In our search for life on other worlds, the one we’ve most explored is Mars. But while Mars has the makings for possible life, it isn’t the best candidate in our solar system. Much better are the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, which we know have liquid water. And of those, perhaps the best candidate is Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Based on observations both from Earth and from the Cassini mission, Enceladus seems almost perfect for life as we know it. The moon has been observed venting plumes of water ice, indicating it has liquid water beneath its surface. The plumes contain silicate grains, which strongly imply the presence of subsurface thermal vents, and they also contain complex organic molecules. For these reasons, the latest Planetary Science Decadal Survey has recommended a mission to Enceladus. Naturally, there are several mission proposals, but one of them is Astrobiology eXploration at Enceladus (AXE).

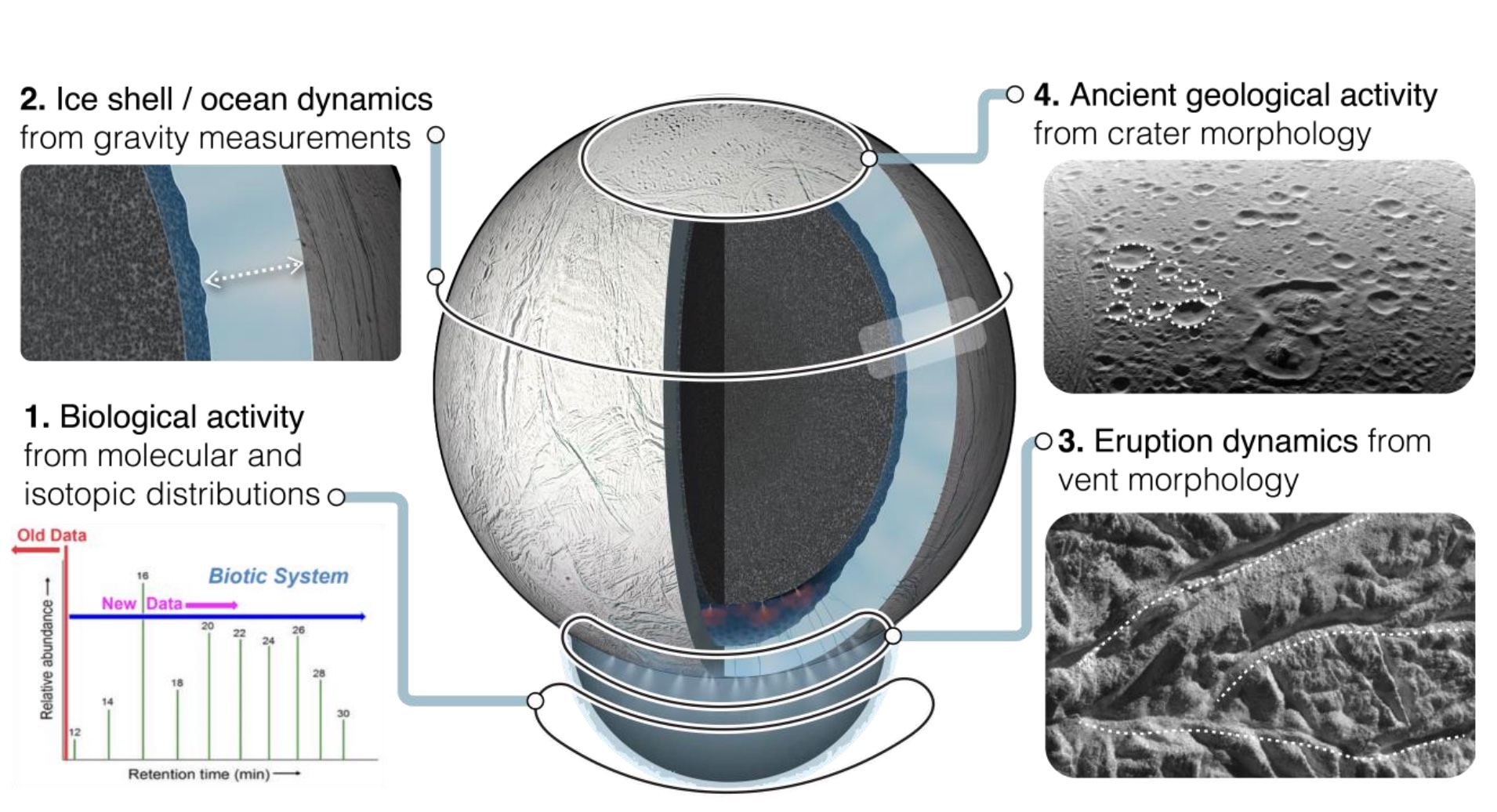

The AXE mission was developed as part of the Planetary Science Summer School program at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It is a proposed orbital mission and it would have four key science objectives.

The first of these would be to look for biological signatures, specifically chemicals such as amino acids and fatty acids. This would be done by flying the probe directly through plumes to capture and analyze their chemical and physical composition.

The second would look at whether Enceladus is in thermal equilibrium. While we know the moon has liquid water, we don’t know whether this is due to a transient warming of the world, or whether it is due to a long-term cycle of heat generation and radiation. Liquid water would need to be present on a scale of a billion years or more for life to have formed on Enceladus. This would be done by looking at both the thickness of surface ice on the moon as well as studying how its orbit has changed since the Cassini mission.

The third objective would look at how water plumes form on the moon. One mechanism could be that large open fissures expose liquid water causing it to boil off to the vacuum of space. Another way would be through cryovolcanism, where heated water bursts through the moon’s surface, similar to the way volcanoes erupt on Earth. This can be studied by making high-resolution images of the vents.

The last objective would look at how geologically active Enceladus is. If there is thermal activity below its crust that drives geologic activity on its surface, then this should be evidenced in the cratering pattern of the moon.

