Everybody knows that galaxies are large structures made of stars. That's a simple definition, and ignores the fact that galaxies also contain gas, dust, planets, moons, comets, asteroids, etc., and of course, dark matter. But one type of galaxy is mostly made of dark matter, and they're difficult to detect.

They're called dark galaxies, and they contain no stars, or only very few stars. Scientists have long theorized about their existence, which has remained hypothetical; they've found galaxies with low surface brightness, and they've found dark galaxy candidates. But new research has found the strongest candidate yet.

The research is "Candidate Dark Galaxy-2: Validation and Analysis of an Almost Dark Galaxy in the Perseus Cluster" and it's published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The lead author is Dayi (David) Li, a post-doctoral fellow in statistics and astrophysics at the University of Toronto.

The candidate galaxy has been dubbed CDG-2, for Candidate Dark Galaxy 2. (CDG-1 is explained here.) CDG-2 is in the Perseus galaxy cluster about 300 million light-years away. The obvious question is, if it's so dark how was it detected?

It comes down to globular clusters (GC). Most galaxies have GCs. They're spherical groups of stars that are bound together gravitationally and can contain millions of stars. Around spiral galaxies like ours, they're mostly found in the galactic halo. Their origins are unclear, as is the role they play in the evolution of galaxies.

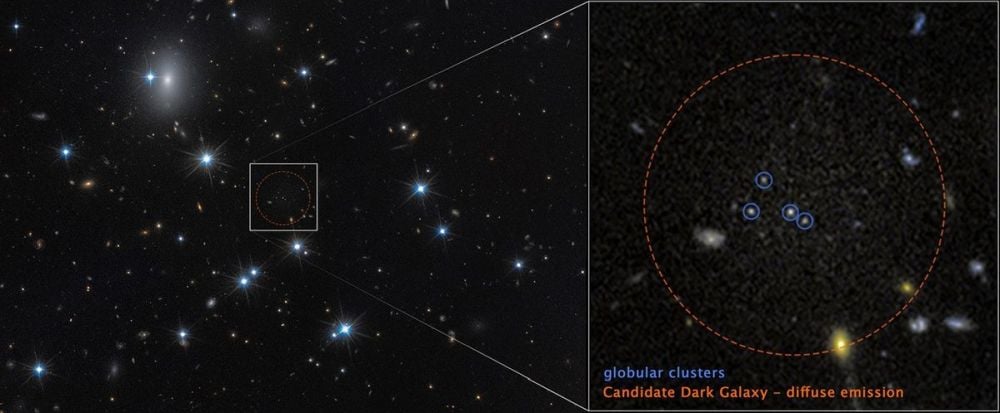

In this work, the researchers used the Hubble, the ESA's Euclid space telescope, and Japan's Subaru telescope. They searched for tight groupings of GCs that could indicate the presence of a galaxy. The Hubble found four closely-connected GCs in the Perseus cluster. The researchers then applied advanced statistical methods on data from the three telescopes that revealed a faint glow around the GCs. This glow is a strong indication that there's an underlying galaxy whose individual stars are too dim to resolve.

“This is the first galaxy detected solely through its globular cluster population,” lead author Li said in a press release. “Under conservative assumptions, the four clusters represent the entire globular cluster population of CDG-2.”

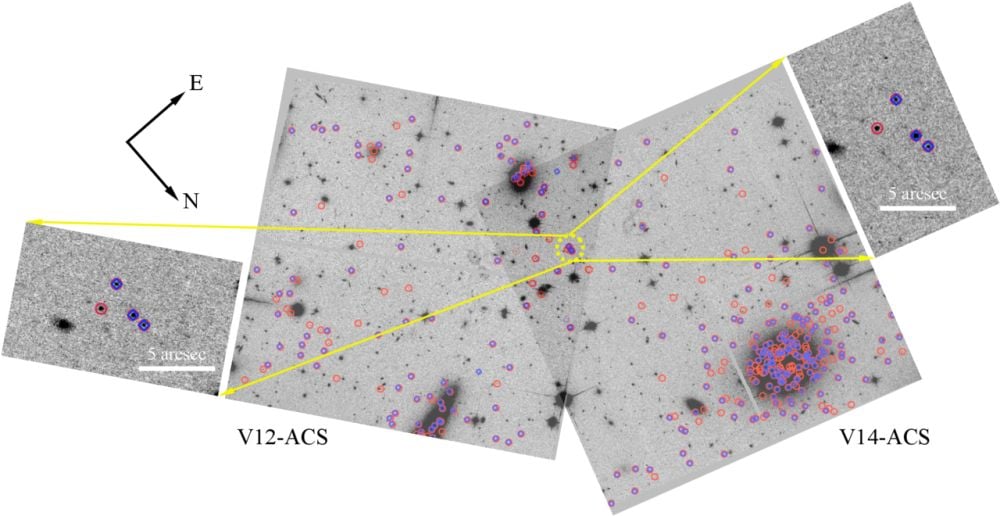

*This figure shows the spatial distributions of GC candidates in the Hubble's F814W images V12-ACS (left) and V14-ACS (right). The Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys captured both images. The red circles and blue diamonds are GC candidates from two different prior surveys. "The GC candidates that constitute CDG-2 from the two images are enlarged and annotated on the side," the authors write. Image Credit: Li et al. 2026. ApJL*

