It’s an age-old debate in space circles: Should humanity’s first city on another world be built on the moon, or on Mars?

As recently as last year, SpaceX founder Elon Musk saw missions to the moon as a “distraction.” In a post to his X social-media platform, he declared that “we’re going straight to Mars.”

But last week, Musk said he’s changed his mind: “For those unaware, SpaceX has already shifted focus to building a self-growing city on the Moon, as we can potentially achieve that in less than 10 years, whereas Mars would take 20+ years,” he wrote on X.

How realistic is either option, particularly on a 10- to 20-year time frame? In a new book titled “Becoming Martian,” Rice University evolutionary biologist Scott Solomon lays out the possibilities as well as the perils that could make Musk’s job more challenging than he thinks.

“The more research I did on this topic, and the more labs I visited, and papers I read, and experts I spoke with, what became clear to me is that we have some pretty big gaps in our knowledge, in our understanding of what the reality would be like,” Solomon says in the latest episode of the Fiction Science podcast.

Click to launch the Fiction Science podcast on Spotify

To be sure, humans have been flying in space for 65 years, and a library’s worth of research has been done into the health effects of spaceflight. But there’s been precious little opportunity to study what long-term exposure to the space environment does to the human body. One of the most ambitious projects focused on how 340 days on the International Space Station in 2015-16 affected NASA astronaut Scott Kelly, who wrote the foreword for “Becoming Martian.”

“Long-term spaceflight takes a toll, physically and psychologically,” Kelly acknowledges in his foreword. One of the biggest concerns has to do with space radiation. Kelly’s level of exposure caused minor mutations in his chromosomes, but settlers living on the surface of the moon or Mars would face more serious exposure levels.

Extraterrestrial city planners could address the radiation problem by putting their populations in habitats that are shielded by a thick layer of soil or built within a lava tube. Solomon notes that, in ancient times, thousands of people inhabited an underground city near the modern Turkish town of Derinkuyu. But those residents were able to emerge from their holes and roam around the surface — an option that would be potentially dangerous for settlers on the moon or Mars.

“I don’t really want to go to Mars if I’ve got to be underground all the time,” Solomon says. “That would be a real bummer if you make it all the way to Mars and you don’t get to go explore on the surface.”

Could space settlers modify the Martian environment to make it more Earthlike? In the book, Solomon lays out the possibilities for terraforming Mars and comes to the conclusion that it “would be an uphill battle, one that would require continual maintenance.”

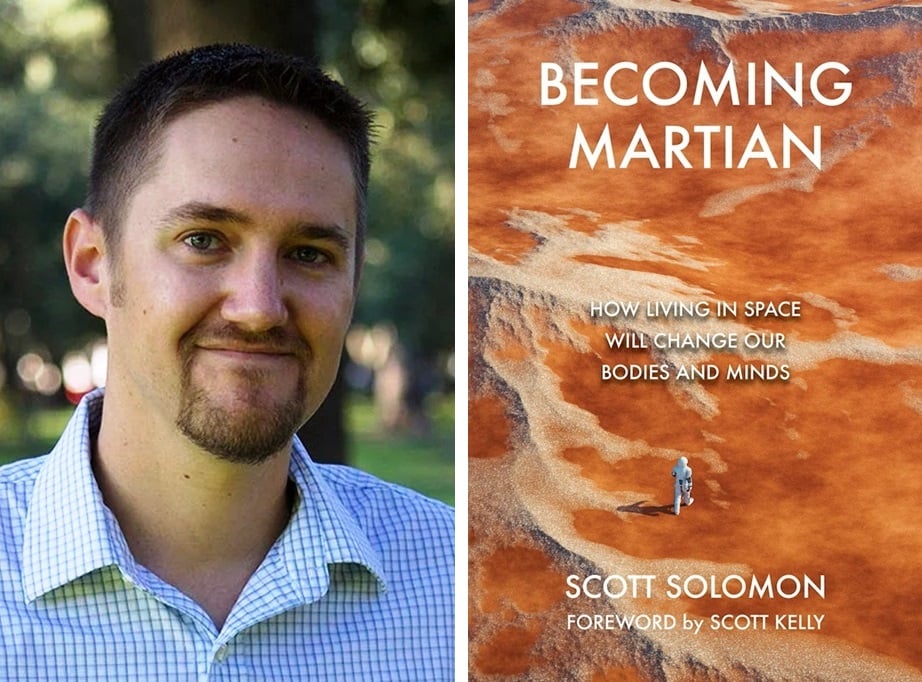

Scott Solomon, the author of "Becoming Martian," is a biologist, professor and science communicator at Rice University. (Photo via Rice University; book cover via the MIT Press)

Scott Solomon, the author of "Becoming Martian," is a biologist, professor and science communicator at Rice University. (Photo via Rice University; book cover via the MIT Press)

Providing food and water for extraterrestrial city dwellers would be another big challenge. Even though the surfaces of the moon and Mars are both bone-dry and bone-chillingly cold, both those environments appear to have enough reserves of water ice to sustain settlements. But settlers would probably have to grow their own crops instead of depending on shipments from Earth. And they’d probably have to forget about bringing livestock.

“I do suggest that we might consider not bringing animals with us, and specifically mammals and birds,” Solomon says. He gives two reasons: First of all, those animals would be competing with the settlers for scarce resources. “Maybe the most practical way to create your settlement on Mars is for everyone to be vegan,” he says.

Animals could also pose a public health threat. “The majority of the infectious disease that we deal with … come from infections that were once infecting animals, and then they switched hosts, and they start infecting humans,” Solomon says. “If we left Earth and chose to not bring any birds and mammals with us, we could actually minimize the chances of having new infectious disease emerge.”

