Stars are known for their stellar winds, streams of gas and charged particles from their upper atmospheres that collide with the interstellar medium. These winds can create bow shocks in the surrounding gas. But astronomers were surprised to find a bow shock near a white dwarf star, which are sometimes called dead stars or zombie stars.

White dwarfs are called zombie stars because they emit only remnant energy. They left the main sequence long ago, and no longer fuse lighter elements into heavier elements, which is how stars shine. They're known for only weak or insignificant stellar winds that shouldn't produce the telltale bow shocks.

Astronomers found the unexpected bow shock around RXJ0528+2838, which is called a *short-period polar-type cataclysmic variable* in scientific terms. That means it's a binary star that features a strongly magnetized white dwarf star with a low-mass companion star in a tight orbit.

The discovery is presented in new research in Nature Astronomy titled "A persistent bow shock in a diskless magnetized accreting white dwarf." The co-lead author is Simone Scaringi. Scaringi is an Associate Professor in the Physics Department at Durham University in the UK.

While solitary white dwarfs emit only very weak stellar winds, things can change when the dwarf has a binary partner. But only in certain cases.

"Stellar bow shocks form when an outflow interacts with the interstellar medium," the authors write. "In white dwarfs accreting from a binary companion, outflows are associated with strong winds from the donor star, the accretion disk or a thermonuclear runaway explosion on the white dwarf surface."

But RXJ0528+2838 (hereafter referred to as 2838), doesn't conform to any of those mechanisms.

Bow shocks are useful diagnostic features that can reveal a lot about the energy and mechanisms behind their creation. "When stellar outflows ram into interstellar gas under the right conditions, they produce bow shocks – curved, comet-like arcs of shocked material, similar to the wave that builds up in front of a ship. Bow shocks are powerful tools, because their size and shape let us directly gauge how much energy is carried by the outflow," co-author Noel Castro Segura said in a press release.

“We found something never seen before and, more importantly, entirely unexpected,” said author Simone Scaringi in a separate press release.

“Our observations reveal a powerful outflow that, according to our current understanding, shouldn’t be there,” said Krystian Iłkiewicz. Iłkiewicz is a postdoctoral researcher at the Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center in Warsaw, Poland and co-lead author of the study.

White dwarfs in binary systems typically draw material away from their companions, which collects in a disk of material around the white dwarf. The disk is kind of like purgatory: some of the material falls into the white dwarf, while some is ejected as a powerful stellar wind. But 2838 has no disk.

“The surprise that a supposedly quiet, discless system could drive such a spectacular nebula was one of those rare ‘wow’ moments,” says Scaringi.

