White dwarfs are called stellar remnants because they're what's left of main sequence stars after they've shed most of their mass and ceased fusion. But despite being mere remnants for whom fusion is only a distant memory, they can still be the locations of enormously powerful thermonuclear explosions called novae.

White dwarfs are extremely dense and hot cores of what were once stars. They glow with residual heat only, and it can take billions of years for them to cool completely. A nova explosion can only occur in a binary system where one of the stars is a white dwarf. These dense objects draw hydrogen from their companion stars, which accumulates on the white dwarf's surface. The white dwarf heats this material until it triggers a runaway fusion explosion. Sometimes, the white dwarf can be completely destroyed, and those cases are called Type 1a supernova. But most novae are not destructive.

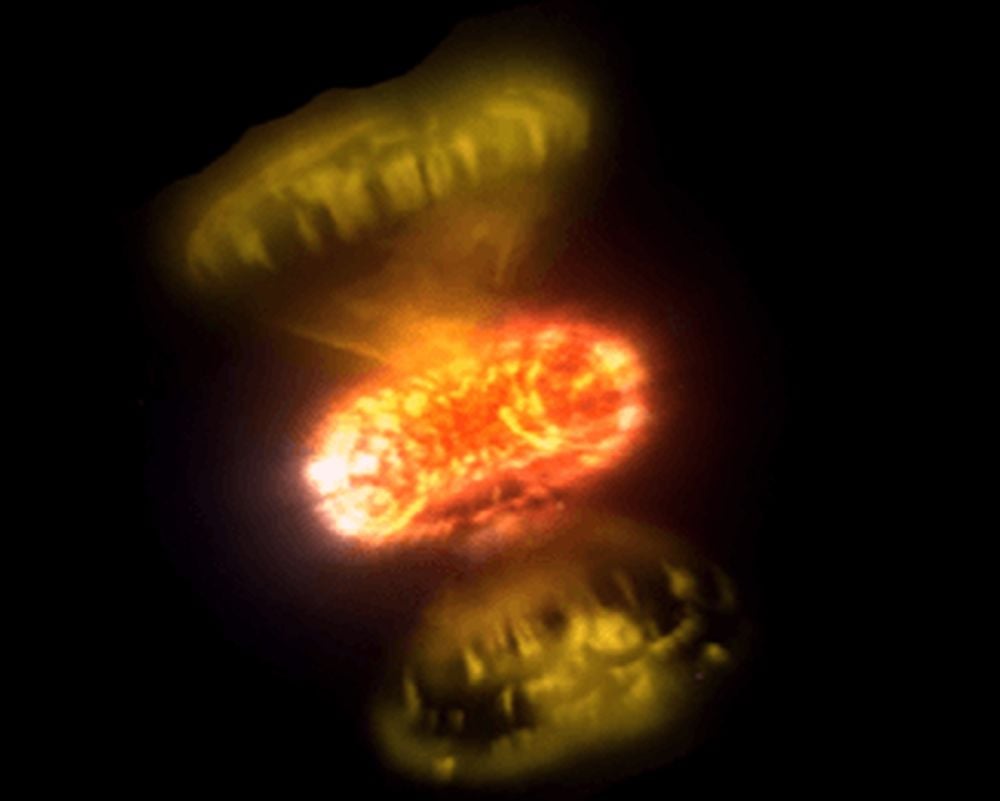

Instead, they eject their accreted envelopes out into space in nova explosions. Astronomers captured detailed images of two different novae that reveal the complexity in these events. Their results are published in a new research article in Nature Astronomy. It's titled "Multiple outflows and delayed ejections revealed by early imaging of novae," and the lead author is Elias Aydi, a professor of physics and astronomy at Texas Tech University.

“These observations allow us to watch a stellar explosion in real time." Elias Aydi, Texas Tech University

"Novae are thermonuclear eruptions on accreting white dwarfs in interacting binaries," the authors write. "Although most of the accreted envelope is expelled, the mechanism—impulsive ejection, multiple outflows or prolonged winds, or a common-envelope interaction—remains uncertain." The authors say that astrophysicists have detected gigaelectronvolt gamma ray emissions from more than 20 novae, and that novae are like nearby laboratories where astrophysicists can study shock physics and particle acceleration, and how novae eject their envelopes.

"The formation mechanisms of the energetic shocks that lead to the GeV γ-ray emission from novae are still poorly constrained," the authors explain. Recent work suggests that the shocks are internal to the ejecta, at the interface of at least two ejections, maybe more. The interacting flows create the shocks, which are responsible for accelerating particles and creating high-energy gamma-ray emissions.

To understand how they eject their envelopes, the authors report on two novae known for their gamma-ray emissions.

