The early Universe was a busy place. As the infant cosmos exanded, that epoch saw the massive first stars forming, along with protogalaxies. It turns out those extremely massive early stars were stirring up chemical changes in the first globular clusters, as well. Not only that, many of those monster stars ultimately collapsed as black holes.

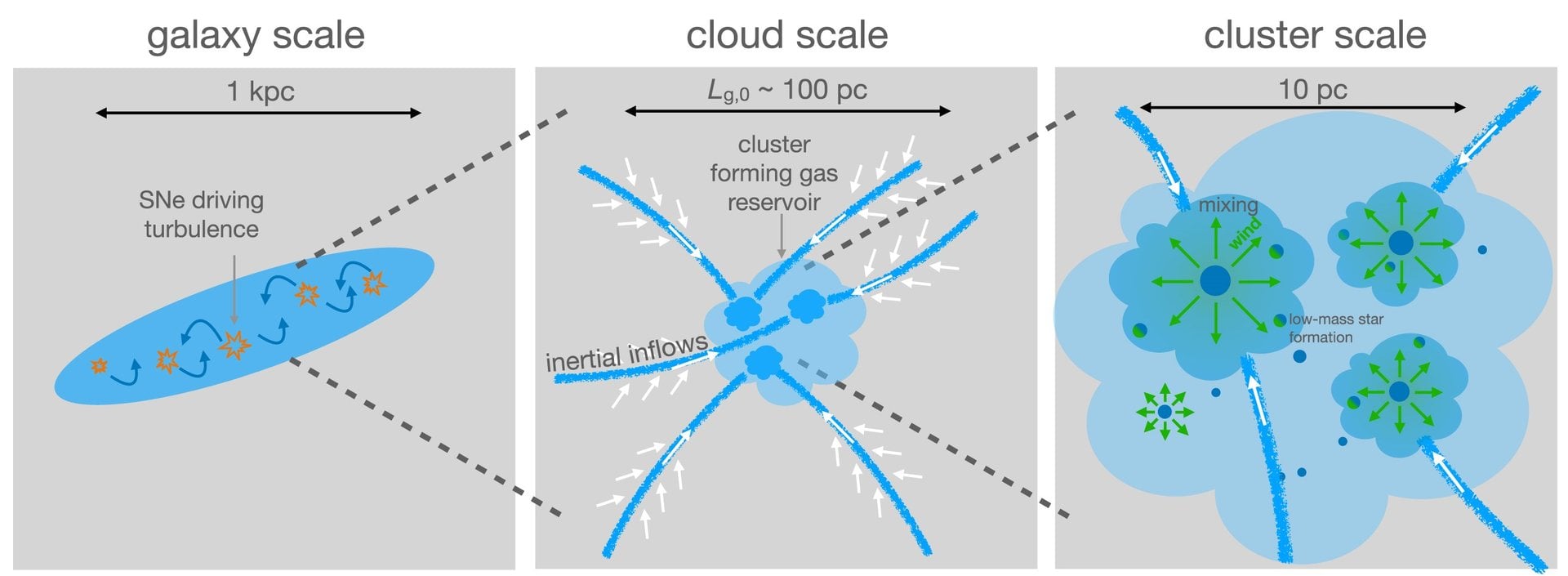

A team led by University of Barcelona researcher Mark Gieles, wanted to understand the role these short-lived stellar giants played in the birth and evolution of the oldest-known star cllusters. So, they developed a model that helped explain how stars with more than a thousand times the mass of the Sun guided cluster evolution in the early Universe. Their simulation, called the "inertial-flow" model describes how stars begin to form by converging flows (inflow) as a result of supersonic turbulence in a region of space. They used their model to explain unusual chemical abundances in those early clusters as a result of those stars.

A schematic view of globular cluster formation. Turbulence driven by supernovae whips up activity in the cluster gases. This leads to formation of extremely massive stars that give off enriched winds into the pristine hydrogen gas environment. Low mass stars also form. Courtesy Gieles, et al.

A schematic view of globular cluster formation. Turbulence driven by supernovae whips up activity in the cluster gases. This leads to formation of extremely massive stars that give off enriched winds into the pristine hydrogen gas environment. Low mass stars also form. Courtesy Gieles, et al.

