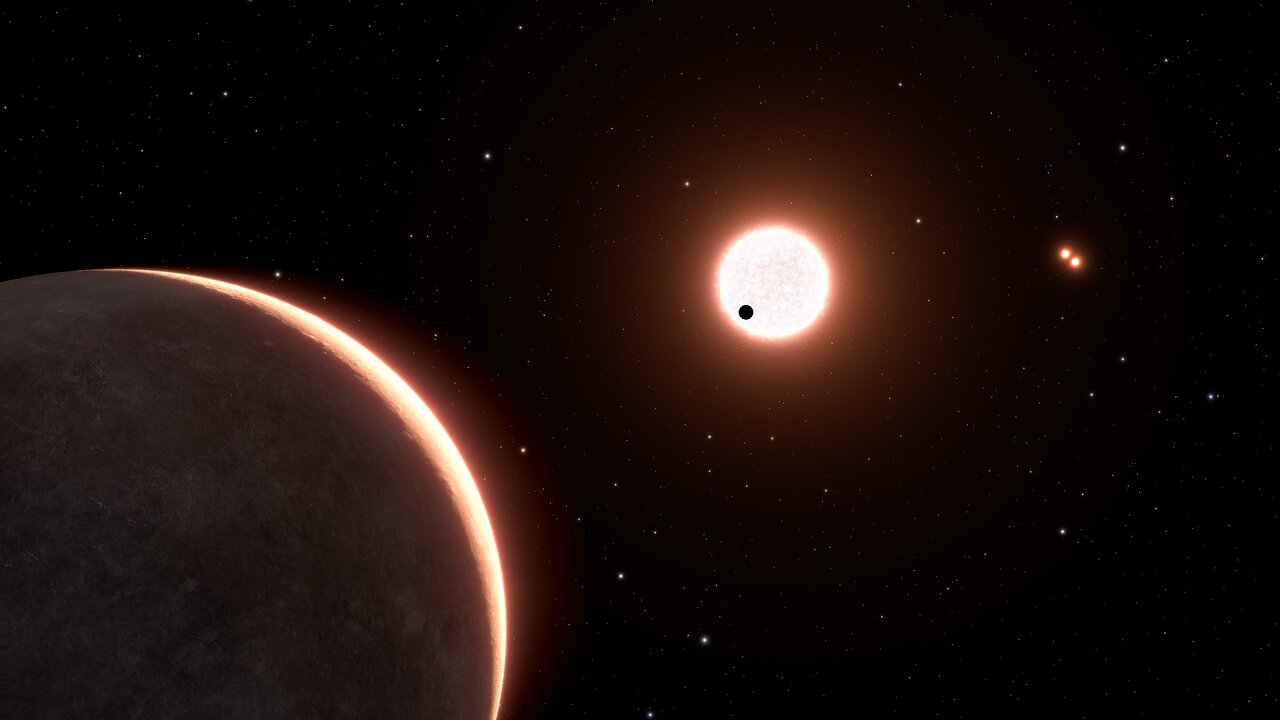

Twenty-two light-years away, a rocky world orbits a red dwarf. It’s called LTT 1445Ac, and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) found it in 2022. However, TESS was unable to gauge the small planet’s size.

That’s okay. The venerable Hubble took care of it.

TESS detects planets with the transit method. When an exoplanet transits in front of its star, it creates a measurable dip in light that TESS detects. But things have to line up right. The planet has to transit between TESS and the star. When that happens, TESS can not only detect the planet but also measure its size to some degree.

But LTT 1334Ac is kind of in no-man’s-land from our perspective. The geometry is right for detection, but it’s misaligned just enough that the planet may have performed a ‘grazing transit.’ That’s when the planet transits in front of a portion of the star but not all of the star. That means that size measurements give an inaccurate lower limit for the planet’s diameter. Unfortunately, TESS doesn’t have the resolution to tell us whether LTT 1334Ac was performing a grazing transit or not.

But the workhorse Hubble Space Telescope does.

“There was a chance that this system has an unlucky geometry, and if that’s the case, we wouldn’t measure the right size. But with Hubble’s capabilities, we nailed its diameter,” said Emily Pass of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“Our measurement is important because it tells us that this is likely a very nearby terrestrial planet.”

Emily Pass, Harvard-Smithsonian CfA

Pass is the lead author of a new paper in The Astronomical Journal titled “HST/WFC3 Light Curve Supports a Terrestrial Composition for the Closest Exoplanet to Transit an M Dwarf.”

“Previous studies of the exoplanet LTT 1445Ac concluded that the light curve from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) was consistent with both grazing and nongrazing geometries. As a result, the radius and hence density of the planet remained unknown,” the paper states. But not anymore.

Hubble determined that LTT 1334Ac does make a full transit across its star rather than a grazing transit. That means that the planet’s actual diameter is 1.07 times Earth’s diameter. It also confirms that the planet is rocky and has about the same surface gravity as Earth.

Grazing transits are an obstacle in exoplanet science. TESS is a powerful planet-finder, but it can’t do everything. It can’t always determine if an exoplanet is performing a grazing transit or a full transit. Astronomers are developing models of them to try to understand how to detect them better and how abundant grazing transits are.

In a 2022 paper, researchers wrote that even though they’re rare due to geometric selection effects, “Grazing transits present a special problem for statistical studies of exoplanets.” They also explained that “A failure to accurately model grazing transits can, therefore, lead to biased inferences even for cases where the planet is not actually on a grazing trajectory.”

There’s no full solution to grazing transits yet. But at least the Hubble can help in some cases. And though its observations determined the planet’s size and its rocky makeup, habitability is out of the question. LTT 1334Ac’s surface temperature is about 260 Celsius (500 F.) Water would boil away at that temperature, and life would have no chance.

There are two other planets in the system, both larger than LTT 1334Ac. There are also two more stars in the system, and all of them are red dwarfs. There’s a lot going on in this system, but observations show that the entire system is likely co-planar. And the fact that LTT 1334Ac performs full transits means it’s a great candidate for more study.

“As the nearest terrestrial exoplanet to transit an M dwarf (alongside LTT 1445 Ab), this planet is an exciting target for atmospheric characterization, particularly now that it is known to be nongrazing and its radius is therefore appropriately constrained,” the paper states.

“Transiting planets are exciting since we can characterize their atmospheres with spectroscopy, not only with Hubble but also with the James Webb Space Telescope,” Pass said in a press release. “Our measurement is important because it tells us that this is likely a very nearby terrestrial planet. We are looking forward to follow-on observations that will allow us to better understand the diversity of planets around other stars,” said Pass.

This research highlights the synergy between different telescopes and how that synergy can lead to deeper understandings. It also shows that the Hubble is still a powerful science instrument.

“Hubble remains a key player in our characterization of exoplanets,” said Professor Laura Kreidberg of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, who was not part of this study. “There are precious few terrestrial planets that are close enough for us to learn about their atmospheres — at just 22 light years away, LTT 1445Ac is right next door in galactic terms, so it’s one of the best planets in the sky to follow up and learn about its atmospheric properties.”

The paper’s authors agree. “As the nearest terrestrial exoplanet to transit an M dwarf (alongside LTT 1445 Ab), this planet is an exciting target for atmospheric characterization, particularly now that it is known to be nongrazing and its radius is therefore appropriately constrained,” they conclude.