You have to be careful what you say to people. When NASA or someone else says that the Perseverance rover will be looking for fossil evidence of ancient life, the uninformed may guffaw loudly. Or worse, they may think that scientists are looking for actual animal skeletons or something.

Of course, that’s not the case.

So what is Perseverance looking for?

Scientists who study Mars hope that Perseverance will find fossilized evidence of ancient microbial life. Mars was once wet and warm a long time ago, and those conditions may have been right for microbial life. But Martian habitability didn’t last long enough for complex animals to evolve. So no skeletons or dinosaur femurs sticking out of cliff faces.

Life on Earth started with simple creatures, and they left evidence of their time here. Microbialites are some of the most ancient evidence for life on Earth. If you’re familiar with the term stromatolites and understand how they fit in, stromatolites are just a type of microbialite with a layered structure.

Microbialite is the name given to the carbonate sediment structures created by ancient microbes. These fossilized structures on Earth are some of our most ancient evidence of life. They form as a result of photosynthetic cyanobacteria, and they date back to the Precambrian.

Scientists think that if life did appear on Mars, it likely never evolved past the microbe stage. There wasn’t enough time. But that doesn’t mean that microbes left no fossil evidence.

This is one of the prime reasons that Perseverance was sent to Jezero Crater. Jezero is an ancient paleolake, and it holds large sediment deposits carried in by water. Those ancient deposits could hold fossilized evidence of life. Earth’s ancient stromatolites are found along shorelines, and Jezero’s ancient, 3.5 billion-year-old shorelines may hold similar evidence.

It’s unlikely that Perseverance will find actual stromatolites, or their Martian equivalent. But certain types of minerals in Jezero Crater may hold fossilized evidence or biosignatures of ancient life. Much of that evidence could be microscopic.

“We expect the best places to look for biosignatures would be in Jezero’s lakebed or in shoreline sediments that could be encrusted with carbonate minerals, which are especially good at preserving certain kinds of fossilized life on Earth,” said Ken Williford, deputy project scientist for the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover mission at JPL. “But as we search for evidence of ancient microbes on an ancient alien world, it’s important to keep an open mind,” he said in a press release.