Humans won’t be the only creatures living in extraterrestrial cities. Each settler will be carrying trillions of gut microbes that play an essential role in human health. Gut microbiomes might even be genetically engineered for optimal performance in the space environment. “We know that those microbes evolve in just the same ways that any of us will evolve when we leave Earth,” Solomon says.

How humans might evolve

In the book, Solomon delves deeply into how living in space will change the human species. For example, extraterrestrial city dwellers could evolve to become more tolerant of space radiation. Some researchers are even talking about using genetic engineering to give humans a greater capacity to resist radiation damage to DNA.

“They’ve already had success with, for example, taking genes from tardigrades, which are famously very hardy and are even able to tolerate some of the conditions of space,” Solomon says. “They’re able to take some of the genes that help tardigrades to do that and implant them into human cells growing in culture .. and those human cells will actually express the proteins that are the same proteins that tardigrades are using to help them with radiation damage suppression.”

Another concern has to do with bone density. Over the years, studies have shown that astronauts tend to lose bone mass in microgravity, and it’s possible that people who get used to the reduced-gravity environment on the moon or Mars will have thinner, weaker bones than their earthly ancestors.

That could be a big problem for an extraterrestrial city’s second generation. “By the time a woman reaches the age at which she’s having children, her bones would be substantially weaker than they would have been on Earth,” Solomon says. “And that’s where I think childbirth becomes a much riskier prospect.”

Solomon thinks the safest way to give birth on Mars will be by caesarean section — which would have implications for future generations in those alien cities. “It means that the head is no longer constrained to have to fit through the birth canal,” he says. “That has been a constraint that has existed throughout all of human evolution, and even before. So, if the head is no longer constrained, then the head can get larger. You might actually imagine a scenario in which Martians have larger heads. … Then it does start to look a little bit more like science-fiction depictions of aliens.”

People who grow up in the reduced gravity of the moon or Mars might find it difficult if not impossible to spend an extended period of time back on Earth. The microbiome issue might also contribute to a sundering of the human species, Solomon says.

“If you come back to Earth, Earth’s microbes are going to be dangerous to you,” he says. “I think that’s actually a potential challenge of having an interplanetary future. If we want to have people living on different planets, they might not be able to easily move back and forth between those planets because of the risk of disease.”

Why do it?

Considering all the challenges, is building a city on the moon or Mars worth the risk? Solomon says the risks aren’t as high for lunar settlement as they are for Martian settlement, largely because it would be easier to make frequent trips between Earth and the moon. That’s one of the reasons why, at least for now, the moon trumps Mars.

The potential for Earth-moon commerce is a big factor behind the interest in lunar settlement. Commercial ventures including Seattle-based Interlune are already looking into ways to extract helium-3 and other resources from lunar soil and send them back to Earth. And Musk came up with another business idea: building a mass driver on the moon to catapult satellites into space.

“I can’t imagine anything more epic than a mass driver on the moon, and a self-sustaining city on the moon, and then going beyond the moon to Mars, going throughout our solar system and ultimately being out there among the stars,” Musk said at an xAI all-hands meeting.

Elon Musk talks about his vision for industrializing the moon, in front of a representation of a lunar mass driver. (xAI via X)

Elon Musk talks about his vision for industrializing the moon, in front of a representation of a lunar mass driver. (xAI via X)

Anyone who’s read Robert Heinlein’s classic science-fiction novel, “The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress,” knows that a lunar mass driver can also be used as a deadly weapon. That brings up another motivation for missions to the moon: geopolitics.

NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman referred to the U.S.-China moon race last year during his second Senate confirmation hearing. “This is not the time for delay, but for action, because if we fall behind, if we make a mistake, we may never catch up, and the consequences could shift the balance of power here on Earth,” Isaacman said.

Solomon notes that the connection between geopolitics and the space program goes back decades, to the U.S.-Soviet moon race of the 1960s. “I guess what I’d say is, I want to make sure that if we are moving forward quickly, regardless of the motivations, we’re still keeping human well-being first and foremost — and we’re not putting people in harm’s way just to try to get there first,” he says.

So, what’ll it be? A city on the moon? A city on Mars? Or none of the above? Solomon thinks it’s possible to “have boots on the ground” on the moon within a few years, and on Mars within a decade. But that’s different from building a self-sustaining city.

“I hope that we’re not too close to a true city on the moon or on Mars, because I worry about what would happen to the kids that would need to live in that city,” Solomon says. “If adults are willing to take the risks of going and working there, and spending as much time as they want there, that’s fine. … But I have pretty serious concerns about the idea of bringing a child into that environment, especially if it’s possible that that child wouldn’t be able to ever come to Earth — which I think is possibly the case.”

For more from Scott Solomon, check out his previously published book, “Future Humans: Inside the Science of Our Continuing Evolution”; and his podcast, “Wild World With Scott Solomon.”

My co-host for the Fiction Science podcast is Dominica Phetteplace, an award-winning writer who is a graduate of the Clarion West Writers Workshop and lives in San Francisco. To learn more about Phetteplace, visit her website, DominicaPhetteplace.com.

Check out the original version of this report on Cosmic Log for bonus reading recommendations from Solomon, and for links to previous Fiction Science podcasts that focus on space settlement. Stay tuned for future episodes of the Fiction Science podcast via Apple, Spotify, Player.fm, Pocket Casts and Podchaser. Fiction Science is included in FeedSpot's 100 Best Sci-Fi Podcasts. If you like Fiction Science, please rate the podcast and subscribe to get alerts for future episodes.

Universe Today

Universe Today