All across the Universe, black holes devour stars that stray too close. Often it's a supermassive black hole that tears a star apart in what's known as a tidal disruption event. But sometimes, it's a stellar mass black hole, and its victim is its binary star partner.

When massive stars reach the end of their lives, they can explode as supernovae and form black holes. Since stars are often in binary relationships with a partner, this can create a situation where the companion star is now orbiting a dangerous black hole. These companion stars are in a tough spot.

But that's a broad overview of the phenomenon. In reality there's a lot more detail and mystery in the world of exploding stars, black holes, and their companions.

One mysterious type of stellar explosion is the Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transient (LFBOT). They're explosions similar to supernovae and gamma-ray bursts (GRB), but are extremely bright in optical light. They also evolve rapidly and emit mostly blue light.

A team of astronomers have discovered the most energetic and luminous LFBOT ever found. It's designated AT2024wpp and nicknamed Whippet. The Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) first detected it, and it was observed quickly thereafter by the Liverpool Telescope in the Canary Islands and NASA's Swift satellite in space. Observations showed that it was 1.1 billion light-years away.

The discovery and analysis were presented at the 247th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society, and will be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The research is titled "Multiwavelength Modeling of the Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transient AT2024wpp," and is currently available at arxiv.org. Daniel Perley, Associate Professor of Astrophysics at Liverpool John Moores University, one of the authors and presented the research at AAS 247.

"The name basically tells you what they are, at least observationally," Perley said in his presentation at AAS 247. "They are as bright as a powerful supernova, but they play out much faster, appearing and disappearing on timescales of just a few days or weeks."

Astrophysicists are still trying to understand the exact nature of these powerful LFBOTs.

"We still don't know what causes them, however, but the leading theories are that they're the result of a massive star collapsing into a black hole, or perhaps from a star passing to close to a black hole and being disrupted by it," Perley continued. "But there are many ideas in the literature, and they have captivated the community from them to this day."

Astronomers keep detecting more of them, piquing their curiosity and capturing their attention. Most of them are at vast distances, or have been found too late, limiting opportunities to observe and study them. Observing their early phases is critical to understanding them, and with Whippet, the researchers were able to catch it early.

"Luminous fast blue optical transients (LFBOTs) are a growing class of enigmatic energetic transients," the researchers write. "Their power source is currently unknown, but proposed models include engine-driven supernovae, interaction-powered supernovae, shock cooling emission, intermediate mass black hole tidal disruption events (IMBH TDEs), and Wolf-Rayet/black hole mergers, among others."

That's a long list of potential causes. Each of these scenarios creates different light curves that can be tested against models. "We take models from multiple scenarios and fit them to the AT2024wpp optical, radio, and X-ray light curves to determine if which of these scenarios can best describe all aspects of the data," the authors write.

Unfortunately, none of the existing models of these causes matches Whippet's emissions. But there's other data, and it led the researchers to a conclusion. "We show that none of the multiwavelength light curve models can reasonably explain the data, although other physical arguments favour a stellar mass/IMBH TDE of a low mass star and a synchrotron blast wave," the authors explain.