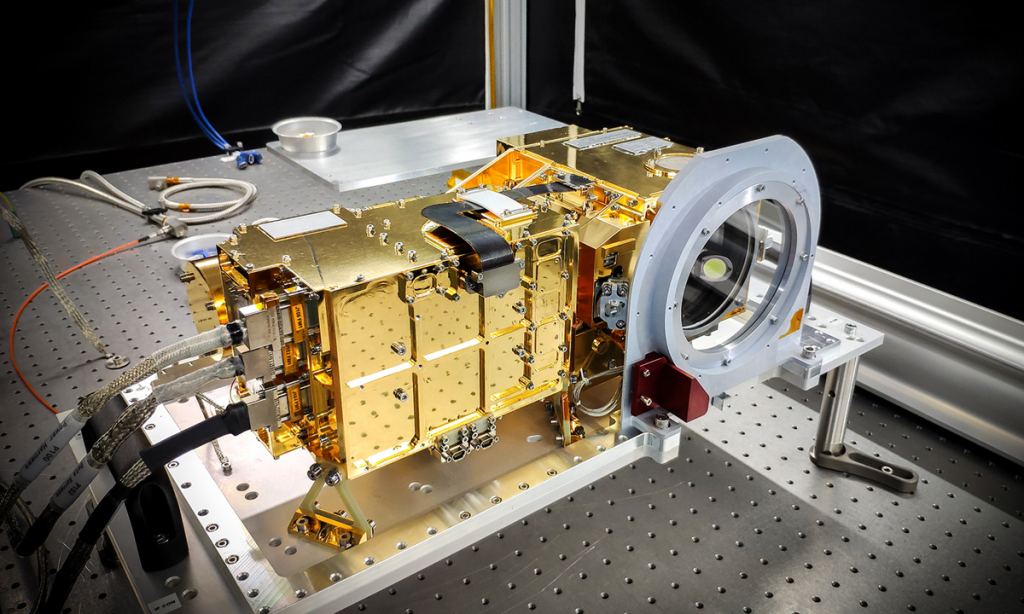

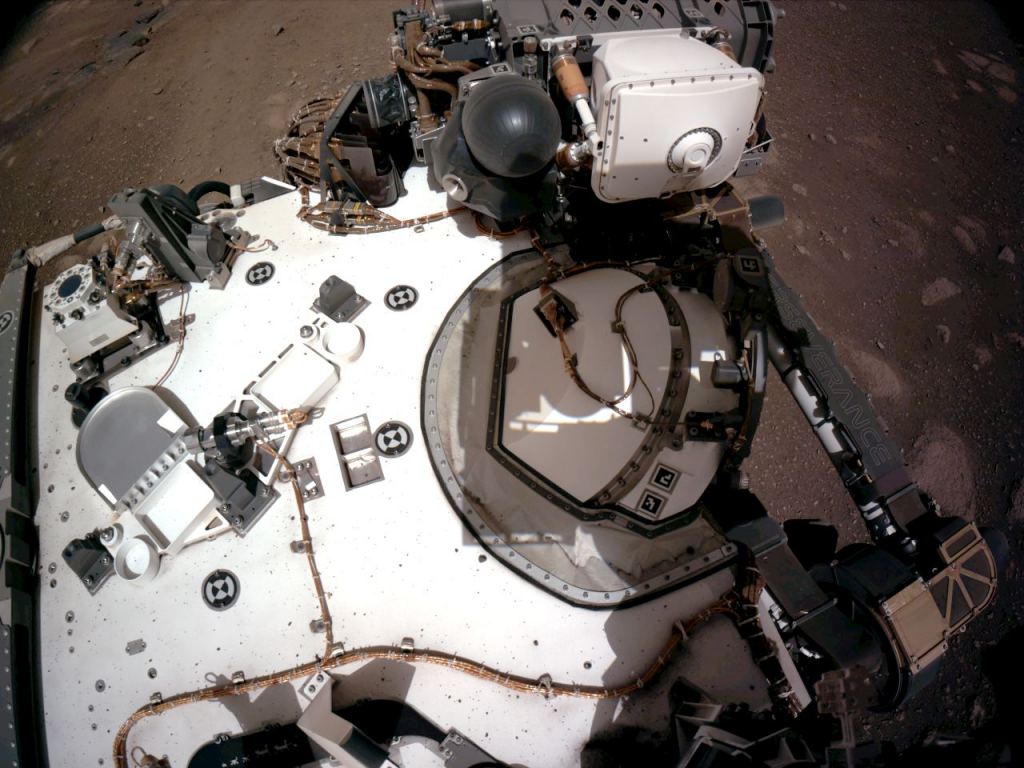

While Perseverance has several scientific goals, the search for ancient life is of prime importance. To seek it out, the sophisticated rover carries a suite of instruments. Chief among them might be the rover’s SuperCam.

SuperCam uses a camera, a laser, and spectrometers to examine rocks on Mars. The laser has enough energy to reach about 7 meters (20 ft) and turn a small amount of its rock target into plasma. The spectrometers then read the light that passes through the plasma to measure its components.

The science team is looking for minerals and organic molecules that could only have formed in watery environments. They’ll assess the results from all of the rover’s instruments and decide what to do next. Depending on the results, the rover can then go in for a closer look and even take a sample with its drill. One of Perseverance’s remarkable features is that it can identify targets on its own using AI and can decide to use the laser and spectrometer if it finds an enticing target.

“Yes, there are certain shapes that form in rocks where it’s extremely difficult to imagine an environment devoid of life that could cause that shape to form,” said Williford. “But that said, there are chemical or geologic mechanisms that can cause domed layered rocks like we typically think of as a stromatolite.”

If the rover spotted something similar to an Earthly stromatolite, for instance, then it would be compelling evidence indeed. But most likely, the sample would have to be returned to Earth before anything could be really truly confirmed.

While Perseverance is an inspiring technological marvel it still has its limitations. There’s simply no way to send to Mars the kind of lab equipment needed to examine samples and confirm any evidence of microbial life.

“The instrumentation required to definitively prove microbial life once existed on Mars is too large and complex to bring to Mars,” said Bobby Braun, the Mars Sample Return program manager at JPL. “That is why NASA is partnering with the European Space Agency on a multi-mission effort, called Mars Sample Return, to retrieve the samples Perseverance collects and bring them back to Earth for study in laboratories across the globe.” Sadly, that’s probably about a decade away.

