Despite the US administration's threats to cancel the nearly complete Nancy Grace Roman Telescope, it's on track to launch this year or next. When it's launched and sent toward its orbit at the Sun-Earth L2 point, it'll carry two instruments and be ready to tackle three new astronomical surveys. One of them is the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey (GBTDS).

THe GBTDS is a three-year, six-season survey that will see the telescope revisit six central regions of the Milky Way for 72 hours each season. It's aimed at finding exoplanets in the Milky Way's densely-populated galactic bulge. Scientists expect the Roman to find 1,000 new exoplanets using the gravitational microlensing technique alone.

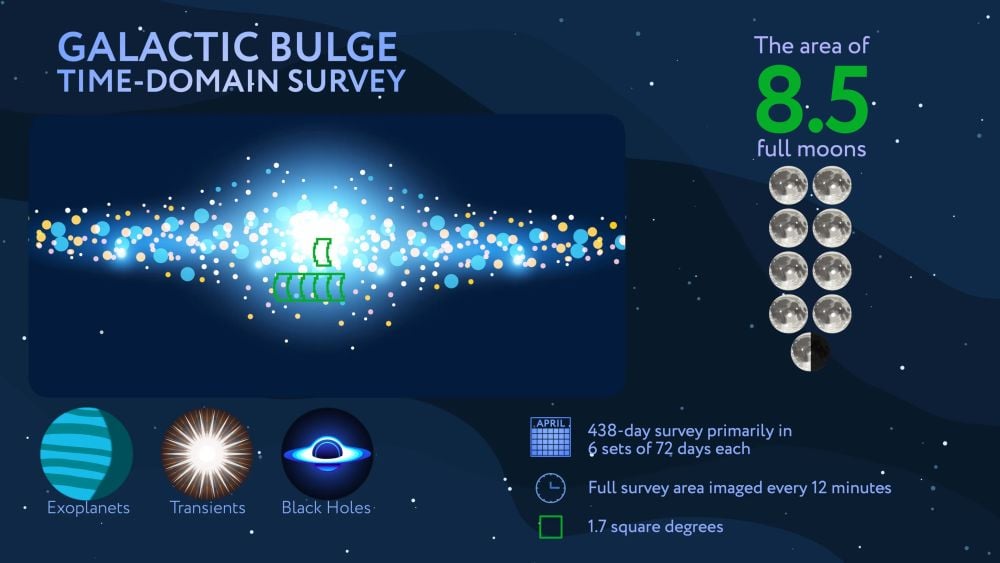

*This infographic highlights some aspects of the Nancy Grace Roman's Galactic Bulge Time Domain Survey. It's the smallest of the space telescope's three core surveys, but will likely find the most distant exoplanet ever detected, along with black holes and neutron stars. Image Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center*

*This infographic highlights some aspects of the Nancy Grace Roman's Galactic Bulge Time Domain Survey. It's the smallest of the space telescope's three core surveys, but will likely find the most distant exoplanet ever detected, along with black holes and neutron stars. Image Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center*

The observing fields were chosen after deep deliberation by the astronomical community. There were trade-offs and compromises, and the six observation fields were chosen to deal with certain limitations and to accomplish specific goals.

Five of them are continguous, while the sixth is centered on the galactic center specifically. The five contiguous fields were chosen partly because they have less foreground extinction from dust. They're also packed with stars, which means the telescope can find more gravitational microlenses and more exoplanets.

The galactic center was chosen because of strong community interest. It has higher dust extinction, which means fewer gravitational microlenses, but also has a wider diversity of objects. The sixth field includes Sagittarius A-star and its surroundings, a vital subject in astronomy and astrophysics. It also hosts massive star clusters like the Archers cluster and the Quintuplet cluster.

Other observational constraints also determine the size and location of the fields. "Survey area, imaging cadence, stellar density, and dust extinction all affect microlensing yields, transiting detection yields, and asteroseismic detections and measurements," a Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) page explains.

