Long before scientists discovered that other stars in the Universe host their own planetary systems, humanity had contemplated the existence of life beyond Earth. As our technology matured and we began monitoring the night sky in multiple wavelengths (i.e., radio waves), this curiosity became a genuine scientific pursuit. By the 1960s, a scientific field dedicated to the search for advanced life (similar to ours) emerged: the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). Since then, multiple SETI surveys have been conducted to search for potential signs of technological activity (aka. "technosignatures").

To date, the majority of these searches have looked for signs of possible radio transmissions, including the most ambitious SETI project to date - Breakthrough Listen. Other surveys have included looking for thermal emissions that could be alien megastructures. So far, these searches have failed to find decisive evidence of technosignatures or advanced life. According to a new study led by the School of Earth and Space Exploration (SESE) at Arizona State University (ASU), humanity's SETI efforts to date may have been constrained by anthropocentric bias.

The team also included researchers from ASU's Beyond Center, the School of Complex Adaptive Systems (SCAS), and the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society. Additional contributions were made by scientists from the Santa Fe Institute, the BioFrontiers Institute, and various departments of the University of Colorado. The paper describing their findings is being reviewed for publication in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Nexus.

"Like Ourselves"

As the team notes in their paper, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) has been a search for the familiar. In essence, we have been looking for signals and technosignatures that mirror our current stage of technological development. For instance, Project Ozma was informed by humanity's own development of radio communications, which by the 1960s had progressed to the point that our signals could be detected from space. This approach is not without merit, since radio signals can be transmitted over vast cosmic distances.

