While astronomers are trying to figure out which planets they find are habitable, there are a range of things to consider. How close are they to their parent star? What are their atmospheres made of? And once those answers are figured out, here’s something else to wonder about: how many minerals are on the planet’s surface?

In a talk today, the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Robert Hazen outlined his findings showing that two-thirds of minerals on Earth could have arisen from life itself. The concept is not new — he and his team first published on that in 2008 — but his findings came before the plethora of exoplanets discovered by the Kepler space telescope.

As more information is learned about these distant worlds, it will be interesting to see if it’s possible to apply his findings — if we could detect the minerals from afar in the first place.

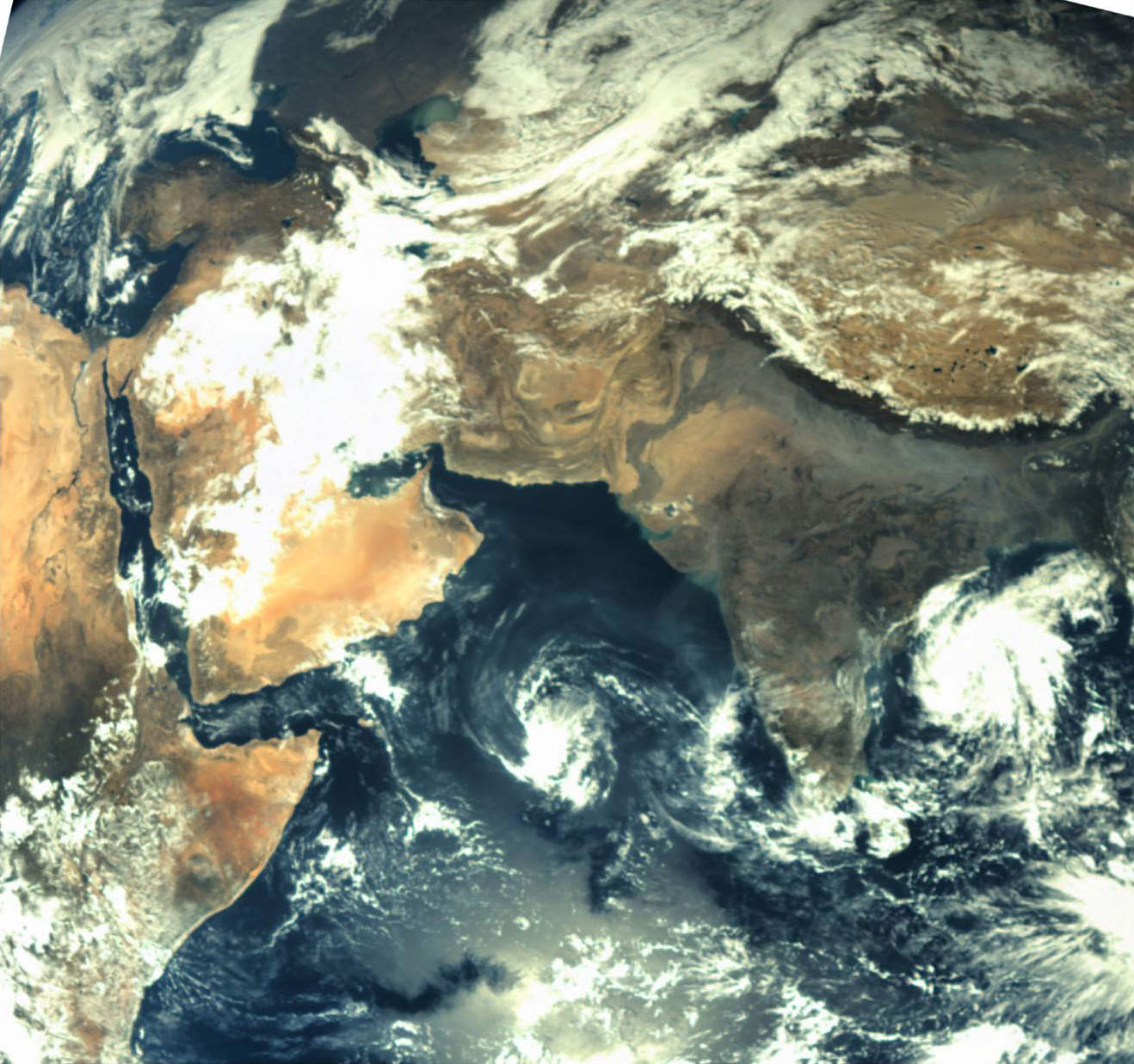

“We live on a planet of remarkable beauty, and when you look at it from the proximity of our moon, you see what is obviously a very dynamic planet,” Hazen told delegates at “Habitable Worlds Across Time and Space”, a spring symposium from the Space Telescope Science Institute that is being webcast this week (April 28-May 1).

His point was that planets don’t necessarily start out that way, but he said in his talk that he’d invite comments and questions on his work for alternative processes. His team believes that minerals and life co-evolved: life became more complex and the number of minerals increased over time.