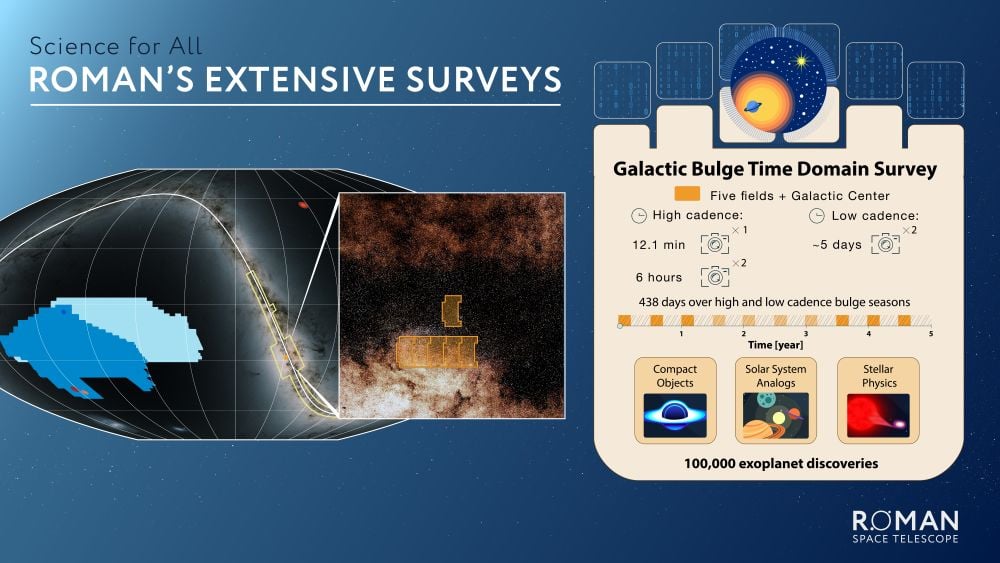

This figure shows and summarizes Roman's GBTDS fields (highlighted in orange) on an optical image of the Galactic Bulge. The astronomy science community settled on six observing fields. Image Composition: J. Olmsted, J. Kang, and C. Nieves (STScI). Background sky image: ESA/Gaia/DPAC. Acknowledgement: Javier Sanchez (STScI).

This figure shows and summarizes Roman's GBTDS fields (highlighted in orange) on an optical image of the Galactic Bulge. The astronomy science community settled on six observing fields. Image Composition: J. Olmsted, J. Kang, and C. Nieves (STScI). Background sky image: ESA/Gaia/DPAC. Acknowledgement: Javier Sanchez (STScI).

A defining feature of the Milky Way's galactic bulge is its dense stellar population. By examining this region repeatedly, the Roman will monitor the movement and brightness changes of millions of stars, and detect changes indicating orbiting exoplanets. The transit method has found the large majority of the known exoplanet population, and the space telescope will use it to detect more than 100,000 new exoplanets, according to scientists.

The transit method has proven effective, but it has its limitations the same as any other method. It tends to find planets around dim stars, and planets that are massive and can block out a lot of a star's light. It's also biased to detecting planets that are very close to their stars on short orbits.

Gravitational microlensing is different. It works when a massive object like a star, or a star with planets, moves in front of a distant background star, from our observational perspective. The foreground object is the desired target, and acts as the primary lens. When it lines up with a background star, the foreground object magnifies the light making it brighten temporarily. If the foreground object has an exoplanet, the exoplanet acts as a secondary lens, and will cause its own, brief brightening. Its gravitational effect on the light from the background star signals its presence.

“Microlensing events are rare and occur quickly, so you need to look at a lot of stars repeatedly and precisely measure brightness changes to detect them,” said astrophysicist Benjamin Montet from the University of New South Wales in Sydney. “Those are exactly the same things you need to do to find transiting planets, so by creating a robust microlensing survey, Roman will produce a nice transit survey as well.”

Gravitational microlensing casts a much wider net than the transit method. It can detect exoplanets much further away than the transit method can. It's particularly effective at finding exoplanets on wider orbits, and exoplanets around extremely dim stars. It can also detect rogue planets, something completely beyond the capabilities of the transit method.

While we've learned a lot about the galactic exoplanet population, especially from NASA's Kepler and TESS missions, they both relied on the transit method. That means our sample of the exoplanet population is biased, a problem that was understood during these missions' design phases.

Our exoplanet surveys have given us a picture of the exoplanet population that is not accurate. As a result, we can't place our own Solar System in the right context. For example, we don't know how common Earth-like planets might be. The Roman Space Telescope will address that.

“This survey will be the highest precision, highest cadence, longest continuous observing baseline survey of our galactic bulge, where the highest density of stars in our galaxy reside,” said Jessie Christiansen of Caltech/IPAC, who served as co-chair of the committee that defined the Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey.

“For the first time, we will have a big picture understanding of Earth and our solar system within the broader context of the exoplanet population of the Milky Way galaxy,” Christiansen said in a press release. “We still don’t know how common Earth-like planets are, and the Roman Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey will provide us with this answer.”

But there's more to the GBTDS than exoplanets. The survey will also detect stars, black holes, brown dwarfs, and even some rogue planets. Scientists think it will also detect more than 1,000 neutron stars.

“There is an incredibly rich diversity of science that can be done with a high-precision, high-cadence survey like this one,” said Dan Huber of the University of Hawaii, the other survey co-chair.