All of this would tell astronomers whether the necessary conditions for life have long existed on Enceladus, and possibly even reveal the presence of extraterrestrial life. But AXE would be an ambitious mission. It would take 9 years for the mission to reach Saturn and another year for it to bring the probe into a close orbit of Enceladus. It would then need to make at least 30 flybys of the moon to gather enough gravitational and imaging data for the mission, as well as at least 5 close flybys to capture material from the plumes.

The AXE mission isn’t the only proposed mission to Enceladus. There are others, including the Orbilander mission that would land a probe on the moon. But whatever mission is approved in the long run, it’s clear that Enceladus is worth visiting.

Reference: Seaton, K. Marshall, et al. “Astrobiology eXploration at Enceladus (AXE): A New Frontiers Mission Concept Study.” The Planetary Science Journal 4.6 (2023): 116.

It is easy to agree with the title, Enceladus is the next astrobiology target after the closer Mars (and Venus) gets their due.

“Liquid water would need to be present on a scale of a billion years or more for life to have formed on Enceladus.”

Not necessarily. Phylogenetic evidence implies life evolved in the deep ocean – in Enceladus analog conditions, by the way – and early. Admittedly the methods are biased towards pushing the root early, but there is no evidence against that. Some take the lack of fossil before 3.8 – 3.5 billion years as indicative, but there are reasons to believe continental crust and so fossil bearing sediments didn’t appear before then [“Did Life Need Plate Tectonics to Emerge?”, Evan Gough, Universe Today 2023].

“Tarduno and his fellow researchers were examining zircons from South Africa’s Barberton Greenstone Belt, the home of some of Earth’s oldest exposed rock. They found that the zircons they studied from between 3.9 billion and 3.4 billion years ago show no change in magnetic properties. The conclusion is that during that time period, latitudes didn’t change either, meaning the continents didn’t move due to plate tectonics.”

The recent discovery of the possibility of Venus having a squishy lid regime with volcanism building rocks and what looks like a volcanic granite dome inside Moon seems to tie together Venus, Earth and Moon crust formation regimes. But even if not it shows that the billion year of seeming hiatus is an upper and not lower limit for evolving life. All the more reason to go to Enceladus and have a look.