The Lambda Cold Dark Matter (Lambda CDM) model is the current cosmological model and explains much of what we see in the cosmos. One of Lambda CDM's core features is the prediction that structure grows hierarchically from the bottom up. It begins with dark matter density fluctuations, then dwarf galaxies form, then those dwarfs merge to form more massive galaxies, which merge into still larger galaxies. Eventually, there are galaxy clusters.

In this view, dwarf galaxies are the smallest coherent structures, and are the building blocks for larger structures. They merge into progressively larger galaxies and on it goes. But finding evidence of dwarf galaxy mergers has been difficult.

Recent research in The Astrophysical Journal Letters presents evidence of a dwarf galaxy merger on the outskirts of the Milky Way. It's titled "The Extended Stellar Distribution in the Outskirts of the Ursa Minor Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy," and the lead author is Kyosuke Sato. Sato is from the Astronomical Science Program at the Graduate University for Advanced Studies in Tokyo.

"Within this framework (Lambda CDM), dwarf galaxies are among the first systems to form and represent the smallest building blocks in hierarchical clustering," Sato and his co-authors write. "Some of these dwarfs are thought to be the surviving relics of the earliest galaxies. Because the chemical abundances of their stars preserve information from the first billion years of cosmic history, dwarf galaxies serve as key probes for studying galaxy formation in the early Universe."

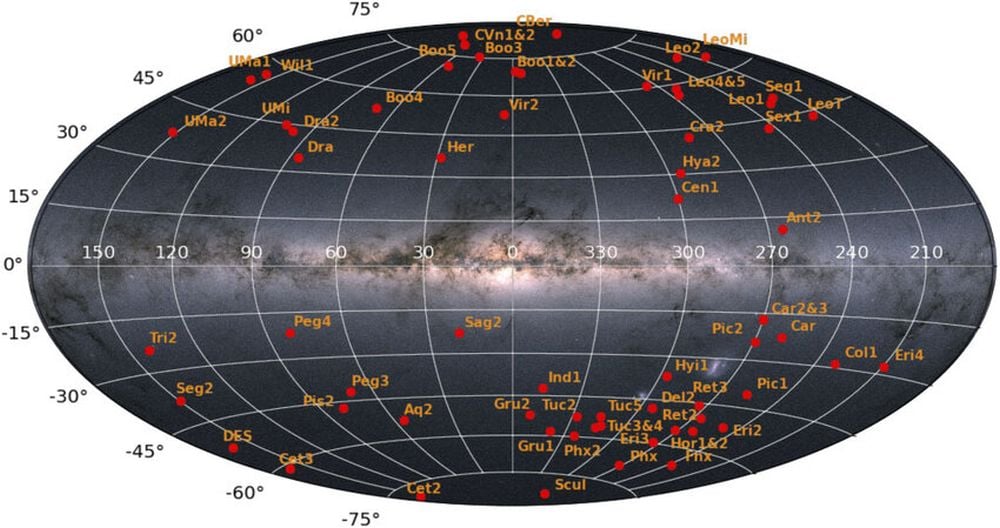

*This image shows many of the Milky Way's dwarf galaxy satellites. UMi dSph is in the upper left, labelled as UMi. Image Credit: ESA/ Gaia /DPAC*

*This image shows many of the Milky Way's dwarf galaxy satellites. UMi dSph is in the upper left, labelled as UMi. Image Credit: ESA/ Gaia /DPAC*

Dwarf galaxies are sometimes called 'fossil galaxies' because they've survived so long and represent the earliest stages of galaxy evolution. There are at least 50 of them in the Milky Way's halo, and likely many more; they can be challenging to detect. From the perspective of Lambda CDM, these dwarf galaxies are evidence of hierarchical structure. Evidence of galaxy mergers are found in the haloes of large galaxies. Could the haloes of dwarf galaxies also contain evidence of the hierarchical structure?

"The remnants of past accreted systems are discovered as substructures in the MW halo," the authors explain. "Detecting and characterizing stellar halos in dwarf galaxies are crucial for understanding whether hierarchical merging processes were also active in low-mass galaxies. Several studies have reported extended stellar distributions around several Local Group dwarf galaxies and are considered to be candidates of stellar halos of dwarf galaxies."

The authors say they've found another extended stellar distribution in the halo around the Ursa Minor dwarf spheroidal galaxy (UMi dSph), one of the Milky Way's satellite dwarfs. UMi dSph is about 225,000 light-years from Earth, and seems to be comprised of older stars and exhibits no star formation, or very little at best. Previous research shows that it was formed in one epic episode of star-birth that lasted for about 2 billion years. Research also shows that it's probably as old as the Milky Way.

