[/caption]

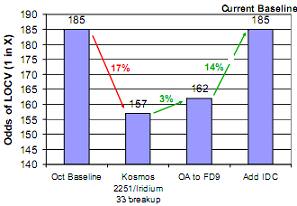

There’s good news and bad news for the upcoming Hubble repair mission. The good news is that the statistical threat posed to space shuttle Atlantis and her crew by micro-meteoroid orbiting debris (MMOD) is currently no greater than last year, even with the collision of two satellites in February and other recent satellite breakups. The chance of the shuttle being hit by MMOD during a mission to Hubble is 1 in 185. But that’s also the bad news. The 1 in 185 chance of a catastrophic impact to a shuttle in Hubble’s orbit is, obviously, quite high, and higher than NASA’s limit of 1 in 200. The final decision of whether this risk is acceptable will be discussed at a Flight Readiness Review meeting on April 30. It is anticipated that NASA will override the limit and accept the risk. Without a servicing mission by a space shuttle crew, the telescope is not expected to last more than another year or two.

According to an article on NASASpaceflight.com, NASA analysts were able to reach this particular ratio by making use of the known probability of detecting and repairing critical Thermal Protection System damage while on orbit, factoring in the length of the mission and orientation of the shuttle during the mission (both attached and unattached to the Hubble) and even adding in how a “rescue mission” would come into play in the event of a catastrophic impact.

NASA guidelines say the Space Shuttle Program cannot accept a Loss of Crew and Vehicle (LOCV) ratio in excess of 1 in 200.

Immediately after the Kosmos/Iridium satellite collision and factoring in other recent breakups which include the Chinese ASAT/Fengyun 1C, the Kosmos 2421, the risk of LOCV increased to 1 in 157 for Atlantis.

But with the long delay for STS-125, mission planners were able to investigate and implement several mitigation tactics and changes to the flight’s activities that brought the risk back down to 1 in 185 chance.

The NASA team is also looking at different options that will reduce the risk, which include eliminating one EVA day (which would reduce risk by ~6 percent to 1 in 196), eliminating two EVA days (which would reduce risk by ~12 percent to 1 in 208), or eliminating the crew off duty day after the Hubble is released (which would reduce risk to 1 in 201).

Delaying the mission would likely have no effect on the statistical risk. The mission was already delayed when data handling processor on the spacecraft failed in September 2008 and again due to Hurricane Ike in October 2008. With the mitigation tactics, the 1 in 185 chance is no higher than it was determined to be last September.

NASA also analyzed the risk for STS-400 rescue flight, which is 1 in 294. That ratio is only if the crew does an inspection of the Wing Leading Edge panels and Nose Cap and has a short mission duration of just seven days. If the STS-400 crew does not perform any TPS inspection, the LOCV ratio rises to 1 in 217.

But everything is going full-steam-ahead for the mission; Atlantis is on launch pad 39 B being prepared for the mission, Endeavour will be sent to pad 39 A tomorrow (Friday) to prepare for the STS-400 rescue mission, if needed (otherwise Endeavour will move to pad 39 B for the next shuttle mission, STS-127 to the ISS scheduled for June) and the the STS-125 crew is in full training and preparations for the flight.

Credit: NASASpaceflight.com

Fingers crossed, let’s hope launch date won’t slip, again!

Go, Atlantis, go!

I wonder what the accident risk was for the Apollo missions. I’ve seen movies and read articles and was horrified… and that was before the days of space junk. Nobody really seems to have cared – the missions were part of a Cold War battle, the astronauts were soldiers….

Thanks be to Goodness we’ve come a long way since then.

And there’s got to be a way of dealing with the junk!!! Right now, it almost looks to me like the era of manned space flight might gradually be approaching a premature end.

Let’s just get that great telescope fixed! The astronauts, like Hubble + his namesake telescope will be heroes!

I found this paragraph from the NASASpaceflight web page interesting:

“Recent satellite breakup events have increased the background Orbital Debris flux by 36 percent.”

These breakups include the Chinese ASAT/Fengyun 1C, the Kosmos 2421, and the Kosmos 2251/Iridium 33 satellite collision – all of which respectively account for 27 percent, 1 percent, and 71 percent of the total orbital debris flux increase.

The Kosmos/Iridium collision generated over twice as much orbital debris as the Chinese ASAT test did!