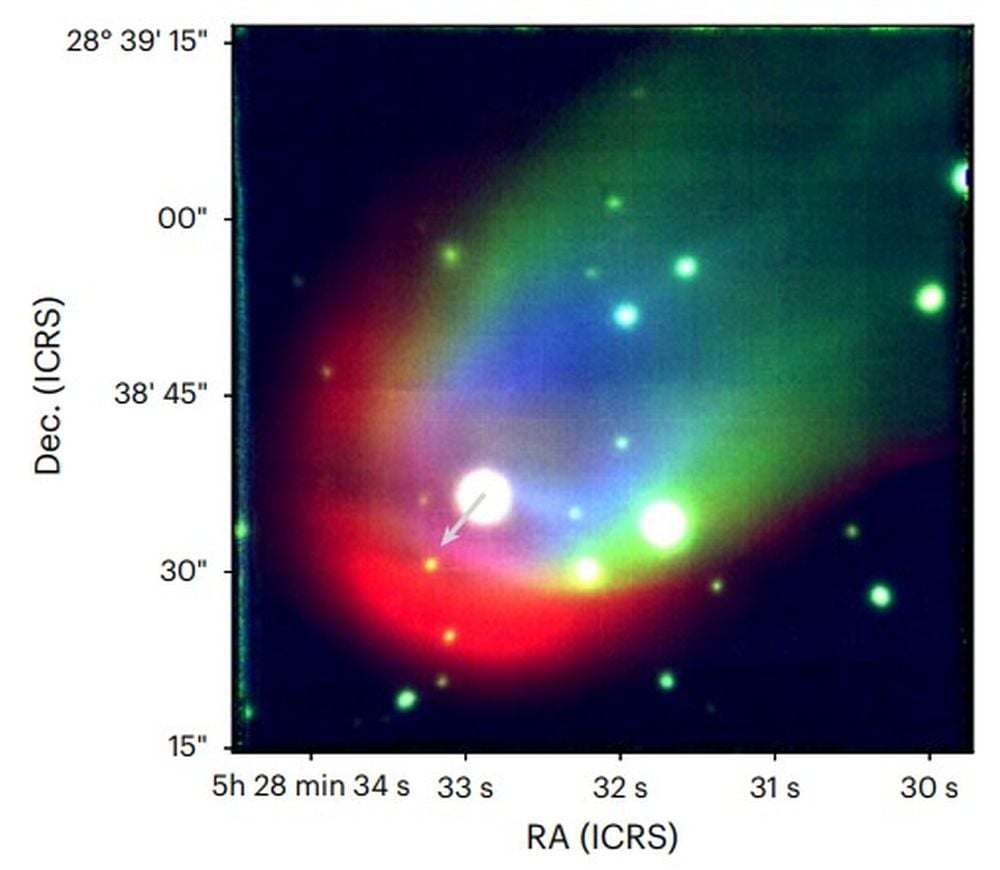

This is a false-colour image of RXJ0528+2838 and its surrounding nebula. The red, green and blue channels correspond to the Hα, N ii, and Oiii lines, respectively, from MUSE data. The small grey arrow shows the star's motion through space. Image Credit: Iłkiewicz et al. 2026 NatAstr.

This is a false-colour image of RXJ0528+2838 and its surrounding nebula. The red, green and blue channels correspond to the Hα, N ii, and Oiii lines, respectively, from MUSE data. The small grey arrow shows the star's motion through space. Image Credit: Iłkiewicz et al. 2026 NatAstr.

The unexpected nebulosity around 2838 was first spotted in images from the Isaac Newton Telescope in Spain, an optical facility on La Palma in the Canary Islands. Curious about its nature and its source, the team of researchers then examined it more closely with the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) instrument on the Very Large Telescope.

“Observations with the ESO MUSE instrument allowed us to map the bow shock in detail and analyse its composition. This was crucial to confirm that the structure really originates from the binary system and not from an unrelated nebula or interstellar cloud,” Iłkiewicz explains.

"The resolved bow shock is shown to be inconsistent with a past thermonuclear explosion or with being inflated by a donor wind, ruling out all accepted scenarios for inflating a bow shock around this system," the authors write in their research. The thermonuclear explosion refers to a Type Ia supernova, where a white dwarf accretes matter from a donor companion. The matter accumulates on the white dwarf's surface until a critical mass is reached, triggering an explosion. In a separate scenario, the donor wind refers to a stellar wind coming from the companion star.

