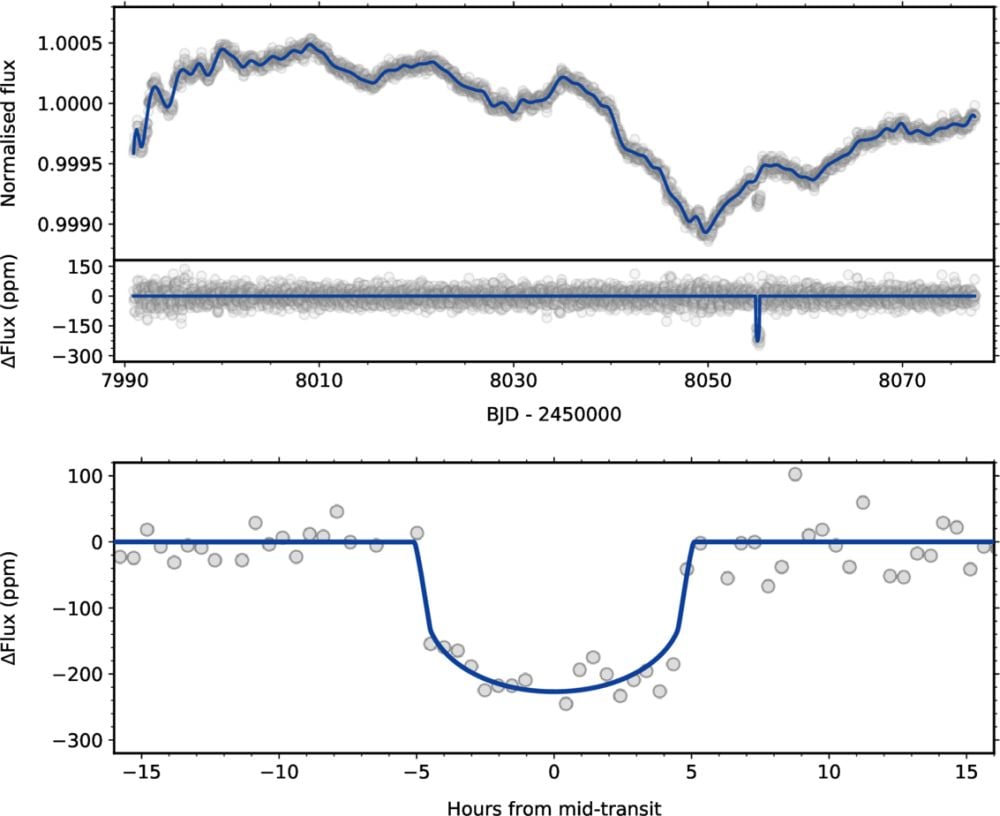

*The three panels in this figure represent the transit detected in Kepler's K2 extended mission. The top panel shows the star's light curve. The middle panel shows the same curve with long-term variability removed and the transit at BJD ≈ 2458055.1. The bottom panel shows the transit event itself. Image Credit: Venner et al. 2026. ApJL*

*The three panels in this figure represent the transit detected in Kepler's K2 extended mission. The top panel shows the star's light curve. The middle panel shows the same curve with long-term variability removed and the transit at BJD ≈ 2458055.1. The bottom panel shows the transit event itself. Image Credit: Venner et al. 2026. ApJL*

The transit depth relates to the planet-to-star radius ratio. The transit had a depth of 225 ppm, which means that the planet blocks about 0.0225% of the star's light when it transits. That means that it has a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which is critical in exoplanet detections, and surprising for a shallow detection. With an SNR of about 30, that means the signal is about 30 times stronger than noise. That represents exceptional photometric precision.

The planet itself receives less solar flux than Mars. Its equilibrium temperature, which occurs when incoming radiation equals outgoing radiation, is between -68C and -85C. That leads to questions about its position in its solar system, and whether it could be in the habitable zone.

"It therefore appears likely that HD 137010 b is among the coolest Earth-sized transiting planets yet discovered orbiting a Sun-like star, and we are motivated to consider whether HD 137010 b lies in the HZ," the researchers write.

The estimated equilibrium temperatures suggest that there's no liquid water, but without knowing what atmosphere the planet might have, liquid water can't be completely ruled out. The team determined that depending on the transit model used, HD 137010 b is within the conservative and optimistic HZ limits 40% and 51% of the time. Conversely, there's a 50% chance that it's beyond the habitable zone.