@ NoAstronomer

Probably, because there were two satallites involved!?

such a strange, growing problem with all that stuff up there.

reminds me of that billy bragg lyric: “i saw 2 shooting stars last night / i wished on them, but they were only satellites”

Look – the 1 in 200 risk is a completely arbitrary number. God only knows how they came up with it, but in the end it can’t have been based on anything other than a whim.

Eliminating EVAs or other crucial aspects of the mission just to bring the number back from one small arbitrary number to another slightly smaller arbitrary number is ludicrous – ‘Wow! We scrapped half of our EVA time and the mission results will suffer greatly for that, but we’ve reduced our mission risk by 3.26954% according to my imprecise calculations!!’.

Talk about false economy – if they’re seriously considering scrapping two EVA days to reduce the risk by a minimal amount, well then, why don’t they just scrap a couple of more EVA days to reduce the risk to 1 in 218? Get the whole thing done at once! Of course, that may place undue stress on the astronauts and be even less safe, but that kind of thing isn’t tangible or calculable and 1 in 218 does, on the face of it, seem like a far more acceptable mission risk because 218 is a number OVER 200, unlike 185. Just like 1 in 201 would be acceptable for everyone involved, but 1 in 199 would obviously be far too dangerous.

Hell – let’s just kill the whole thing – that’ll be much safer!

Astronauts are big boys – they know the risks (apparently NASA can work it out precisely for them!). NASA management needs to grow a pair and get on with it.

@Astrofiend :-

“Astronauts are big boys – they know the risks”

Apparently not this one, since NASA guidelines previously stated that they would not be subjected to a risk of death estimated to be greater than 1 in 200.

I wouldn’t cancel the mission, but I’d offer each astronaut the opportunity (unlikely to be taken) to withdraw at no penalty to their careers or pay. If your guidelines say no more than 1 in 200 calculated risk, then you shouldn’t waive that threshold on behalf of other parties, no matter how “arbitrary” it might be. That’s inequitable.

A while back there was an “art” exhibite that was composed of a chair to sit in with a loaded rifle pointed at it.

The rifle had a random trigger on it where rhe rifle could go off at any time.

People could sit in the chair knowing that there was a chance that the gun could go off.

I wonder how many would sit in it knowing there was a 1 in 200 chance of ending up dead ?

The chair offered nothng other than the “thrill”

of sitting in it.

The shuttle missions are what they are stated to be “Missions”.

Not making a statement here, just an observation.

A while back there was an “art” exhibite that was composed of a chair to sit in with a loaded rifle pointed at it.

The rifle had a random trigger on it where rhe rifle could go off at any time.

People could sit in the chair knowing that there was a chance that the gun could go off.

I wonder how many would sit in it knowing there was a 1 in 200 chance of ending up dead ?

The chair offered nothng other than the “thrill”

of sitting in it.

The shuttle missions are what they are stated to be “Missions”.

Not making a statement here, just an observation.

I’ve been looking for an appropriate article to ask this question; this seems to be a good one for it.

(Yes, I keep tin foil handy at all times, LOL)

I’ve logged 3200 skydives, about 1/2 of them as an instructor or videographer (of student jumps). “Big sky, little guy” has worked VERY well for the entire history of the sport. Every skydiver-aircraft collision I’m aware of (in HISTORY) involved either super-tight airspace (an airshow; 1 of those IIRC), or multiple jumpships flying in formation for a large formation skydive, and a jumper exited one craft in the (malformed, obviously) formation, and hit another craft in the formation – and less than a handful of those, in the entire history of the sport. Although it’s illegal in the US (not so in all countries), I’ve “busted” at LEAST 100 clouds in my career w/o ever hitting a random plane (this wasn’t done recklessly; we were in a remote location off normal flight lanes). And no, there’s no way to describe that experience – the most surreal world I’ve ever been in, if only for less than a minute – MAX – at a time.

“Big sky, little guy” has a long-term, proven track record in the sport – on a MUCH smaller and more crowded playing field.

I’ve had a (c-)theory since the Kosmos 2251/Iridium collision – it was my first thought upon hearing the details:

Kosmos 2251 was known to be a dead bird – just like the Chinese Fengyun 1C was. It was non-operational but likely had some fuel left. Has anyone addressed the possibility that 2251 was STEERED into a collision path with the Iridium bird? Effectively the same mission as the Fengyun 1C shootdown, but simply a differing technique? Wouldn’t NASA be able to tell if this had occurred purposely? They track all the orbits; wouldn’t such a maneuver be detectable?

It’s hard typing long posts wearing all this tin foil. 😉