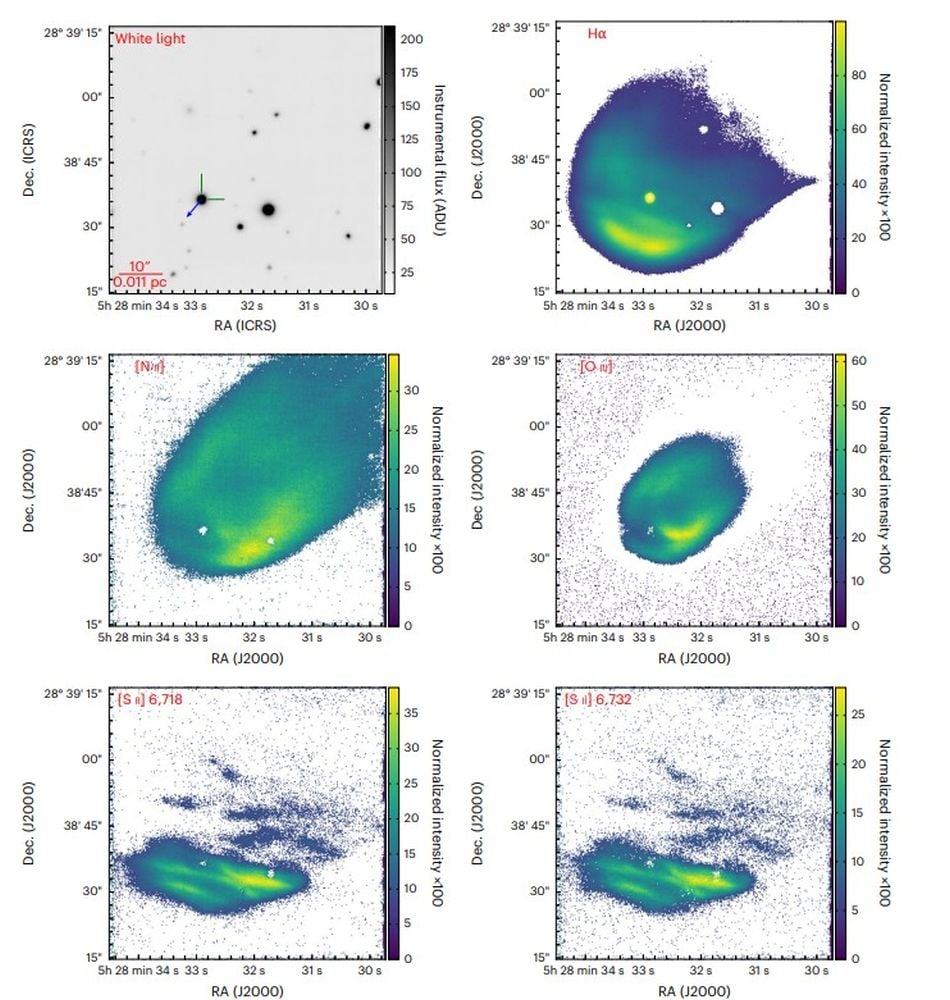

These MUSE images show how the instrument examined 2838 in greater detail. Each panel shows a different emission line, and overall, they show the extended nature of the nebulosity and bow shock around the star. The upper left panel is for white light. "The spatial extent of the bow shock in RXJ0528+2838 varies significantly depending on the emission line used to trace it," the authors write. Image Credit: Iłkiewicz et al. 2026 NatAstr.

These MUSE images show how the instrument examined 2838 in greater detail. Each panel shows a different emission line, and overall, they show the extended nature of the nebulosity and bow shock around the star. The upper left panel is for white light. "The spatial extent of the bow shock in RXJ0528+2838 varies significantly depending on the emission line used to trace it," the authors write. Image Credit: Iłkiewicz et al. 2026 NatAstr.

With both of those mechanisms eliminated as causes of the bow shock, the researchers were driven to dig more deeply into the system with the help of astrophysical models.

"Modelling of the energetics reveals that the observed bow shock requires a persistent power source with a luminosity significantly exceeding the system accretion energy output," the authors explain.

"Given that all the established bow-shock formation scenarios fail to explain the observations of RXJ0528+2838, we speculate that there is a new energy-injection mechanism into the ISM from this system," the authors write.

The bow shock's characteristics suggest that the the white dwarf has been driving the powerful stellar wind for at least 1,000 years. "This implies the presence of a powerful, previously unrecognized energy-loss mechanism—potentially tied to magnetic activity—that may operate over sufficiently long timescales to influence the course of binary evolution," the authors explain in their research.

*This image from the Digitized Sky Survey (DSS) shows the region of the sky around the dead star RXJ0528+2838, which is located at the very centre of the image. Image Credit: ESO/Digitized Sky Survey 2. Acknowledgement: D. De Martin*

*This image from the Digitized Sky Survey (DSS) shows the region of the sky around the dead star RXJ0528+2838, which is located at the very centre of the image. Image Credit: ESO/Digitized Sky Survey 2. Acknowledgement: D. De Martin*

About 20% of white dwarfs are known to have very powerful magnetic fields, and MUSE showed that 2838 does indeed have a strong magnetic field. “Our finding shows that even without a disc, these systems can drive powerful outflows, revealing a mechanism we do not yet understand. This discovery challenges the standard picture of how matter moves and interacts in these extreme binary systems,” Iłkiewicz explains.

"Rather than tapping into the gravitational potential energy, we consider that the power source responsible for inflating the bow shock could be tapping into the strong stored magnetic energy density of the WD, so we ask how long it might take for this to become depleted at the power required to inflate the bow shock," the researchers write.

While 2838 has a powerful magnetic field, the data shows it's not strong enough to explain the star's wind and nebulosity. The current field is only powerful enough to account for a bow shock lasting a few hundred years, not 1,000. So this is a partially solved mystery.

“To try and understand this, we really need to try and find more examples elsewhere in the galaxy," co-author Scaringi said. "In this case, this white dwarf is quite close to Earth and therefore we can see it well. The hunt is on now to try and discover more examples of this, to help develop our understanding and offer a physics-based solution to the mystery.”

Upcoming telescopes like the Extremely Large Telescope should find more of these unusual stars. With a larger data set in hand, astrophysicists will likely figure it out one day.

Universe Today

Universe Today