Every planet in the Solar System is mysterious in its own way. How did Venus evolve into such a hellscape? Did Mars ever support life? How did life on Earth get started?

Saturn is no exception. With its iconic system of rings and its 274 confirmed moons, Saturn attracts the attention of curious planetary scientists. They want to know how and when the rings formed, and how they're connected to its many moons. Some research shows that the rings are debris from an ancient lunar collision, and some shows they're from moons that drifted too close to Saturn and were torn apart by its overwhelming gravity.

New research to be published in the Planetary Science Journal adds to our current understanding of the Saturnian system. It's titled "Origin of Hyperion and Saturn's Rings in A Two-Stage Saturnian System Instability." The lead author is Matija Ćuk from the SETI Institute. The paper is currently available at arxiv.org.

"The age of the rings and some of the moons of Saturn is an open question, and multiple lines of evidence point to a recent (few hundred Myr ago) cataclysm involving disruption of past moons," the authors write. They explain that Titan, Saturn's largest moon and the second largest moon in the Solar System, drives the evolution of the Saturnian system. It's tidal migration away from Saturn has a powerful effect on the entire system. "The obliquity of Saturn and the orbit of the small moon Hyperion both serve as a record of the past orbital evolution of Titan," they write.

Saturn has an axial tilt of about 26.7 degrees. This is unusual, since scientists expect gas giants to form with much smaller tilts. So, something had to to tilt it, and that something may be Titan's migration away from Saturn.

"Saturn's obliquity was likely generated by a secular spin-orbit resonance with the planets, while Hyperion is caught in a mean-motion resonance with Titan, with both phenomena driven by Titan's orbital expansion," the authors explain.

Previous research proposed that Saturn used to have an additional moon. In this scenario, it had a close encounter with massive Titan, was ejected from its orbit, and was torn apart to form Saturn's rings.

The researchers used simulations to try to understand how this all played out. They wanted to test the idea that an additional moon could get close enough to Saturn to form its rings. They say their findings can explain multiple aspects of the Saturnian system that have puzzled researchers: the young age of Saturn's rings, the strange tilt of Saturn's moon Iapetus, which is inclined by about 15 degrees compared to Saturn's equatorial plane, and Titan's unusual migration rate and lack of impact craters.

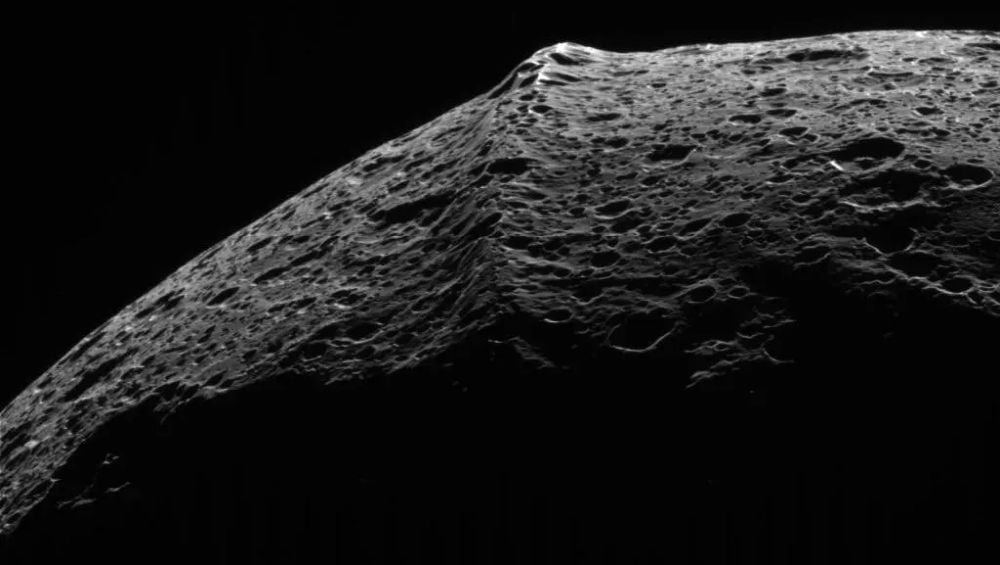

This is where Saturn's moon Hyperion comes in. Hyperion itself is rather strange. It's one of the largest bodies we know of that hasn't been rounded and has an irregular shape. It's sometimes described as being walnut-shaped.

*Iapetus is noted for its unusual equatorial ridge, and the fact that one side of the moon is bright while the other is dark. But its shape is also unusual and has been described as walnut-shaped. Image Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute / Cassini*

*Iapetus is noted for its unusual equatorial ridge, and the fact that one side of the moon is bright while the other is dark. But its shape is also unusual and has been described as walnut-shaped. Image Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute / Cassini*

“Hyperion, the smallest among Saturn’s major moons provided us the most important clue about the history of the system,” lead author Ćuk said in a press release. “In simulations where the extra moon became unstable, Hyperion was often lost and survived only in rare cases. We recognized that the Titan-Hyperion lock is relatively young, only a few hundred million years old. This dates to about the same period when the extra moon disappeared. Perhaps Hyperion did not survive this upheaval but resulted from it. If the extra moon merged with Titan, it would likely produce fragments near Titan’s orbit. That is exactly where Hyperion would have formed.”