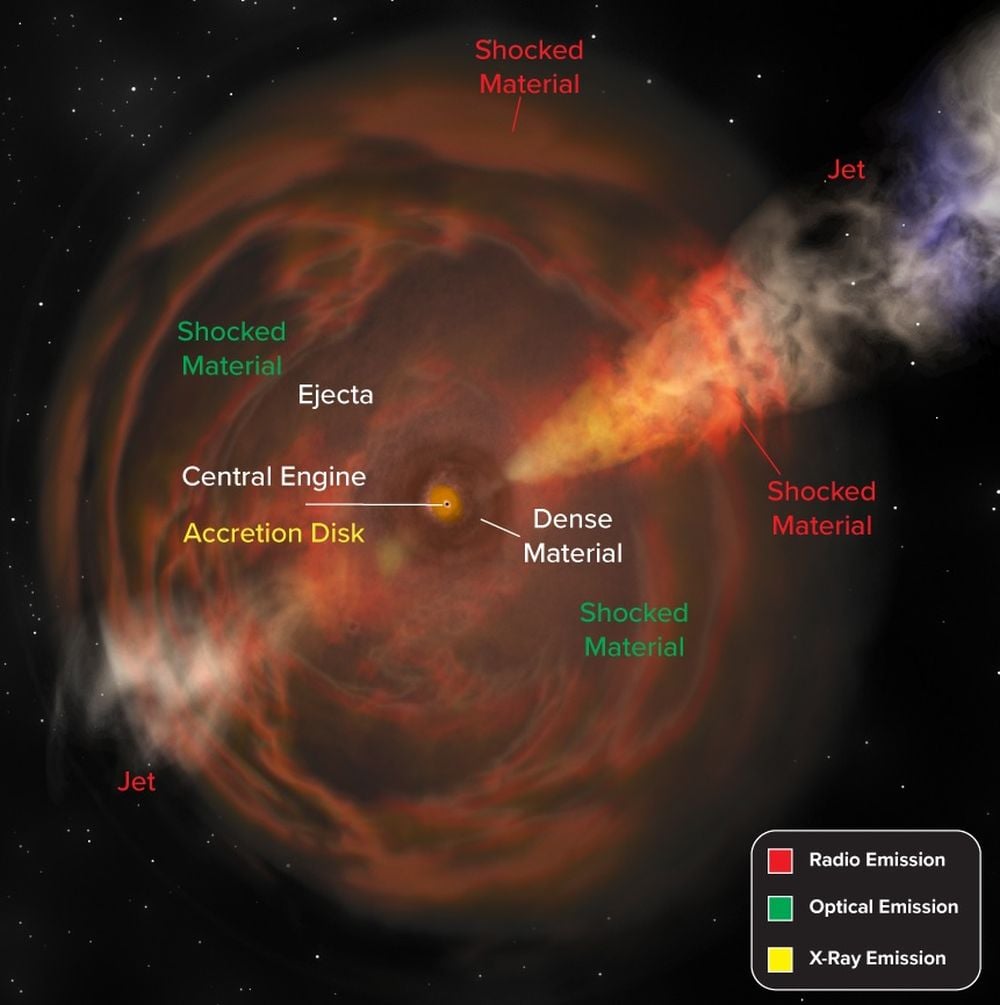

*This illustration shows some of the structure and characteristics of LFBOTs. However, there's still a lot of uncertainty and astrophysicists are eager to find and study more examples. Image Credit: By Bill Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSFhttps://public.nrao.edu/blogs/author/billsaxton/ - https://public.nrao.edu/news/new-class-cosmic-explosions/https://public.nrao.edu/media-use/https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Template:NRAO, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=114339172*

*This illustration shows some of the structure and characteristics of LFBOTs. However, there's still a lot of uncertainty and astrophysicists are eager to find and study more examples. Image Credit: By Bill Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSFhttps://public.nrao.edu/blogs/author/billsaxton/ - https://public.nrao.edu/news/new-class-cosmic-explosions/https://public.nrao.edu/media-use/https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Template:NRAO, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=114339172*

In plain language, that means that either a stellar mass black hole or an intermediate mass black hole tore a companion star apart in a tidal disruption event. The event also created a synchrotron blast wave, which creates synchrotron radiation as it travels through space. The blast wave accelerates electrons to near the speed of light, and as they travel, they interact with magnetic fields and are forced to spiral around those fields.

“We discovered what we think is a black hole merging with a massive companion star, shredding it into a disk that feeds the black hole," lead author Perley said in a press release. "It’s a rare and awe-inspiring phenomenon.”

This is one of the most powerful events ever witnessed in the cosmos. It was more energetic than a supernovae, which is truly amazing. It's peak energy release was 400 billion times brighter than the Sun.

“Even though we suspected what is was, it was still extraordinary,” said Perley. “This was many times more energetic than any similar event and more than any known explosion powered by the collapse of a star."

“Not only do these events help us identify black holes, they provide a new way to identify where black holes occur and how they form and grow, and the physics of how this happens,” Perley added.

But there was more to the event. As matter from the companion star spiralled toward the black hole, it not only released x-rays but a powerful wind. That wind eventually collided with gas that was previously released by the star before it met its end. The shock wave from this collision produced the bright optical emissions, and some UV emissions in the days following the explosion. Once the shock wave reached the limit of the bubble of ejected material, it fizzled out.

Astrophysicists understand this mechanism, but one other thing remained mysterious. There were no recognizable chemical fingerprints in the month following the explosion, according to observations with Keck, Magellan, and the VLT. This is unusual, but the authors say it's because x-rays ionized the material, stripping away electrons and hiding their chemical signatures.

Then, as time passed and the event faded from view, weak hydrogen and helium signatures appeared. The researchers were surprised to find the helium moving at more than 6,000 kilometers per second. This suggested that a densely bound cloud was intact and moving towards us.

The researchers have settled on the most likely explanation for Whippet, but caution that this explanation may not be accurate for other LFBOTs.

Perley put it simply in his presentation at AAS 247, saying "Its properties can be explained by the disruption and accretion of a massive star by a black hole companion."

Note: the text from Perley's presentation at AAS 247 is lightly edited.

Universe Today

Universe Today