It’s official. Comet C/2014 UN271 (Bernardinelli-Bernstein) has the largest nucleus ever seen in a comet. The gargantuan comet was discovered in the fall of 2021, and in January 2022, astronomers turned the Hubble Space Telescope to ascertain more details and determine the exact size.

NASA said a team of scientists has now estimated the diameter is approximately 129 km (80 miles) across, making it larger than the state of Rhode Island. The nucleus is about 50 times larger than other known comets. Its mass is estimated to be a staggering 500 trillion tons, a hundred thousand times greater than the mass of a typical comet found much closer to the Sun.

“This is an amazing object, given how active it is when it’s still so far from the Sun,” said Man-To Hui of the Macau University of Science and Technology, Taipa, Macau, lead author on a new paper on the comet. “We guessed the comet might be pretty big, but we needed the best data to confirm this.” So, his team used Hubble to take five photos of the comet on January 8, 2022.

The comet was discovered Pedro Bernardinelli and Gary Bernstein, from the University of Pennsylvania. They were scouring through data from the 570-megapixel Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope in Chile. They found data of this object that was originally collected from 2014–2018, which did not show a typical comet tail, and the object was therefore thought to be a dwarf planet.

But within a day of the announcement of its discovery via the Minor Planet Center, astronomers using the Las Cumbres Observatory network took new images which revealed that it has grown a coma in the past 3 years, and that it was rapidly moving rapidly through the Oort Cloud. The object was then officially classified as a comet.

Then astronomers then began studying this comet in earnest, taking data from all sorts of previous and recent observational sources, intensively studied by ground and space-based telescopes.

C/2014 UN271 (Bernardinelli-Bernstein) is moving in the direction towards the Sun from the outer Solar System at about 35,400 kilometers per hour (22,000 mph) But, astronomers say, don’t worry. It will never get closer than 1.6 billion km (1 billion miles) away from the Sun, slightly farther than the distance of the planet Saturn. And that won’t be until the year 2031. And still, only large telescopes will be able to see it – it likely won’t be visible to the naked eye.

Credits: NASA, ESA, Man-To Hui (Macau University of Science and Technology), David Jewitt (UCLA); Image processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

As with any comet, the challenge comes in trying to measure the solid nucleus while it is enveloped in a huge dusty coma. While the comet is currently too far away for its nucleus to be visually resolved by Hubble, the data did show a bright spike of light at the nucleus’ location. Hui and his team next made a computer model of the surrounding coma and adjusted it to fit the Hubble images. Then, the glow of the coma was subtracted to leave behind the starlike nucleus.

The work of Hui and his team to constrain the diameter and reflectivity of the coma showed the actual measurements are quite close to the early estimates a size of 100-200 km, and low reflectivity. Astronomers described the nucleus as “blacker than coal.”

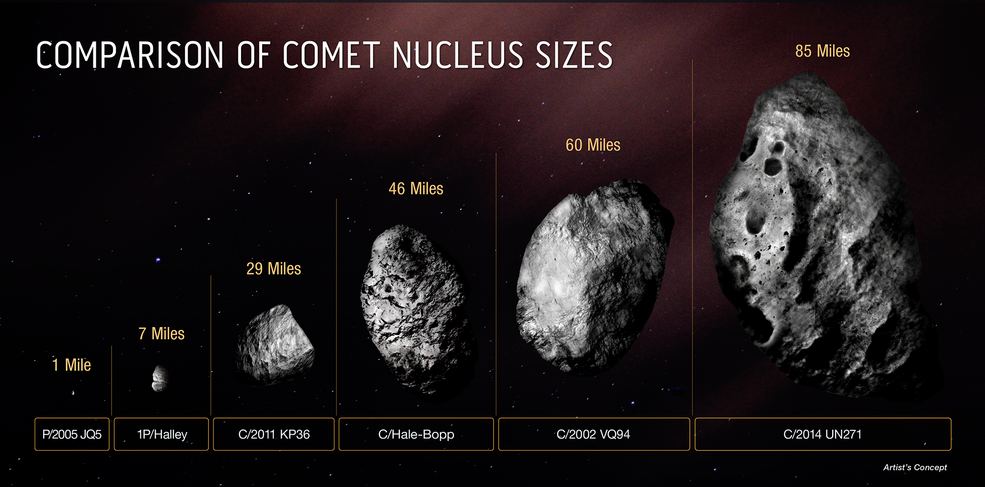

Previously, the largest comet ever measured was C/2002 VQ94, with a nucleus estimated to be 60 miles across. It was discovered in 2002 by the Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) project.

But there are probably more comets like this, with origins from the edge of the Solar System.

“This comet is literally the tip of the iceberg for many thousands of comets that are too faint to see in the more distant parts of the solar system,” said David Jewitt, a professor of planetary science and astronomy at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and co-author of the new study in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. “We’ve always suspected this comet had to be big because it is so bright at such a large distance. Now we confirm it is.”

Lead image caption:

This diagram compares the size of the icy, solid nucleus of comet C/2014 UN271 (Bernardinelli-Bernstein) to several other comets. The majority of comet nuclei observed are smaller than Halley’s comet. They are typically a mile across or less. Comet C/2014 UN271 is currently the record-holder for big comets. And, it may be just the tip of the iceberg. There could be many more monsters out there for astronomers to identify as sky surveys improve in sensitivity. Though astronomers know this comet must be big to be detected so far out to a distance of over 2 billion miles from Earth, only the Hubble Space Telescope has the sharpness and sensitivity to make a definitive estimate of nucleus size.Credits: Illustration: NASA, ESA, Zena Levy (STScI)

Further reading: NASA press release, paper in Astrophysical Journal, previous article on Universe Today on the comet’s discovery