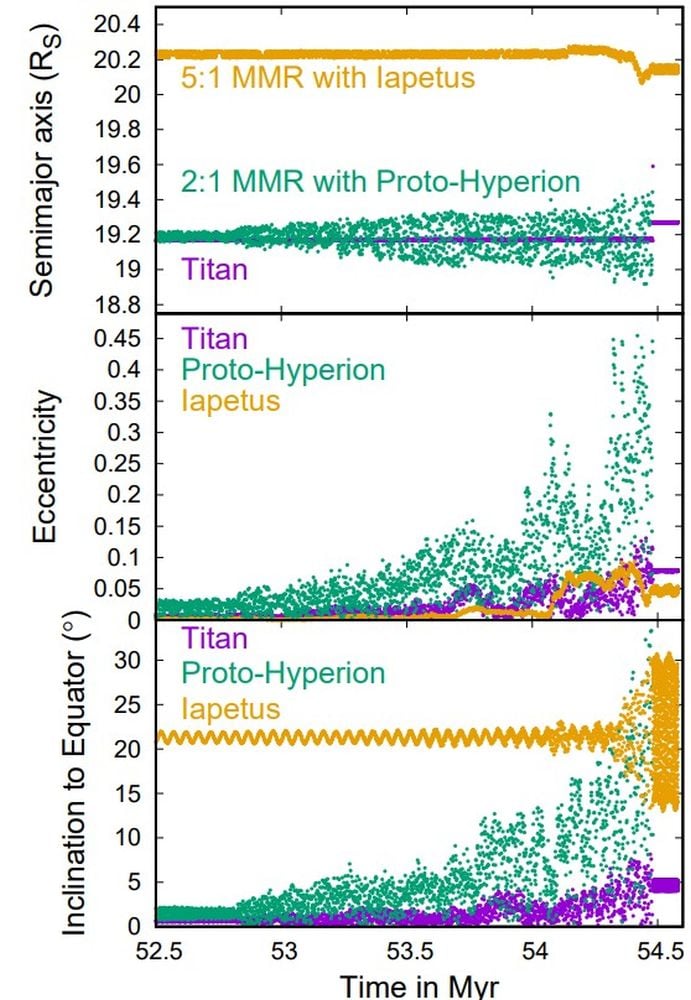

*These panels from the research illustrate some of the simulation results. It shows "one simulation in which proto-Hyperion collided with Titan, and Iapetus’s final orbit resembles the current one," the authors explain. The top panel shows the mean-motion resonance (MMR) between Titan and proto-Hyperion, and between Titan and Iapetus, along with Titan's semi-major axis. " The middle and bottom panels plot the eccentricities and inclinations to Saturn’s equator of the three moons," the authors write. Image Credit: Ćuk et al. 2026. PSJ*

*These panels from the research illustrate some of the simulation results. It shows "one simulation in which proto-Hyperion collided with Titan, and Iapetus’s final orbit resembles the current one," the authors explain. The top panel shows the mean-motion resonance (MMR) between Titan and proto-Hyperion, and between Titan and Iapetus, along with Titan's semi-major axis. " The middle and bottom panels plot the eccentricities and inclinations to Saturn’s equator of the three moons," the authors write. Image Credit: Ćuk et al. 2026. PSJ*

When Saturn's spin-orbit resonance with the other planets was broken, Hyperion was also formed, according to the simulation results. The researchers propose that the additional moon was an outer, mid-sized satellite that they're calling "proto-Hyperion." The breaking of Saturn's spin-orbit resonance destabilized proto-Hyperion, and it collided with proto-Titan. This happened about 400 million years ago.

Some of the debris from the collision accreted onto Hyperion, which can help explain its shape. Proto-Hyperion's perturbation prior to the collision can also explain Iapetus' orbital inclination. It also excited Titan's orbital eccentricity. This set off a chain of events where Titan's resonant interaction with the inner moons “Proto-Dione” and “Proto-Rhea” created destabilization, collisions, and the eventual re-accretion of Saturn's inner moons and its rings. Most of the debris accreted into moons, while a smaller amount formed the rings.

The merger of proto-Titan and proto-Hyperion also explains Titan's lack of impact craters. Though the large moon is ancient, its surface is simply too young have suffered many impacts.

*We don't have great images of Titan's surface, but the ESA's Huygens probe captured some images during its descent. This composite image is made from images taken from about 8 km above the surface. Each pixel is about 20 meters. No impact craters are visible. Image Credit: NASA/ESA*

*We don't have great images of Titan's surface, but the ESA's Huygens probe captured some images during its descent. This composite image is made from images taken from about 8 km above the surface. Each pixel is about 20 meters. No impact craters are visible. Image Credit: NASA/ESA*

Almost anybody who looks at images of the Saturnian system can tell it's a dynamic environment. The researchers have presented a clear timeline for the Saturnian system's history that can explain what we see in the system now.

"While the events described here took place hundreds of millions of years ago and are difficult to confirm directly, recent observations have consistently challenged previous models and revealed new dynamical pathways," the authors write. "Our hypothesis predicts a dynamically active and relatively young Saturnian system whose present configuration is the product of recent, dramatic events."

Only deeper research, hopefully involving eventual missions to Saturn's moons, can confirm this hypothesis. The age of Titan's surface, and of other moons, is a critical part of this. Fortunately, NASA's Dragonfly mission to Titan will send a rotorcraft to the moon's surface. It's scheduled for launch in July 2028, and will reach Titan in 2034. Data should start flowing back to Earth shortly thereafter, and will answer some of our questions.

"Whether or not our specific sequence of events is confirmed, we think this work helps frame new hypotheses about the evolution of Saturn’s satellite system," the authors conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today