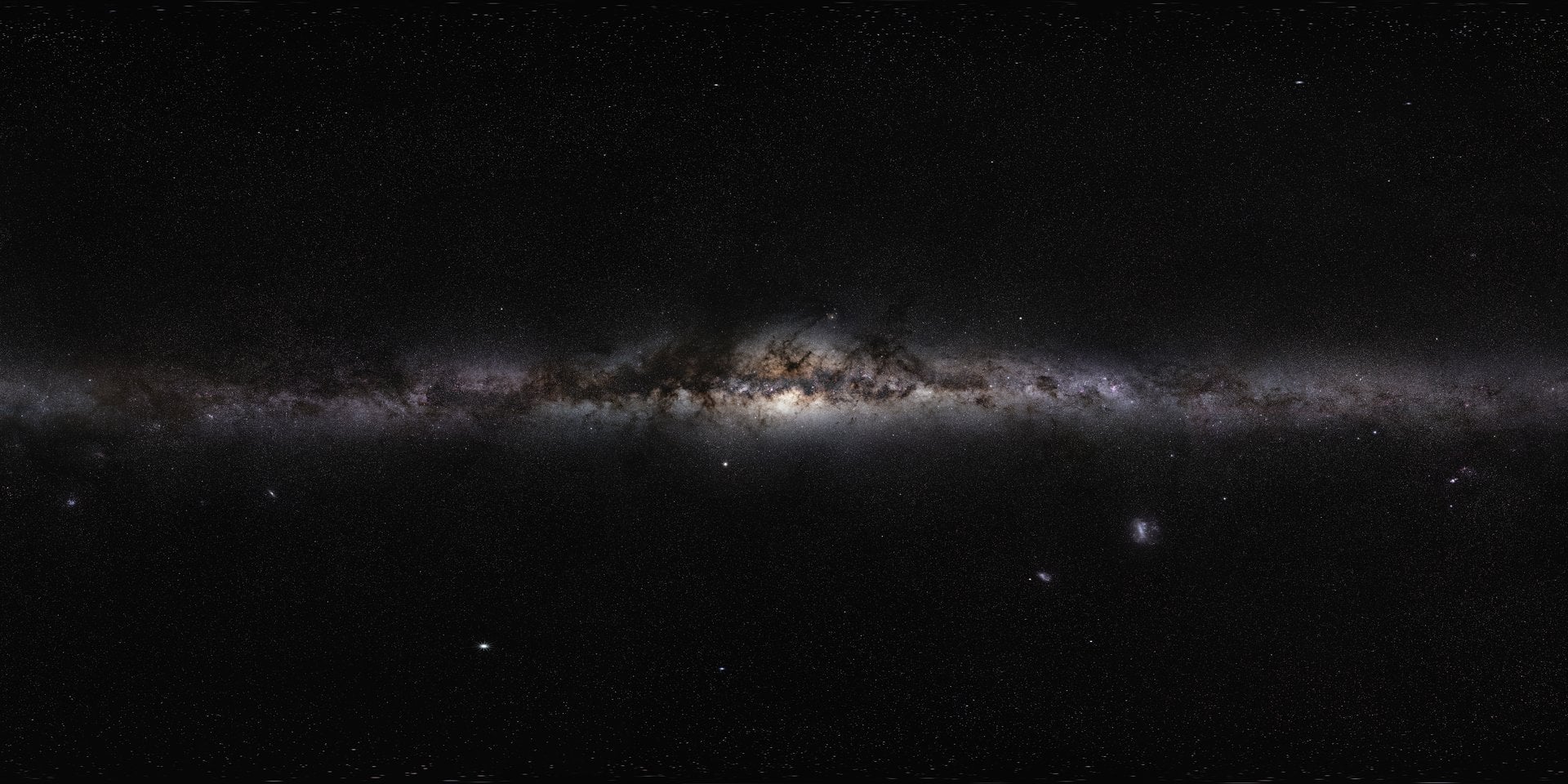

*The plane of our Milky Way Galaxy, which we see edge-on from our perspective on Earth, cuts a luminous swath across the image. Credit: ESO/S. Brunier*

*The plane of our Milky Way Galaxy, which we see edge-on from our perspective on Earth, cuts a luminous swath across the image. Credit: ESO/S. Brunier*

However, Earth has become less "radio loud" over subsequent decades, thanks to the development of satellite communications, the internet, and other transmission technologies that do not rely on radio. Ergo, searching for radio transmissions is tantamount to looking for evidence of advanced civilizations during a brief window of technological development. In recent years, SETI researchers have expanded the possible range of technosignatures to include optical transmissions (lasers), neutrinos, gravitational waves (GWs), and other exotic ideas.

Alas, our efforts are still hampered by the fact that we have no prior knowledge of what to look for. "SETI has traditionally spanned two extremes: an anthropocentric search for human-like technosignatures and an anomaly-based search for signals that deviate from known astrophysics," explained co-author and SESE PhD candidate Estelle Janin to Universe Today via email. "Because we don’t know whether intelligence is likely to look familiar or inherently 'weird,' the field needs stronger theoretical frameworks that identify generalizable features of life and intelligent communication without requiring either complete prior knowledge or no assumptions at all."

As an alternative approach, she and her team recommend broadening the search to include non-human species and their respective communication methods. As they explain, the primary focus of both SETI and the emerging field of Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence (METI) is the identification of signals that could be universally understood. Specifically, the team used firefly communication patterns, which consist of evolved flashes that are distinct from their visual backgrounds. This broadening of perspective also addresses another ongoing problem in SETI research: the way "intelligence" is poorly constrained. Said Janin:

Communication is a fundamental feature of life across lineages and manifests in a wonderful diversity of forms and strategies. Taking non-human communication into account is essential if we want to broaden our intuition and understanding about what alien communication could look like, and what a theory of life ought to explain. It also keeps the search empirically grounded: rather than relying solely on undefined anomalies, we can start from what life on Earth demonstrably does—not restricted to humans—and ask which aspects might reflect more universal, generalizable regularities, based on evolution and selection.