The first mineral in the cosmos was likely diamonds, which were formed in supernovas. These star explosions are where the heavier elements in our cosmos were created, making the universe more rich than its initial soup of hydrogen and helium.

There are in fact 10 elements that were key in the Earth’s formation, Hazen said, as well as that of other planets in our solar system (which also means that presumably these would apply to exoplanets). These were carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, magnesium, silicon, carbon, titanium, iron and nitrogen,which formed about a dozen minerals on the early Earth.

Here’s the thing, though. Today there are more than 4,900 minerals on Earth that are formed from 72 essential elements. Quite a change.

Hazen’s group proposes 10 stages of evolution:

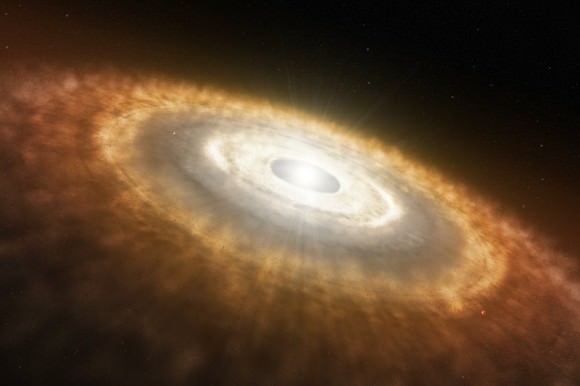

- Primary chondrite minerals (4.56 billion years ago) – what was around as the solar nebula that formed our solar system cooled. 60 mineral species at this time.

- Planetesimals — or protoplanets — changed by impacts (4.56 BYA to 4.55 BYA). Here is where feldspars, micas, clays and quartz arose. 250 mineral species.

- Planet formation (4.55 BYA to 3.5 BYA). On a “dry” planet like Mercury, evolution stopped at about 300 mineral species, while “wetter” planets like Mars would have seen about 420 mineral species that includes hydroxides and clays produced from processes such as volcanism and ices.

- Granite formation (more than 3.5 BYA). 1,000 mineral species including beryl and tantalite.

- Plate tectonics (more than 3 BYA). 1,500 mineral species. Increases produced from changes such as new types of volcanism and high-pressure metamorphic changes inside the Earth.

These stages above are about as far as you would get on a planet without life, Hazen said. As for the remaining stages on Earth, here they are:

- Anoxic biosphere (4 to 2.5 BYA), again with about 1,500 mineral species existing in the early atmosphere. Here was the rise of chemolithoautotrophs, or life that obtains energy from oxidizing inorganic compounds.

- Paleoproterozoic oxidation (2.5 to 1.5 BYA) — a huge rise in mineral species to 4,500 as oxygen becomes a dominant player in the atmosphere. “We’re trying to understand if this is really true for every other planet, or if there is alternative pathways,” Hazen said.

And the final three stages up to the present day was the emergence of large oceans, a global ice age and then (in the past 540 million years or so) biomineralization or the process of living organisms producing minerals. This latter stage included the development of tree roots, which led to species such as fungi, microbes and worms.

It should be noted here that oxygen does not necessarily indicate there is complex life. Fellow speaker David Catling from the University of Washington, however, noted that oxygen rose in the atmosphere about 2.4 billion years ago, coincident with the emergence of complex life.

Animals as we understand them could have been “impossible for most of Earth’s history because they couldn’t breathe,” he noted. But more study will be needed on this point. After all, we’ve only found life on one planet: Earth.

The STSCI conference continues through May 1; you can see the agenda here.

Only if ‘coincident’ means ‘off with 1.2 billion years’ or ‘highly uncertain date’. Eukaryotes may not have evolved mitochondrial endosymbionts until 1.2 billion years ago, and complex multicellular such sometime after. Multicellularity seems to evolve easily, it has evolved 20+ independent times, 2 times evolved in the lab within 1 year, and is independent of oxygen. Complexity (many differentiated cells; body plans) relies on high energy density cells from using oxygen, for evolving large genomes with high protein turnover.

““When you are talking about these really ancient events, scientists have estimated numbers that are all over the board,” said coauthor Patrick Shih. Estimates of the age of eukaryotes – cells with a nucleus that evolved into all of today’s plants and animals – range from 800 million years ago to 3 billion years ago.

“We came up with a novel way of decreasing the uncertainty and increasing our confidence in dating these events,” he said. The two researchers believe that their approach can help answer similar questions about the origins of ancient microscopic fossils.

Shih and colleague Nicholas Matzke, who will earn their Ph.Ds this summer in plant and microbial biology and integrative biology, respectively, employed fossil and genetic evidence to estimate the dates when bacteria set up shop as symbiotic organisms in the earliest one-celled eukaryotes. They concluded that a proteobacterium invaded eurkaryotes [sic] about 1.2 billion years ago, in line with earlier estimates.”

[ https://newscenter.berkeley.edu/2013/06/19/scientists-date-prehistoric-bacterial-invasion-still-present-in-todays-cells/ ]