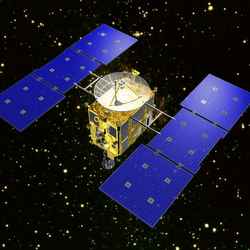

Hayabusa Muses-C. Image credit: ISAS Click to enlarge

With a maneuver that scientists compared to landing a jumbo jet in a moving Grand Canyon, Japan’s asteroid explorer, Hayabusa, touched down on the surface of the asteroid Itokawa Saturday for the second time in a week and this time it successfully collected a sample of the surface soils, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) announced several hours after its bird had flown.

The world’s first mission to attempt to land on an asteroid, collect samples, and return them to Earth has completed what is, arguably, the most difficult challenge on its agenda, and will begin the long journey back to Earth in early December. If all goes as planned, the sample will be returned in a capsule slated to land in the Australian outback in June 2007.

Every command necessary for the sampling was carried out, JAXA announced Saturday evening Japan Standard Time (JST) on its website, and agency officials firmly believe that the mission succeeded in the world’s first collection of samples of surface materials from an asteroid. It is highly probable, according to the agency, that the asteroid explorer has snatched several grams of surface samples from the near Earth asteroid named after the “father” of Japan’s space program, Hideo Itokawa, but the exact volume will not be known until the spacecraft returns safely to Earth.

The spacecraft was on its own once it began to carry out the series of commands for Saturday’s touch-down, because signals take around 17 minutes to get from Earth to Hayabusa. The spacecraft’s autonomous navigation relies on the Optical Navigation Camera and Light Detection and Ranging (ONC/LD&R) instrument that measures the distance to and the shapes of the asteroid surface. Once the data from those and other instruments are fully analyzed, more specific details will be forthcoming.

Hayabusa which means “falcon” in Japanese — flew up and away from the asteroid after snatching its prey, and was subsequently “restored” by its ground team and instructed to return to its home orbit around 7 kilometers away from the asteroid. Japan, meanwhile, is soaring into space exploration history with a flight that has provided a stellar boost for the Japanese space program, and cause for major celebration in the homeland.

“This is a superb achievement, a great moment is space exploration,” said Planetary Society Executive Director Louis D. Friedman. “Automated surface sample return from another world has been done only from the Moon, and only by the Russians. This venture by the Japanese space agency is bold, and Hayabusa has been brilliantly executed mission.”

Hayabusa which was developed at the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), a space science research division of JAXA — launched from Japan’s Kagoshima Space Center on May 9, 2003 and arrived in September of this year despite being rocked on the way by several solar flares, and losing one of its three reaction wheels used to control the spacecraft’s orientation, point instruments, antennas, or subsystems at chosen targets.

Since then it has met with other misfortunes, including the loss of another reaction wheel and the loss of its tiny robot lander, Minerva, which it released at the wrong time. Still, from every mishap, Hayabusa has rebounded. “It’s the little spacecraft that could,” marveled Donald K. Yeomans, senior research scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the U.S. project scientist for the mission during an interview with The Planetary Society. “And the operations guys are working their tails off around the clock.”

The touch-down landing Saturday was Hayabusa’s second and final attempt to collect a sample from the small asteroid, which, according to the latest Japanese measurements is only 540 meters by 310 meters by 250 meters (about 1800 feet by 1000 feet by 820 feet), and is some 180 million miles from Earth. Although the spacecraft did bounce down twice and even settled on Itokawa’s surface for 30 minutes last weekend — marking a milestone as the first Japanese spacecraft to land on an extraterrestrial body — the sample collection device did not deploy, so that attempt to get a sample failed.

This time around, Hayabusa began its descent around 10:00 p.m., JST, Friday, November 25. By 7:15 a.m., the following morning, it was just 14 meters above Itokawa. At around 8:45 a.m., at least one tantulum pellet was fired through the cylinder in the sample collection device and into the surface at 300 meters per second and the ejecta from that cratering effect was captured and secured in the sample chamber.

The handful of dirt and dust that Hayabusa snatched Saturday may seem a small prize for all the effort, but the knowledge these samples hold about our solar system is by all accounts great. Asteroids preserve in their make-up the pristine materials that went into formation of the solar system, unlike the Moon or other larger planetary bodies that have undergone thermal alterations over the eons.

Hayabusa is “the next giant step forward” in understanding the role of near-Earth asteroids in the origin of the solar system, their potential threat to Earth, and the future use of their raw materials to expand human presence beyond Earth, according to Yeomans. “Near Earth asteroids are easier to land on than the Moon itself, some of them, and they’re far more rich in minerals,” he pointed out. “If you’re going to build structures in space, you’re not going to build them on the ground and launch them, you’re going to look for raw materials up there and asteroids provide some ready supplies of minerals, metals, and possibly water.”

Perhaps even more remarkable than Hayabusa’s achievements is the fact that the Japanese have pulled this mission off for a price tag of about $170-million-dollars [about one-third the cost of a NASA Discovery mission], and with a small mission operations team at the helm. “That is extraordinary,” said Yeomans.

Before the mission launched, Yeomans and others at JPL and NASA provided JAXA and ISAS division, with the ephemeris, a table that shows the coordinates of a celestial body at a number of specific times during a given period — essentially “directions” on how to get to the asteroid. NASA is tracking the spacecraft with the Deep Space Network (DSN) and the Americans there are providing some back-up navigation assistance. However, Hayabusa is not relying on NASA for navigation. In Yeomans’ words: “Since the spacecraft arrived at the asteroid it, has been Japan’s show.”

And what a show it’s been.

Original Source: NASA Astrobiology