The commercial spaceflight revolution didn’t begin with Elon Musk. Or with Jeff Bezos, or Richard Branson, or any of the other billionaires who’ve spent a fortune on the final frontier over the past 20 years.

Would you believe it began with Jules Verne in the 1860s?

That’s the perspective taken by Jeffrey Manber, one of the pioneers of the 21st-century spaceflight revolution, in a book tracing the roots of private-sector spaceflight to the French novelist.

“The first realistic steps taken in rocket development were because of a French science-fiction book,” Manber says in the latest episode of the Fiction Science podcast. “And that’s an underlying theme, in that we really needed a commercial ecosystem to get going. It’s not a government decree.”

The influence of Verne’s classic spaceflight novel, “From the Earth to the Moon,” continues to the present day: For example, when Bezos built the headquarters for his Blue Origin rocket venture, he brought in a Verne-inspired, Victorian-style rocket ship (complete with a cushy cockpit) to serve as the centerpiece of the building’s lobby.

Manber also pays tribute to Jules Verne in the title of his book series: “From the Earth to Mars.” He’s writing the story chapter by chapter, and the first two chapters recently came out as a 106-page volume.

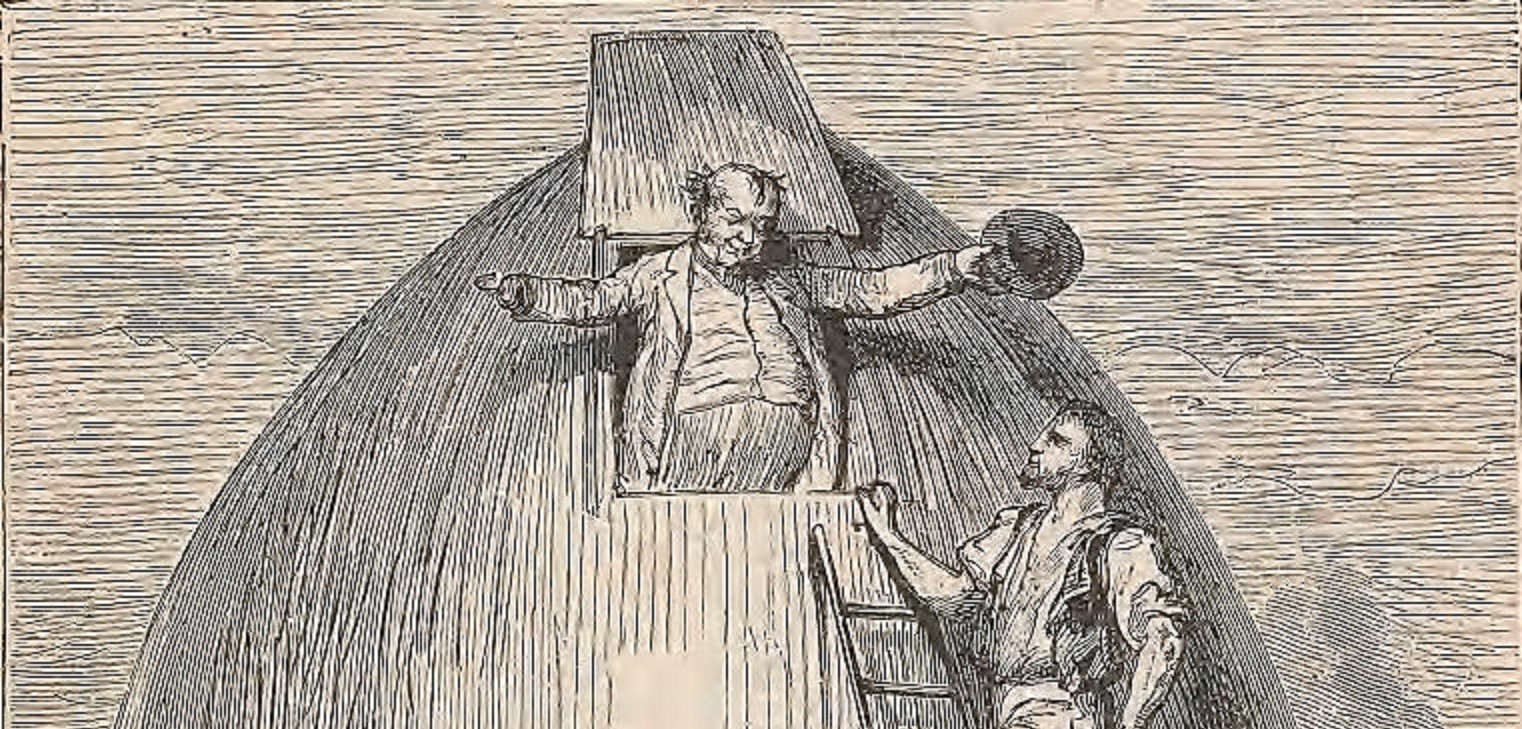

Verne’s story resonated with Manber for several reasons: First, the heroes of the story aren’t government employees, but members of a a group called the Baltimore Gun Club. They raise the money to build a giant gun as well as a projectile big enough for three club members to climb inside. A blastoff from Florida sends the trio on a thrilling ride to the moon and back, ending with a Pacific Ocean splashdown.

