By its very nature, spaceflight is very challenging and very wasteful. As Tsiolkovsky's famous Rocket Equation establishes, propellant accounts for the majority of a rocket's mass, which is burned off during launch. The process also introduces large amounts of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, water vapor, and black carbon, as well as ozone-depleting chemicals, into the upper atmosphere. On top of that, the disposal process for satellites once they are no longer operational (deorbiting and burning up in the atmosphere) is also wasteful, with no materials retrieved or reused.

And with the rapid growth of commercial launch services and the proliferation of satellite constellations, the situation is only likely to get worse. In a recent paper, a group of sustainability and space scientists addressed this problem and considered how the principles of reducing, reusing, and recycling could be applied to satellites and spacecraft throughout their lifecycles. This means finding ways to eliminate waste during design and manufacturing, launch and deployment, and allowing for in-orbit repair and end-of-life repurposing.

The team was led by Zhilin Yang, a researcher from the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences at the University of Surrey. He was joined by Associate Professor Lirong Liu of the Surrey Center for Environment and Sustainability; Dr. Lei Xing, a Biological Sciences Professor and the Principal Investigator of Xing Lab at the University of Manitoba; and Professor Jin Xuan, the Associate Dean of Research and Innovation at Surrey, and Adam Amara, a Chief Scientist with the UK Space Agency and the Director of Surrey Space Institute (SSI). Their paper, "Resource and material efficiency in the circular space economy," appeared on Dec. 1st, in the journal *Chem Circularity*.