An atmosphere rich in CO2 could provide the warmth necessary for liquid water, and that's at least possible according to the authors. "However, a plausible alternative scenario is that the surface of HD 137010 b is frozen (a “snowball” climate)," they explain.

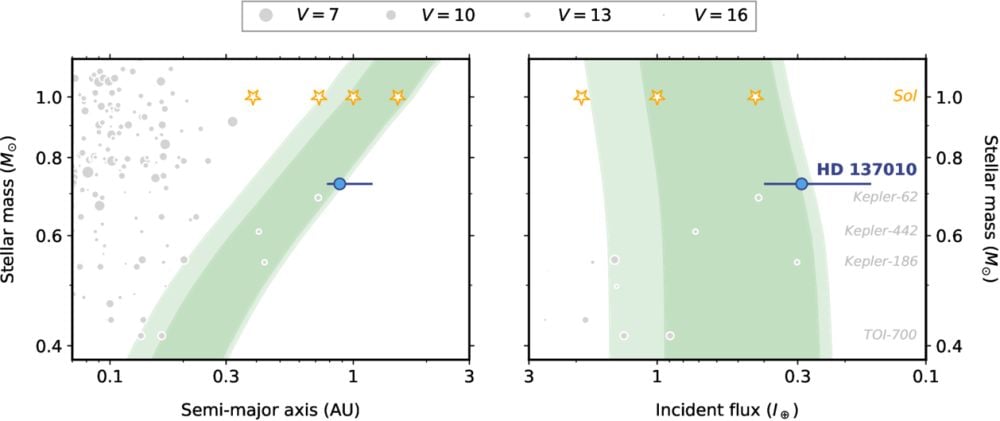

*These two panels sum up some of the findings and put HD 137010 b in context. The left panel shows stellar mass on the y-axis and semi-major axis on the x-axis. The grey points are known transiting planets smaller than <1.6 R⊕ orbiting 0.4–1.2 M⊙ stars. Our Solar System's terrestrial planets are represented by the orange stars, and the two green-shaded regions represent optimistic and conservative habitable zones. "HD 137010 b is an exceptional example of an Earth-sized planet orbiting around the outer edge of the HZ of a bright Sun-like star," the authors explain. Image Credit: Venner et al. 2026. ApJL*

*These two panels sum up some of the findings and put HD 137010 b in context. The left panel shows stellar mass on the y-axis and semi-major axis on the x-axis. The grey points are known transiting planets smaller than <1.6 R⊕ orbiting 0.4–1.2 M⊙ stars. Our Solar System's terrestrial planets are represented by the orange stars, and the two green-shaded regions represent optimistic and conservative habitable zones. "HD 137010 b is an exceptional example of an Earth-sized planet orbiting around the outer edge of the HZ of a bright Sun-like star," the authors explain. Image Credit: Venner et al. 2026. ApJL*

When it comes to the transit method, an exoplanet becomes confirmed when we observe two or three transits. While this single transit is exceptionally strong, it's still just a solitary transit. Astronomers need more data before HD 137010 b can be confirmed. NASA's TESS spacecraft, Kepler's successor, is still operating despite going into safe mode briefly this month. With a little luck, it could detect another transit and provide confirmation. Or maybe the ESA's CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite) could do it.

One of the problems is the exoplanet's Earth-like nature. With an orbit that takes about one Earth-year, we have to wait a long time before HD 137010 b transits its star again.

But even without data from additional transits, the researchers are pretty confident it will eventually be confirmed. No other explanation fits the transit data as well. While they only have a single transit to work with, data from other sources like HARPS and Hipparcos–Gaia, as well as some archival images and new images from the Gemini South Telescope, strengthen the detection.

"Through detailed analysis of available observations of HD 137010, we have excluded all conventional hypotheses for the transit event other than a transiting exoplanet; however, confirmation of the planetary hypothesis will require observation of a second transit or another form of additional detection," the researchers explain.

The main things that could negate the detection are background stars or companion stars, and neither of those are present.

"In summary, we find that there is no evidence for either background sources or comoving companion stars that could have interfered with or contaminated the K2 photometry," the authors conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today