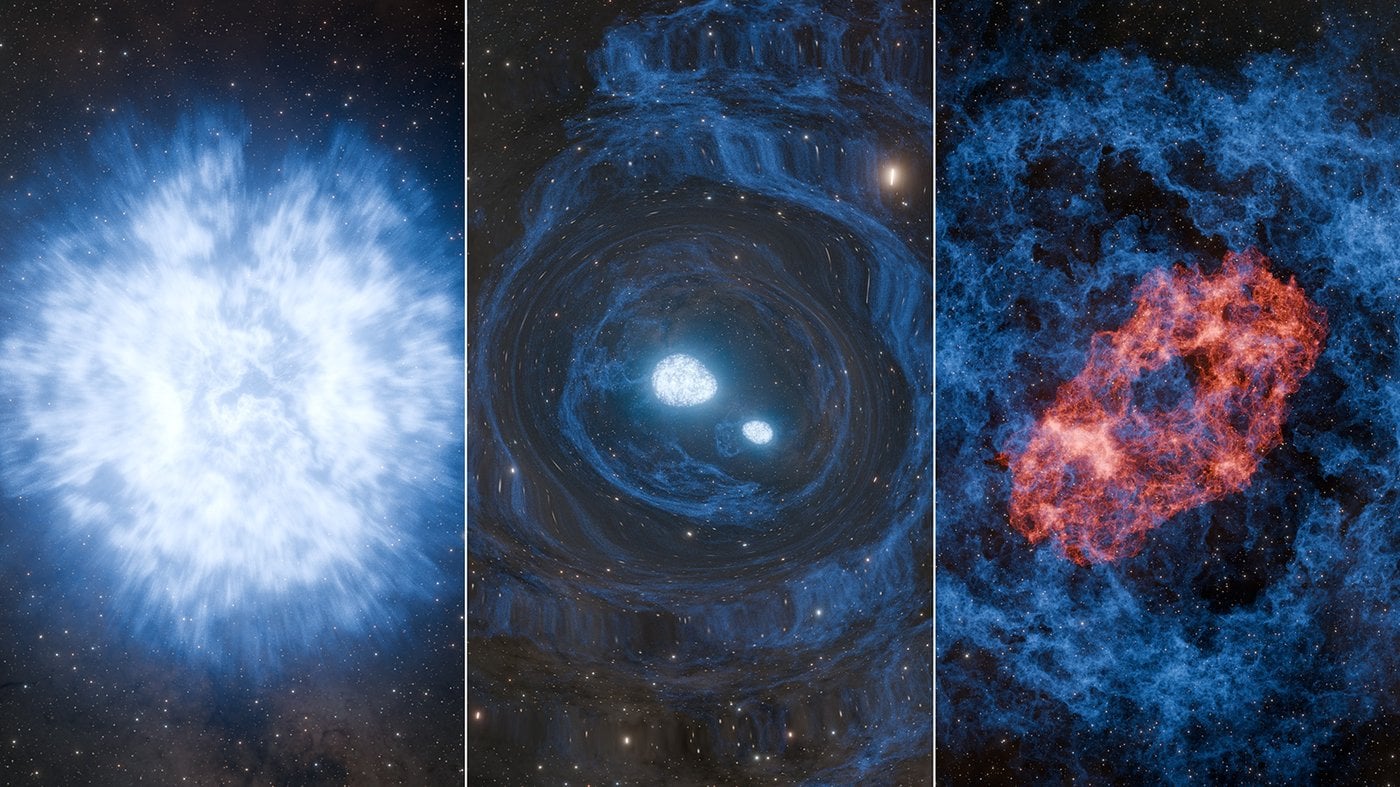

Astronomers may have just seen the first ever ‘superkilonova,’ a combination of a supernova and a kilonova. These are two very different kinds of stellar explosions, and if this discovery stands, it could change the way scientists understand stellar birth and death.

When a massive star dies, astronomers call the resulting violent thermonuclear explosion a supernova. These dramatic deaths leave behind a remnant, where the core of the old star forms a densely packed neutron star, or even a black hole if there is enough mass. Supernovas are very common events in the universe. Astronomers regularly see them popping off, observing something like 20,000 of them every year.

A much rarer event is the kilonova, with only one confirmed event on record, captured in 2017. Dimmer than a supernova, but more visible in gravitational wave data, these explosions are the result of two neutron stars colliding. They are believed to be the primary source of heavy elements in the universe, including platinum and uranium.

A team of researchers now believe they have seen a supernova followed by a kilonova mere hours later from the same source, sparking questions about how both events could be related.

The potential ‘superkilonova’ took place on August 18th, 2025, and was first detected by the Laser Interferometry Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO). Given the name AT2025ulz, the event closely resembled the gravitational wave signals produced by the 2017 kilonova event.

Notified by LIGO, other telescopes that observe using electromagnetic signals (visible light, x-rays, infrared, and radio) quickly turned to observe the aftermath.

"At first, for about three days, the eruption looked just like the first kilonova in 2017," says Mansi Kasliwal, director of Caltech's Palomar Observatory, in a press release. "Everybody was intensely trying to observe and analyze it, but then it started to look more like a supernova, and some astronomers lost interest. Not us."

What Kasliwal’s team saw was an initially strong signal in red wavelengths, evidence of the presence of heavy elements you’d expect to find after a kilonova. However, over time, the signal brightened and turned blue, and appeared to show hydrogen gas, all of which suggests a supernova.

This puzzle is not yet solved, but Kasliwal’s team have offered a plausible theory that might explain what’s going on.

Perhaps when the star that triggered AT2025ulz went supernova, it left behind not one core, but two. These tiny twin neutron stars subsequently collided, resulting in the double superkilonova explosion.

There are a couple ways this might have happened, but both of them require that the initial parent star be spinning rapidly. In one scenario, after the supernova goes off, the core is split into two neutron stars via a process called fission. In the second, a single neutron star forms with a disk of material around it. This disk later clumps into a small neutron star, in a process very similar to planet formation in a solar system.

For the moment, both these theories are unproven. Neutrons stars that small have never been seen before (though this doesn’t rule out their existence), and it’s even possible that the gravitational wave event and the subsequent electromagnetically-observed supernova were from two different, but nearby, sources.

“We do not know with certainty that we found a superkilonova, but the event nevertheless is eye opening,” Kasliwal says.

The only surefire way to confirm that a superkilonova happened is to keep watching for similar events in future, and after AT2025ulz, the astronomical community is sure to keep their eyes open for more.

This research was published on December 15th in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Universe Today

Universe Today