*The Ursa Minor Dwarf Spheroidal galaxy is about 225,000 light-years away and is about the same age as the Milky Way. Image Credit: By Giuseppe Donatiello from Oria (Brindisi), Italy - Ursa Minor Dwarf, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71674912*

*The Ursa Minor Dwarf Spheroidal galaxy is about 225,000 light-years away and is about the same age as the Milky Way. Image Credit: By Giuseppe Donatiello from Oria (Brindisi), Italy - Ursa Minor Dwarf, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71674912*

Finding extended structures in a galaxy's halo are evidence of past interactions and mergers. Even a few out of place stars can provide evidence. But stars in a dwarf galaxy's outer regions don't provide much light for observations, limiting previous attempts to find merger evidence. In this work, the researchers used the Subaru Telescope’s wide-field camera to take a closer look at UMi dSph, long considered a candidate for a recent merger event.

"The Ursa Minor (UMi) dwarf spheroidal galaxy (dSph) is a strong candidate for having a stellar halo despite being the lowest-stellar-mass galaxy among the classical dSphs," the researchers explain. Research from 2023 found five candidate stars that are beyond UMi dSph's tidal radius. But five isn't very many, and they were all RGB stars. More evidence was needed before researchers could conclude that the dwarf showed signs of a merger, and the team's observations with the Subaru Telescope found far more main sequence stars in the dwarf's halo.

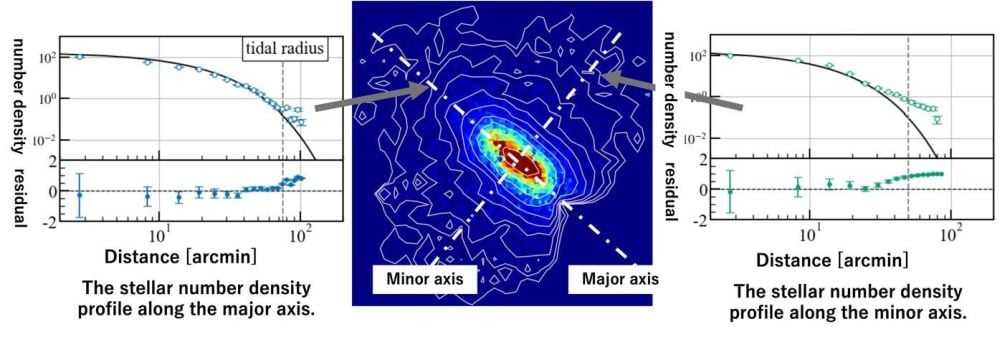

UMi dSph is known to have a major axis, like other galaxies. But with their observations, Sato and his colleagues found another axis, a minor axis. While the major axis corresponds to the dwarf galaxy's orbit around the far more massive Milky Way, the minor axis has a different orientation.

This figure from the research illustrates the minor axis of main-sequence stars in UMi dSph (center). The left and right panels show stellar density along the major (left) and minor (right) axes. The black curves in the side panels show the predicted number density profiles assuming no extended stellar structure. The observed number densities (blue and green points) exceed these predictions along both the major and minor axes, indicating the presence of an extended stellar structure in the outskirts. Image Credit: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

This figure from the research illustrates the minor axis of main-sequence stars in UMi dSph (center). The left and right panels show stellar density along the major (left) and minor (right) axes. The black curves in the side panels show the predicted number density profiles assuming no extended stellar structure. The observed number densities (blue and green points) exceed these predictions along both the major and minor axes, indicating the presence of an extended stellar structure in the outskirts. Image Credit: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

According to the researchers, the minor axis population of main sequence stars is evidence of past merger activity between UMi dSph and another dwarf galaxy.

"We have rarely found evidence of galaxy mergers in the Milky Way’s dwarf galaxies," lead author Sato said in a press release. "This discovery offers a new way of thinking about how dwarf galaxies formed."

The discovery is bolstered by N-body simulations from other research. N-body simulations are a critical tool in astronomy that allow scientists to model large, complex systems with millions or billions of particles. In this case, the particles are individual stars.

"This extended stellar distribution not along the orbit is reproduced by some N-body simulations of a dwarf–dwarf merger," the authors write.

The finding is intriguing but the authors explain that it's not yet conclusive evidence of dwarf-dwarf mergers. The stellar distribution could still be related to tidal interactions with the Milky Way.

"The origin of extended stellar structures in dwarf galaxies remains a topic of active debate," the researchers write. "Some of MW dSphs and UFDs (Ultra-Faint Dwarfs) exhibit extended stellar distribution well beyond their nominal tidal radii. Such structures may result from tidal distortion by the MW, whereby tidal forces strip stars from the galaxy, especially during close pericentric passage."

More probing observations of the stellar kinematics and metallicity will shed more light on the nature of UMi dSph's stellar structure.

"While tidal distortion may have contributed to the formation of this extended structure, we consider that a past merger event could also be a plausible origin," the authors write. "To confirm the existence of this outskirt structure, photometric studies of the more outer regions and chemodynamical analyses are essential," they conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today

](/article_images/eso1914a_20260128_170032.jpg)