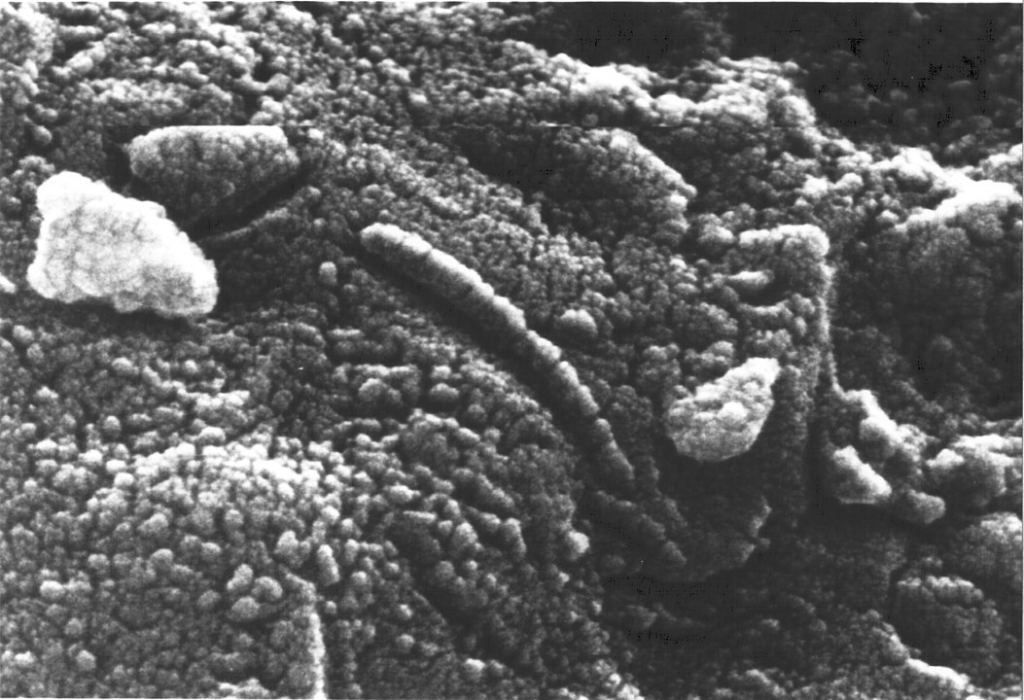

We all need to tread carefully here. In the past, there’s been evidence from Mars that looked like it had biogenic features. The Alan Hills meteorite was discovered in the Antarctic in 1984. It’s a 4 billion-year-old rock that came from Mars when an impact on that planet sent rocks into space. Eventually, that meteorite landed here.

Researchers said that the meteorite contained evidence of ancient life. It contained minerals and carbon compounds that are produced by microbes here on Earth. Electron microscope images showed globule-shaped chain-like features that are also produced by Earthly microbes.

Some claimed that this was indeed evidence of life on Mars. Scientist David McKay of NASA’s Johnson Space Center said at the time that “We believe that these are indeed microfossils from Mars.” And Paleobiologist J. William Schopf said, “I’ll show you the oldest evidence of life on this planet,” when he showed slides of the meteorite to an audience.

But those claims were very controversial. Eventually, Carl Sagan’s famous statement that “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” calmed things down. Over time, rigorous scientific scrutiny rejected the meteorite as evidence of ancient Martian life, as the rock’s interesting features were shown to have abiotic origins.

The Alan Hills Meteorite was an important cautionary episode in the study of Mars. It led to greater caution when interpreting evidence from Mars. That caution will come in handy during Perseverance’s mission.

We’re all hoping for a knockout blow from Perseverance. We’re all hoping for unequivocal evidence that life existed on Mars. We’re all hoping for a big announcement by NASA one day.

But science is incremental, and instead, we may have to wait a long time. If there was once life on Mars, the evidence showing it might come in bit by bit, as the story is revealed. We may get tantalizing glimpses of that evidence, thanks to Perseverance’s surface operations.

But it seems more likely that we’ll have to wait until the samples are returned, and the real, in-depth scientific scrutiny can begin. Then, at some point in the future, maybe, we can finally know.

More:

- Press Release: Searching for Life in NASA’s Perseverance Mars Samples

- Press Release: NASA Moves Forward With Campaign to Return Mars Samples to Earth

- Smithsonian Magazine: Life on Mars?

- Universe Today: Watch Perseverance Land on Mars. Mind…Blown