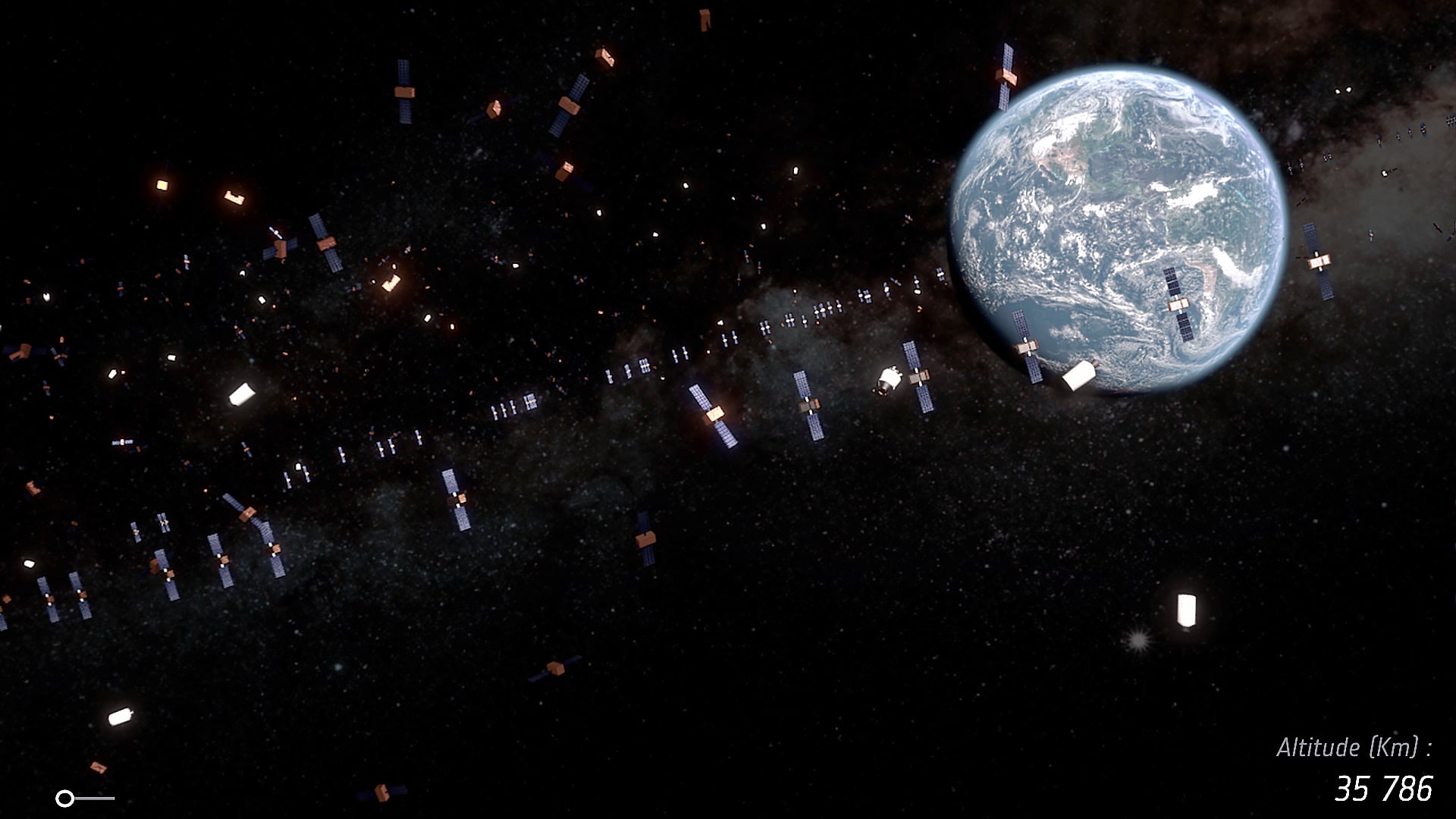

Since 1957, with the launch of Sputnik I (the first artificial satellite launched to space), space agencies worldwide have conducted no less than 7,070 launches (excluding failures). This has created an unsustainable situation in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), characterized by about 15,100 metric tons (16,645 U.S. tons) of objects ranging from more than 10 cm (4 in) in diameter to just a few millimeters. The presence of so much debris in orbit also raises the threat of the Kessler Effect, in which collisions between objects generate more debris, which in turn generates more collisions, and so on in a cascading effect.

This is similar to how our reliance on single-use plastics has created an unsustainable garbage problem, leading to things like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. In addition, the problem of waste is built into the entire life-cycle of rockets, spacecraft, and satellites, beginning with expendable launch systems, single-use satellites, and "graveyard orbits." As the space economy continues to grow, this situation will only grow worse if wasteful practices are not addressed. Said Xuan in a University of Surrey press release:

Each rocket launch sends tonnes of valuable materials into space that are never recovered. To make the space economy truly sustainable, we need to build circular thinking into missions from the very start - from how we design and manufacture spacecraft to how we operate and retire them. That means developing systems that can be refueled, repaired, or reconfigured in orbit, and materials that can be recovered and recycled rather than lost.

The only solution, according to space sustainability and environmental researchers, is to transition to a circular space economy in which materials and systems are designed with reuse, repair, or recycling in mind. As the authors note, advances in chemistry, materials science, and artificial intelligence could help make this happen, including self-repairing materials and digital twin simulations that reduce the need for physical testing. The authors also point to lessons from other industries that are already implementing changes to become more sustainable.

Primary sources of space debris: fragmentation events (65%), decommissioned spacecraft and rocket bodies (30%), and mission-related objects (5%). Credit. Credit: Yang et al. (2025)

Primary sources of space debris: fragmentation events (65%), decommissioned spacecraft and rocket bodies (30%), and mission-related objects (5%). Credit. Credit: Yang et al. (2025)

These include the electronics industry and the automotive sector, which have been plagued by issues of e-waste and "conflict metals," as well as problems disposing of broken-down models. Whereas the former has developed methods to recover precious metals, the latter has demonstrated that repairing and remanufacturing components can extend vehicle lifespans. There is also the sanitation industry, where the principles of reduce, reuse, and recycle (the 3 Rs) were first developed to reduce the amount of waste that average households produce and lessen our impact on the natural environment.

To reduce waste, they advise that the space sector increase the durability of spacecraft and satellites and produce designs that can be repaired more readily. They also recommend reducing the number of launches by repurposing space stations as hubs for refueling and repairing spacecraft, and/or manufacturing satellite components. This strategy is one that NASA has been pursuing with its NASA Exploration & In-space Services (NExIS) program, which developed a technology demonstrator known as the On-orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing-1 (OSAM-1) mission.

Commercial space companies like Arkisys and Orbit Fab are also working to build orbital platforms that could refuel and refurbish satellites, greatly extending their service lives. Xuan and his team further advocate for the creation of reusable or recyclable space stations through soft-landing systems, parachutes, and airbags. This way, rather than simply burning up in the atmosphere at the end of their service life, stations could land after entering Earth's atmosphere, and their components retrieved (pending rigorous safety tests, of course).

The authors also recommend that orbital debris be recovered using nets or robotic arms, so that their materials can be recycled. There are many efforts underway to develop spacecraft that could deorbit defunct satellites and larger pieces of debris. These same spacecraft could be adapted to haul debris to orbital facilities where they could be used to fashion new building materials or replacement parts for satellites in need of servicing. Last, but not least, is the important role that emerging AI technologies will play, such as informing designs based on spacecraft data and using simulations to reduce reliance on physical testing. Said Xuan:

We need innovation at every level, from materials that can be reused or recycled in orbit and modular spacecraft that can be upgraded instead of discarded, to data systems that track how hardware ages in space. But just as importantly, we need international collaboration and policy frameworks to encourage reuse and recovery beyond Earth. The next phase is about connecting chemistry, design, and governance to turn sustainability into the default model for space.

Further Reading: University of Surrey, Cell Press

Universe Today

Universe Today