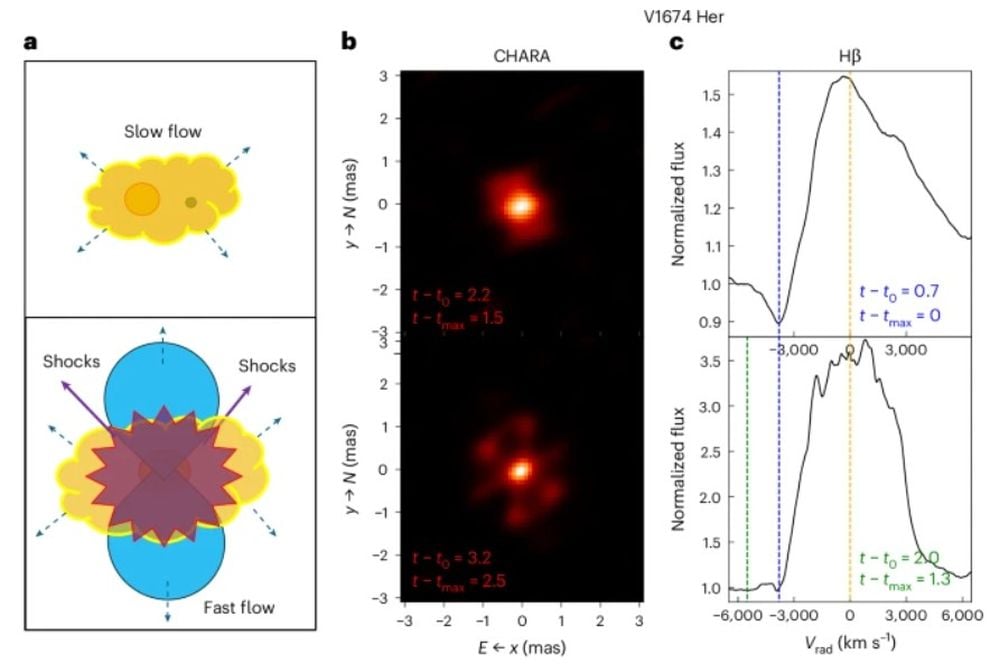

One is V1674 Her, a fast nova from 2021. The other is the slow nova V1405 Cas, also from 2021. V1674 Her is called a fast nova because images captured just 2-3 days after the explosion show material being expelled in two perpendicular outflows, evidence of multiple interacting ejections. It's among the fastest novae known, flaring brightly then fading away in only a few days.

*These figures from the study illustrate how V 1674 Her experienced multiple explosions in rapid succession. (a) shows how a slow explosion first expelled material, then a second faster explosion expelled more material that slammed into the existing material, generating shocks and gamma-ray radiation. (b) are CHARA images showing the nova explosion at 2.2 and 3.2 days after it V 1674 Her was discovered. (c) shows Hβ (H-beta) spectral line profiles for hydrogen atoms. Image Credit: Aydi et al. 2025. NatAstr*

*These figures from the study illustrate how V 1674 Her experienced multiple explosions in rapid succession. (a) shows how a slow explosion first expelled material, then a second faster explosion expelled more material that slammed into the existing material, generating shocks and gamma-ray radiation. (b) are CHARA images showing the nova explosion at 2.2 and 3.2 days after it V 1674 Her was discovered. (c) shows Hβ (H-beta) spectral line profiles for hydrogen atoms. Image Credit: Aydi et al. 2025. NatAstr*