Manber loves the “eerie similarities” to NASA’s Apollo moon missions, but he’s even more impressed by the tale’s impact on early rocketeers.

Russian rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was so taken by the tale that he looked into whether a giant gun could actually fire a spaceship to the moon. He determined that it couldn’t, but went on to work out what’s now known as the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation. Tsiolkovsky also came up with the idea of using multistage rockets, with liquid oxygen and hydrogen as an option for propellants.

In his book, Manber traces the cross-fertilization that took place between Russian and German rocketeers, as well as between those rocketeers and science-fiction writers. For example, German rocket scientist Hermann Oberth collaborated with famed filmmaker Fritz Lang on a 1929 movie called “The Woman in the Moon,” based on Oberth’s ideas as well as a story written by Lang’s wife, Thea von Harbou. (You can watch the full movie on the Internet Archive, but skip the first 90 minutes to get to the good stuff.)

Once again, the connections between fiction and reality are eerie: During the making of the movie, Lang invented the second-by-second countdown as a device to heighten the drama of a rocket launch. He even tried to film an actual rocket launch for a scene in the movie. That idea fizzled out — but years after the movie was released, the Nazis recruited Oberth along with other technical advisers to work on their V-2 missile program. (They also banned showings of the movie and destroyed Lang’s rocket models, for fear they would expose secrets.)

“You can trace that to the V-2,” Manber said.

The first installment of “From the Earth to Mars” ends before the Nazis and the V-2 enter the picture. But future installments will address that dark chapter as well as the development of government-led space programs in Russia, the U.S. and China.

“I want people to know what our roots are, and it’s going to keep going all the way to the present,” Manber said.

Fast-forward to the future

Some of the narrative will surely draw upon Manber’s decades of personal experience in space commercialization. As the head of a company called MirCorp, he basically turned Russia’s Mir space station into a privately financed operation during its final days in 2000. A couple of years later, he came oh-so-close to sending boy-band singer Lance Bass to the International Space Station.

Manber was more successful with the space venture that followed, Nanoracks, which blazed a trail for commercial research and satellite deployment on the space station. Nanoracks and its current parent company, Voyager Space, arranged to have the Bishop Airlock added to the space station in 2021, marking another milestone for commercial space development. Today, Voyager Space and Nanoracks are part of an industry team that’s developing a commercial space station called Starlab with backing from NASA.

Manber has eased back on his corporate responsibilities — but last month, he was awarded NASA’s Distinguished Public Service Medal for “developing the foundation for the nascent commercial economy” in low Earth orbit through his work at MirCorp and Nanoracks. “I can take some solace that in space, with what we were handed, we’ve taken it and passed it along in better shape,” he said.

So, what about the next chapters in the real-life space saga? Manber offered a few predictions about the twists that are likely to lie ahead on the path from the Earth to Mars:

- The consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have shaken Manber’s faith in international space cooperation. U.S.-Russian cooperation is continuing on the International Space Station, but Manber doubts that will carry over to future projects. “Everything I worked on grinds to a halt, except for the ISS,” he said.

- Manber said U.S.-Chinese space cooperation seems more likely, despite longstanding limits on technological ties. “I understand very well the tensions in the South China Sea, the economic tensions, but there’s always that room for that thing called commercial,” he said. “I see no reason today, 2023, that we should not be doing commercial work in space with the Chinese.”

- If SpaceX can get its Starship super-rocket through testing and into operation, that would be a game-changer, Manber said. “In fact, it’s so much of a game-changer, I have concerns about monopolistic behavior,” he said. “I didn’t fight for 30, 40 years to make this a commercial marketplace, or a competition, to replace one single point with another, which would be SpaceX. … I like the dream. I like all that. But I want competition.”

- When will humans set foot on Mars? “I am a very cautious human being,” Manber said. “My cautious answer will be, I finally believe we will return to the moon and go on to Mars sooner than the pessimists believe.” But SpaceX and its CEO, Elon Musk, could force a radical change in Manber’s calculations. “I’ll put it to you this way,” he said. “If he gets Starship going in the next year or two, we’re going to Mars sooner than you and I think.”

Is there anyone who can take Jules Verne’s place for inspiring the next generation of innovators? Check out the original version of this report on Cosmic Log for Manber’s reading recommendations.

Visit FromTheEarthToMars.com to order Manber’s book and sign up for updates. And stay tuned for future episodes of the Fiction Science podcast via Apple, Google, Overcast, Spotify, Player.fm, Pocket Casts, Radio Public and Podvine. If you like Fiction Science, please rate the podcast and subscribe to get alerts for future episodes.

Verne famously once said about H. G. Wells’s “First Men on the Moon”, “I sent my characters to the moon with gunpowder, a thing one may see every day. Where does M. Wells find his cavorite? Let him show it to me!” I don’t know if Wells said that if Verne’s Space Gun was actually possible and did not blow itself apart on detonation, the people inside would have turn to bloody masses of jelly on ignition. I imagine that Tsiolkovsky knew this!