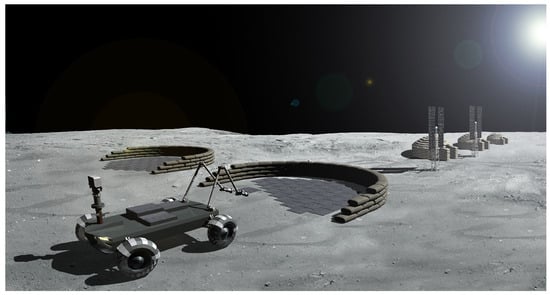

Engineers need good data to build lasting things. Even the designers of the Great Pyramids knew the limestone they used to build these massive structures would be steady when stacked on top of one another, even if they didn’t have tables of the compressive strength of those stones. But when attempting to build structures on other worlds, such as the Moon, engineers don’t yet know much about the local materials. Still, due to the costs of getting large amounts of materials off of Earth, they will need to learn to use those materials even for critical applications like a landing pad to support the landing / ascent of massive rockets used in re-supply operations. A new paper published in Acta Astronautica from Shirley Dyke and her team at Purdue University describes how to build a lunar landing pad with just a minimal amount of prior knowledge of the material properties of the regolith used to build it.

Why build a landing pad at all, though? Couldn’t Starship or a similarly heavy capacity rocket simply land wherever its flight algorithm deems is a flat enough patch of ground? In theory, yes, however, the plume from the retrograde rockets will kick up a massive amount of rock and dust, potentially damaging not only nearby structures (like a fledgling lunar base), but also potentially the rocket itself.

To avoid that fate, mission designers generally agree on the need for a more structured “landing pad” similar to what we use on a near-daily basis on Earth. Recent reports of a Soyuz rocket destroying its landing pad at the Baiknour Cosmodrome notwithstanding, landing pads on Earth are well understood and have done an excellent job serving as the foundation of rocket launches for decades. But can we reproduce them using lunar materials?

Fraser talks about why the lunar south pole is so interset for explorers.Not in the same way we would build them here. Building a landing pad on the Moon would require using local regolith, since the cost of shipping enough concrete to the lunar surface to build a landing pad using Earth-source materials would be prohibitively expensive. But, according to Dr. Dyke, there’s still so much we don’t understand about the mechanical properties of the Moon’s regolith - especially about the strength a member has when it is sintered together, which is the current favorite process for creating a cohesive, hard structure out of in-situ regolith that would serve as a landing pad.

Anyone familiar with lunar regolith testing is probably asking - why don’t they just use simulants to perform some preliminary tests? This material is the closest we can get to the real deal on the Moon, and it’s been used for everything from beneficiation tests to growing plants. But, “simulants are called simulants for a reason,” according to Dr. Dyke. While some of the material properties might be the same, the only way to truly know how a material will react, especially in as unique an environment as the Moon, is to test it in-situ.

There are two main considerations when designing a landing pad - it’s mechanical properties (i.e. stress/strain under force) and its thermal properties (i.e. how much does it expand/contract at different temperatures). While many of the properties of sintered regolith materials are unknown, the authors were able to estimate structural properties based on what little information is available in the literature. One theory was that the sintered regolith would be brittle, and weaker in tension (pulling apart) than compression (pushing together). It’s also expected to be very thermally insulative, so even a direct blast from the retrorocket of a Starship would only dramatically heat up the top 8cm of a slab. However, this results in cracking each time that ship would launch from the pad.

Video visualizing the design and construction of a lunar landing pad. Credit - Exploration Architecture YouTube ChannelBut the act of landing/ascending isn’t the only major stress the pad would undergo. It would also be affected by the 28 day lunar day/night cycle, where temperatures would vary wildly. The expansion and contraction that the pad would undergo during that cycle would be resisted by friction with the loose regolith soil underneath it - another mechanical property that we don’t understand. The authors do understand that, if temperature changes aren’t spread evenly throughout the slab thickness, the expansion of the hot layer could cause the entirely slab to curl, creating a warping stress that could lead to fracturing.

Taking these behaviors into account, the team suggests that, for a 50 ton lander, the pad should be about ⅓ of a meter thick (or 14 inches for the Imperially inclined). When asked why not simply make it thicker than that to give a sufficient margin of error, Dr. Dyke pointed out in an interview with UT that increasing the depth would make it more likely to fracture under thermal stresses, actually causing the pad to fail more quickly than a smaller version.

There are some failure modes that are expected to happen, though. Spalling is one. In this process, chips of the pad crack off due to the thermal expansion/contraction. While the pad can be designed to maintain its overall structure integrity, over time, with repeated rocket blasts, this could degrade the structural integrity of the pad, causing it to be unable to support the same size of rockets.

Isaac Arthus discusses how industrializing the Moon would be a great way to expand further into the solar system.But perhaps the biggest concern is the fracturing of the pad itself. This could be caused by thermal stresses, spalling degrading its integrity, or even a rocket coming down at a bad angle. Uncertainties crop up in the design process at almost every turn, which is why Dr. Dyke and her co-authors suggest a simple plan for proving the pad will work – in situ testing.

Most likely, the first step of lunar exploration will not be to build a pad for consistent rocket landings/launches. Early missions could collect more data on the material to be used for the pad, and are especially well-placed to do in-situ testing under lunar gravity and atmospheric conditions that are hard to reproduce here on Earth. Once a landing pad is finally in place, instrumenting it and taking data will help improve the design over time. Dr. Dyke is most interested in how the pad is deforming under load, but also during the extreme thermal day/night cycles. With that knowledge, she could predict how cracks would form, and potentially come up with a mitigation strategy in advance.

Mitigating those cracks, and building the pad more generally, will likely be the purview of robots - either teleoperated or completely autonomous. Trying to build such a pad using human labor, especially when that human is enveloped in a bulky space suit that is the only thing keeping them alive in the vacuum of space, is infeasible. So, according to Dr. Dyke, robots will be an absolutely critical part of the equation for building the landing pad - and maintaining it once it is already built.

That first build is probably still years away at this point, as NASA and other agencies are still actively working on getting astronauts back to the Moon. As that process continues, hopefully engineers back on Earth will get some more data to improve their models about how a landing pad might work on the Moon. But even if they don’t, the iterative testing, learning, and design process suggested in the paper could eventually result in a structurally sound, and therefore safe, entry point to our nearest interplanetary neighbor.

Learn More:

E. Mount et al - Lunar Landing and Launching Pad Design Considerations Using ISRU Materials

UT - Lunar Landing Pads Will Need to be Tough

Universe Today

Universe Today