Astronomers are looking forward to the survey's data because the galactic center and bulge are not well understood. The region is obscured by heavy dust, and it's also about 26,000 light-years away. It's also so densely packed that resolving individual stars has been an ongoing challenge. We lack detailed knowledge about the stellar population in the region, and have almost zero knowledge of the exoplanet population. Gaia and the JWST have made some progress in observing the region, but the infrared Roman Space Telescope is about to address these scientific shortcomings in a more thorough way.

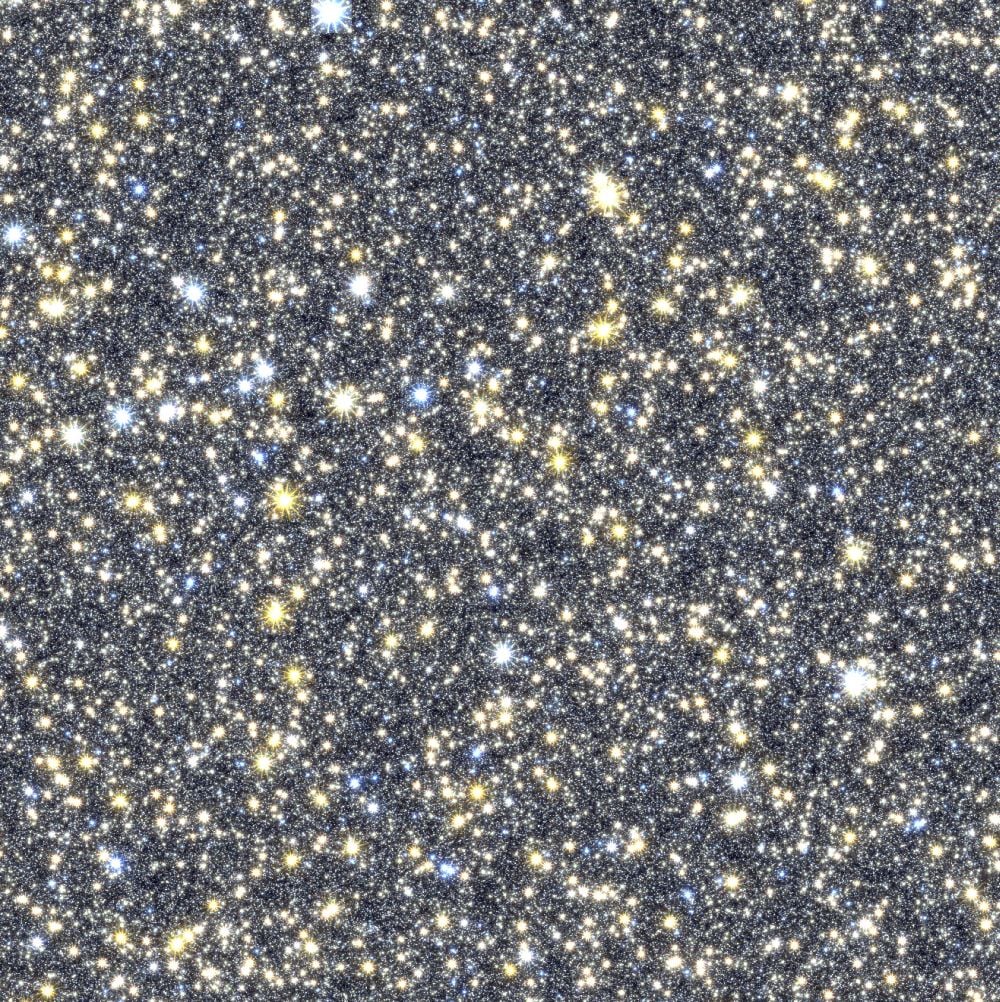

The Milky Way's central region is so densely packed with stars that it's difficult to spot them individually. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will address that. This image is a simulated image of what the Roman Telescope will see when it probes the region. Image Credit: Matthew Penny (Louisiana State University)

The Milky Way's central region is so densely packed with stars that it's difficult to spot them individually. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will address that. This image is a simulated image of what the Roman Telescope will see when it probes the region. Image Credit: Matthew Penny (Louisiana State University)

“The stars in the bulge and center of our galaxy are unique and not yet well understood,” Huber said. “The data from this survey will allow us to measure how old these stars are and how they fit into the formation history of our Milky Way galaxy.”

The telescope is currently on track to launch in the Fall of 2026, with a scheduled launch no later than May 2027. After a journey of about one month, it will enter a halo orbit at Sun-Earth L2. There'll be a commissioning phase, and then shortly after that, the powerful new telescope will get down to business.

Universe Today

Universe Today