*This figure shows the spatial distributions of GC candidates in the Hubble's F814W images V12-ACS (left) and V14-ACS (right). The Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys captured both images. The red circles and blue diamonds are GC candidates from two different prior surveys. "The GC candidates that constitute CDG-2 from the two images are enlarged and annotated on the side," the authors write. Image Credit: Li et al. 2026. ApJL*

If the assumption that the four GCs are the galaxy's entire population of GCs is correct, then the researchers say that they comprise 16% of its visible content. They also say that CDG-2 is roughly as luminous as six million Sun-like stars. "Our results indicate that CDG-2 is one of the faintest galaxies having associated GCs, while at least ∼16.6% of its light is contained in its GC population," they write in their paper.

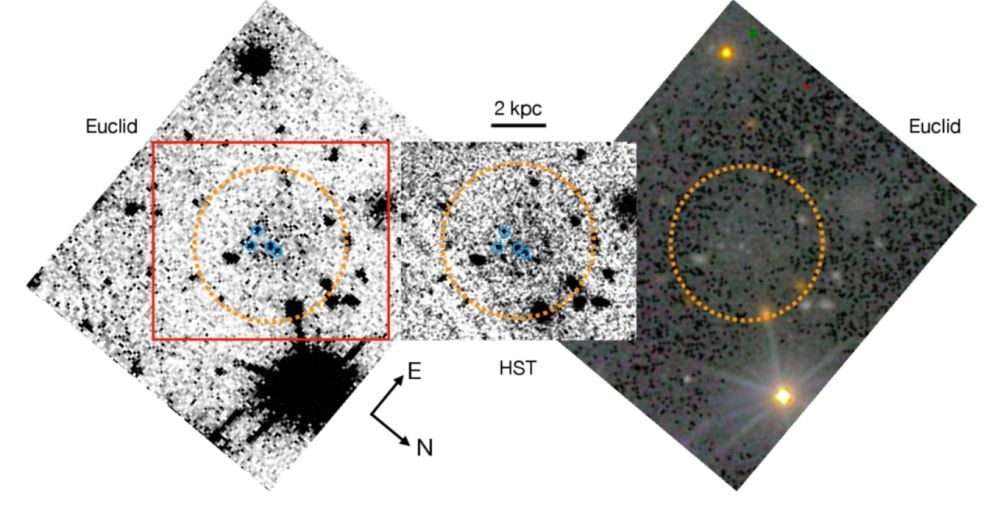

"Given the high statistical significance that CDG-2 is not a random grouping of four GCs, we subsequently stacked the two images of V12-ACS and V14-ACS," they explain. The middle image in the figure below illustrates the result of that action. It shows extremely diffuse emissions around the four GCs, according to the researchers.

*This figure is made up of cutout images from Euclid's VIS and the Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys. The central part stacks both images from the Hubble's ACS and shows extremely diffuse emissions around CDG-2s's four GCs. Euclid data confirms it. Image Credit: Li et al. 2026. ApJL*

*This figure is made up of cutout images from Euclid's VIS and the Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys. The central part stacks both images from the Hubble's ACS and shows extremely diffuse emissions around CDG-2s's four GCs. Euclid data confirms it. Image Credit: Li et al. 2026. ApJL*

"The morphology of the diffuse emission in both the HST and Euclid data is almost identical," the researchers write. They conclude that its presence can't be due to any potential imaging artifacts in either survey.

CDG-2's confirmation immediately brings CDG-1 back into the spotlight. CDG-2's diffuse emissions could provide some constraints on the same from CDG-1. "Even though previous observations did not reveal detectable diffuse emission around CDG-1, the extremity of CDG-2 begs the question as to whether CDG-1 could be an even more extreme “twin” of CDG-2 with hardly any stars formed outside of its GCs or that the GC populations were barely dissolved," the authors write.

"Along the same line of thought, further and higher-quality observations of CDG-1 are imperative since CDG-1 can turn out to be a galaxy that is even more extreme than CDG-2," the authors write. They also say that CDG-1 could be the very first example of a galaxy that is only a dark matter halo without any stars, aside from its GCs.

As for its origins, a likely scenario is that interactions with other galaxies in the Perseus cluster stripped away CDG-2's star-forming gas, leaving behind dark matter. Since GCs are so tightly bound, they can resist tidal forces better. They may be all that remain of the galaxy's initial stellar population.

While the origin of GCs, and their role in galactic evolution, are still unclear, they clearly have astronomical utility. This study shows that GCs could be a reliable indicator of dark galaxies.

Universe Today

Universe Today