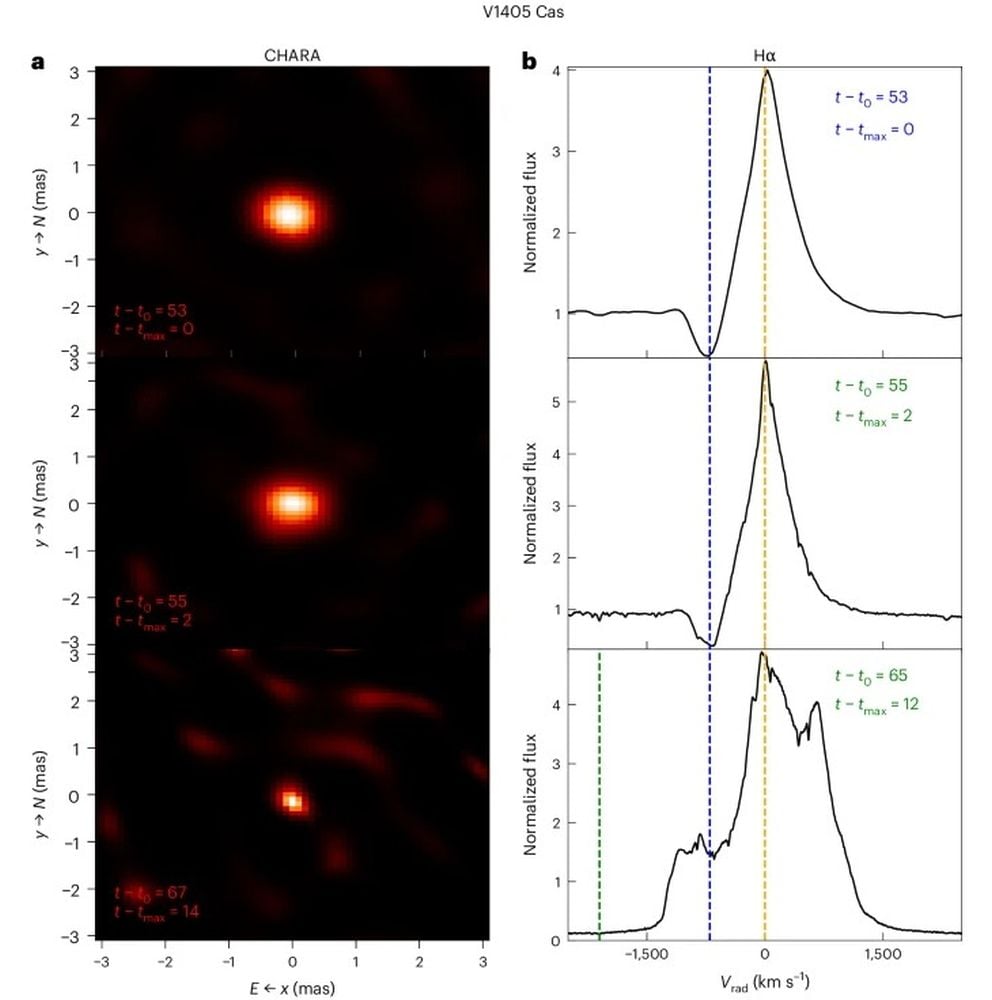

V1405 Cas is called a slow nova because images show that the bulk of the expelled material wasn't apparent until 50 days after the explosion. It's the first evidence of delayed ejection from a nova. When V1405 Cas finally expelled the material, it triggered new shocks that produced more gamma-rays.

“These observations allow us to watch a stellar explosion in real time, something that is very complicated and has long been thought to be extremely challenging,” said lead author Elias Aydi. “Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold. It’s like going from a grainy black-and-white photo to high-definition video.”

“The fact that we can now watch stars explode and immediately see the structure of the material being blasted into space is remarkable." John Monnier, University of Michigan.

The researchers used two types of observations to study the novae: interferometry and spectrometry. For interferometry, they turned to the Georgia State University CHARA (Center for High-Angular Resolution Astronomy) Array. For spectrometry, they used data from other observatories like Gemini. Interferometry let the astronomers uncover fine detail in the explosions, and spectrometry let them identify new chemical fingerprints in the ejecta as it evolved.

But the critical part of it is that the spectra lined up with the structures revealed by the interferometry. This is an important confirmation of how the flows of material were colliding.

“This is an extraordinary leap forward,” said co-author John Monnier, a professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan, and an expert in interferometric imaging. “The fact that we can now watch stars explode and immediately see the structure of the material being blasted into space is remarkable. It opens a new window into some of the most dramatic events in the universe.”

*Early imaging of V1405 Cas shows how the ejection of material was delayed more than 50 days after eruption. CHARA imaged it 53, 55 and 67 after explosion. The H-alpha emissions were measured 53, 55 and 65 days after the explosion. It generated shock waves that also triggered gamma-ray emissions. Image Credit: Aydi et al. 2025. NatAstr*

*Early imaging of V1405 Cas shows how the ejection of material was delayed more than 50 days after eruption. CHARA imaged it 53, 55 and 67 after explosion. The H-alpha emissions were measured 53, 55 and 65 days after the explosion. It generated shock waves that also triggered gamma-ray emissions. Image Credit: Aydi et al. 2025. NatAstr*

Extreme astrophysical environments like nova explosions are important because they define some of Nature's limits. Without understanding those limits, we don't really understand Nature. Because of their shock waves and high-energy gamma-ray emissions, they're natural laboratories for extreme events in the cosmos.

“Novae are more than fireworks in our galaxy — they are laboratories for extreme physics,” said Professor Laura Chomiuk, a co-author from Michigan State University and an expert on stellar explosions. “By seeing how and when the material is ejected, we can finally connect the dots between the nuclear reactions on the star’s surface, the geometry of the ejected material and the high-energy radiation we detect from space.”

Everything about Nature seems to come down to increasing complexity. And that complexity is only revealed as we improve our telescopes and observatories. While scientists once thought that nova explosions were single explosive events, these results show otherwise. There are multiple outflows and delayed ejections, and who knows what else yet to be discovered. These are not simple phenomenon.

“This is just the beginning,” Aydi said. “With more observations like these, we can finally start answering big questions about how stars live, die and affect their surroundings. Novae, once seen as simple explosions, are turning out to be much richer and more fascinating than we imagined.”

Are these two novae outliers? Are there some that are much more simple? The next step in understanding novae is to gather more data.

"By increasing the sample of novae observed with CHARA and other optical and NIR interferometers in the future, we can confirm if this delayed ejection is common in other novae, which would establish novae as ideal laboratories in our Galactic backyard to constrain the physics of common-envelope interaction," the researchers conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today