Methods

As they summarize in their paper, fireflies produce periodic flash sequences during their mating season that are species-specific. When multiple species of fireflies are present in the same location at the same time, their flash patterns allow fellow members to distinguish between other species while minimizing the risk of predation. Their study builds on the firefly communication model that simulates the evolution of firefly flash sequences over several generations. They then examined how such signaling might influence the detectability of an extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) against the background of space.

*Hubble's "Cosmic Fireflies," a rich cluster of galaxies called Abell 2163. Credit: NASA/ESA/STScI*

*Hubble's "Cosmic Fireflies," a rich cluster of galaxies called Abell 2163. Credit: NASA/ESA/STScI*

They also developed a model of their own that generated an evolved signal distinct from a background of naturally occurring pulsar signals. The signal that resulted minimized energy consumption in a way that mimics how firefly flash patterns maximize distinctiveness while minimizing the risk of attracting predators. The team selected pulsars because they are common throughout our galaxy and produce highly ordered emissions at regular intervals. This is why, when they were first discovered in 1967, many in the astronomical community thought they might constitute transmissions from an ETI, and why many today consider them as viable "navigational beacons."

They were further chosen because pulsars provide an appropriate analog for firefly flash behavior, and they offer a practical and observable backdrop against which ETI signals could be distinguished. In this respect, their approach preserves the strategy of looking for life "like ourselves," but expands what that means by examining communication across the entirety of Earth's biosphere. It also takes advantage of advancements made in the study of animal communication and digital bioacoustics, said Janin, which have yet to be applied to SETI and life detection efforts:

Our study is meant as a provoking thought-experiment and an invitation for SETI and animal communication research to engage more directly and to draw more systematically on each other’s insights. More broadly, remote-sensing astrobiology has often struggled to keep pace with progress in biology, particularly when it comes to appreciating and integrating the full diversity of Earth’s living systems, and has tended to focus more on issues related to the nature of astrophysical data rather than on the properties of life it seeks to infer.

Results

Their model consisted of a background of 158 pulsars within a 5 kiloparsec (~16,300 light-year) search area centered on Earth. The pulsars were generated using data from the Australia National Telescope Facility (ATNF) database. They then added artificial signals modulated based on different relationships between dissimilarity and energy costs. Both the "pulse" and "flash" profiles were grouped based on on/off states, with a mean flux density used as the cutoff. They ran multiple permutations in this setup, accounting for different energy levels.

Their results showed that most of the pulsar population have energy costs that are much higher (~84% to 99.78%) than that of the optimized artificial signals. Their model also incorporated energy constraints alongside dissimilarity, enabling them to compare how each influences the structure of the output sequence. As Janin summarized:

We show that alien signals don’t have to be complicated or semantically decipherable to be recognized; rather, their inherent structure can be identified as a product of selection and evolution, uniquely and robustly implying the presence of life. This approach challenges SETI to consider the broader Earth biosphere and to adopt less anthropocentric methods, grounded in the ubiquitous structural properties of life and communication.

*The Milky Way Galaxy seen over the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array west of Socorro, New Mexico. Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF/Jeff Hellerman*

*The Milky Way Galaxy seen over the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array west of Socorro, New Mexico. Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF/Jeff Hellerman*

The research is part of a growing chorus dedicated to expanding the scope of SETI to include more exotic technologies, life forms, and forms of communication. As the technology and instruments for SETI become increasingly sophisticated, the possible frameworks (i.e., what we should be looking for) are growing accordingly. In the not-too-distant future, there could be SETI projects dedicated to looking for "spillover from directed-energy propulsion and communications, quantum communications, and neutrino signals using everything from radio antennas and infrared telescopes to Solar Gravitational Lenses.

"Studying non-human signaling can keep SETI empirically grounded while expanding our expectations for what alien communication might look like," said Janin. "Using firefly flashes as an example of signals evolutionary optimized to stand out from their environmental background, we argue that SETI should engage more deeply with animal communication and digital bioacoustics—fields that have rapidly advanced but remain under-connected to life-detection efforts."

Further Reading: arXiv

Universe Today

Universe Today