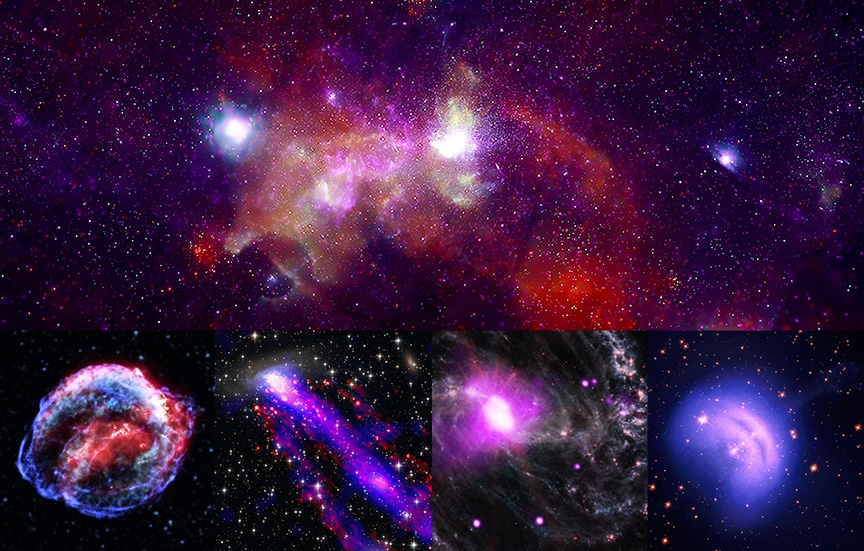

One of the miracles of modern astronomy is the ability to ‘see’ wavelengths of light that human eyes can’t. Last week, astronomers put that superpower to good use and released five new images showcasing the universe in every wavelength from X-ray to infrared.

Combining data from both Earth- and ground-based telescopes, the five images reveal a diverse set of astronomical phenomena, including the galactic centre, the death throes of stars, and distant galaxies traversing the cosmos.

Vela Pulsar

The Vela Pulsar used to be a massive star, until it exploded ~11,000 years ago. This image features the remains of that explosion. Debris, lit up by high energy X-rays, was captured by both the Chandra X-Ray Observatory and the Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE), and is represented in this image in blue and purple. The background starfield was captured in optical light by the Hubble Space Telescope.

When Vela exploded, the core of the dead star collapsed to form a quickly spinning neutron star, which is hidden within the debris field today. It rotates 11.195 times every second, sending out pulses of energy at radio frequencies with highly predictable regularity. The Vela Pulsar is continuously shepherding the surrounding nebula with powerful winds, shaping the wavelike features in the photo, and surrounding a jet of particles and energy that shoots off to the upper right.

The Vela Pulsar is within our own galaxy, just 1000 light years away, and is one of the brightest radio pulsars in the night sky.

Kepler’s Supernova Remnant

Twenty times further away than the Vela Pulsar – but still within our own galaxy – is Kepler’s Supernova Remnant, another exploded star. In this instance, a white dwarf in a binary system feasted on its companion star until reaching an unsustainable mass, causing it to go supernova. The explosion occurred in 1604 and was visible to the naked eye during the daytime for three weeks. Famed 17th-century astronomer Johannes Kepler spent over a year studying the supernova remnant, and the object was later given his name.

The blue in this image (Chandra) shows a blast wave from the explosion, while red marks debris seen in infrared by the Spitzer Space Telescope, and in optical by Hubble (yellow).

Galactic Centre

26,000 light-years away lies the very heart of the Milky Way Galaxy. This is a dense, energetic region of space, crowded with stars and superheated gas. Hiding in the centre of it all is a supermassive black hole called Sagittarius A. The orange, green, blue, and purple colors in the image each represent a different frequency of X-rays captured by the Chandra X-Ray Observatory.

NGC 1365

60 million light-years away – well beyond the Milky Way – is NGC 1365, a spiral galaxy not too dissimilar from our own. At its core hides a supermassive black hole surrounded by hot gas, lit up in X-ray light captured by Chandra (pink and purple). The red, green, and blue colors in this image represent the galaxy as seen in infrared light by the James Webb Space Telescope.

NGC 1365 features a prominent ‘bar’ across the centre of the galaxy, a dense area stretching from the galactic core out to the spiral arms. Barred galaxies are common (the Milky Way is one – probably), and bars play an important role in galactic evolution, funnelling gas and dust from the galaxy’s outer regions down into the galactic centre.

ESO 137-001

213 million light-years away lies ESO 137-001, another spiral galaxy seen in white (optical light from Hubble) in the upper left. This galaxy is moving at 1.5 million miles per hour through the universe, heading towards the centre of a galactic cluster called Abell 3627.

Abell 3267 is full of superheated interstellar gas and dust, and as the galaxy pushes through it, it is being stripped of its own gas through a process called ram pressure stripping. This image highlights the twin tails of gas being left behind. The red hydrogen atoms (seen by ESO’s Very Large Telescope) and energetic blue gas clouds (seen in X-ray by Chandra) form twin tails, stretching more than 260,000 light years behind the fast-moving galaxy.

Learn More:

You can peruse the full gallery of images here. You’ll also find the individual layers of each image, showing the different wavelengths of light on their own before they were composited together.