A Quick Look at Globular Clusters

Globulars are spherical groups of thousands or millions of stars corraled into relatively small regions of space. Most galaxies have them, and the ages of their stars indicate they were born not long after the Big Bang. Some predate the formation of their associated galaxies. The Milky Way has a collection of globulars swarming around its core. Astronomers suspect there could be more than 200, although at least 150 are currently known. Our galaxy is about 13.6 billion years old, and the stars in these globulars are older than that.

An HST image of the metal-poor globular cluster Djorgovski 1. It lies close to the center of the Milky Way Galaxy and due to the chemical makeup of its stars, its formation likely occurred extremely early in our galaxy's history. Courtesy: ESA/Hubble & NASA.

An HST image of the metal-poor globular cluster Djorgovski 1. It lies close to the center of the Milky Way Galaxy and due to the chemical makeup of its stars, its formation likely occurred extremely early in our galaxy's history. Courtesy: ESA/Hubble & NASA.

Other galaxies have them, as well, and astronomers have seen the formation of such clusters as a result of interactions between galaxies. That typically happens as the gravitational influences between the galaxies trigger shock waves in clouds of gas and dust. That sets off the formation of densely packed populations of stars. Most clusters contain low-metal old stars, signifying their formation early in cosmic history when hydrogen was the only (or main) building block of stars.

Chemical Evolution of Early Clusters

The globular clusters in the Giele's study are ancient EMS stars. They should be like other globular cluster stars chemically, but instead, show some puzzling chemical signatures. They feature higher-than expected amounts of helium, nitrogen, oxygen, sodium, magnetsium, and aluminum. These are part of the so-called "heavy elements", meaning chemical substances with higher atomic numbers than hydrogen.

M92 is one of the oldest of the Milky Way's globular clusters. It's stars are generally hydrogen and helium-rich and it likely formed shortly after the Big Bang. Courtesy ESA/Hubble & NASA, Gilles Chapdelaine.

M92 is one of the oldest of the Milky Way's globular clusters. It's stars are generally hydrogen and helium-rich and it likely formed shortly after the Big Bang. Courtesy ESA/Hubble & NASA, Gilles Chapdelaine.

The earliest stars formed from the primordial hydrogen, and the early Universe was primarily hydrogen. The elements heavier than hydrogen are created inside stars, which means that the early massive stars shouldn't have been "contaminated" until some stars started to die and enrich the interstellar medium with elements cooked up in their interiors. So, the assumption is that some kind of activity occurred to "enrich" the cluster environment with heavier elements and that's why Gieles and the team formulated their model. “Our model shows that just a few extremely massive stars can leave a lasting chemical imprint on an entire cluster,” said Gieles. “It finally links the physics of globular cluster formation with the chemical signatures we observe today.”

Essentially, the model shows that in the very massive star clusters that existed way back then, regions with turbulent gas birthed those extremely massive stars. Most were at least a thousand solar masses and some were as much as 10,000 solar masses. Such massive stars did what all stars do: they cooked up elements in their cores via nuclear fusion. As massive stars do, they produced extremely strong stellar winds that enriched the cluster neighborhood with what astronomers call "high-temperature hydr ogen combustion products." They mixed with the predominant hydrogen gas clouds and ultimately, those clouds produced new generations of stars with distinctly different chemical signatures.

Implications for the Milky Way and Beyond

The team's study of these earliest globular clusters provides a pathway that connects star formation physics, cluster evolution, and chemical enrichment in the early Universe. It suggests that EMSs were key drivers of early galaxy formation, simultaneously enriching globular clusters and giving rise to the first black holes. Here's how it could work.?

The model's predictions not only help explain why the Milky Way's clusters are the way they are, but also explain some new findings by the James Webb Space Telescope. It catalogued nitrogen-rich galaxies in the distant Universe. The researchers think that those galaxies also had EMS-rich-globular clusters that formed during the early stages of galaxy formation.

“Extremely massive stars may have played a key role in the formation of the first galaxies,” said Paolo Padoan (Dartmouth College and ICCUB-IEEC). “Their luminosity and chemical production naturally explain the nitrogen-enriched proto-galaxies that we now observe in the early universe with the JWST.”

As with most EMS star collections, those early ones exploded as supernovae. That further enriched their cluster environment and influenced the next generations of stars with even heavier elements. But, that's not all. Those stars likely collapsed to form the first intermediate-mass black holes with total mass of each one to be more than 100 solar masses. If they collide with one another, it's entirely possible that gravitational wave observatories could detect such events in the early Universe.

For More Information

Extremely Massive Stars Forged the Oldest Stars Clusters in the Universe

Universe Today

Universe Today