Following the Moon lately? The up and coming Full Moon is the most famous of them all, as we approach the Harvest Moon for 2018. Continue reading “Heralding the 2018 Harvest Moon”

This Weekend: A Hunter’s Full Moon Kicks Off Supermoon Season

Ready for some lunar action of proxigean proportions? This weekend’s Full Moon ushers in that most (infamous?) of internet ready cultural memes: that of the Supermoon. This moniker stands above the Blood, Mini, and Full Moons both Black and Blue as the Full Moon of the year that folks can’t seem to get enough of, and astronomers love to hate.

But wait a minute: is this weekend’s Full Moon really the closest of the year?

Nope, though it’s close. But this month’s Full Moon does, however, usher in what we like to call Supermoon season.

Let us explain.

First, we’ll let you in on the Supermoon’s not so secret history. Yes, the meme arose over the last few decades, mostly due to the dastardly deeds of astrologers. Y’know, that well meaning friend/coworker/relative/anonymous person on Twitter that constantly mistakes your passion for the night sky as ‘astrology.’ Anyhow, the idea of the Supermoon has gained new life via the internet, and loosely translates as the closest Full Moon of the year. Sometimes, its dressed up with the slightly science-y sounding ‘a Full Moon along the closest 90% of its orbit’ (!) definition.

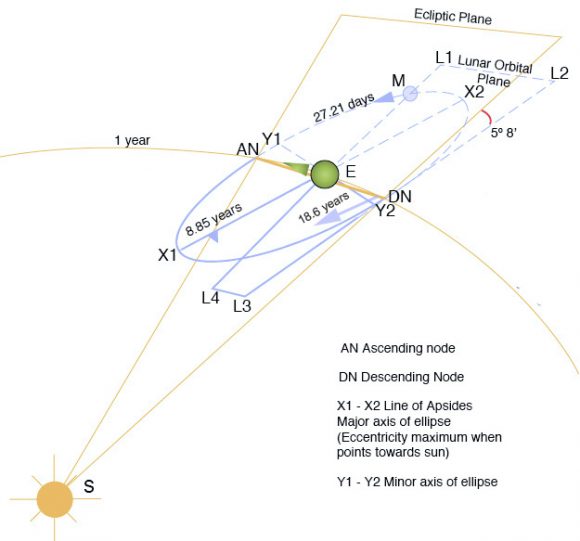

Now, to know the orbit of the Moon is to understand celestial mechanics. The Moon’s orbit is indeed elliptical, ranging from an average perigee (its closest point to the Earth) of 362,600 kilometers, to an apogee of 405,400 kilometers distant.

Fun fact: the time it takes the Moon to go from one perigee to the next (27.55 days) is one anomalistic month, a fine pedantic point to bring up to said relative/coworker the next time they refer to you as an astrologer.

And yes, the perigee Full Moon is a thing. We even like to throw about the quixotic term of the proxigean Moon, a time when tidal variations are at an extreme. Plus, all perigees are not created equal, but range from 356,400 kilometers to 370,400 kilometers distant, as the Earth-Moon system not only swings around its common barycenter, but the Sun also drags the entire orbit of the Moon around the Earth, completing one complete revolution every 8.85 years in what’s known as the precession of the line of apsides. Note that the nodes of the Moon’s orbit actually move in the opposite direction, with an 18.6 year period.

Yup, the motion of the Moon has given humanity a fine study in Celestial Mechanics 101. Anyhow, we contend that a more succinct definition for a perigee ‘Supermoon’ is simply a Full Moon that falls within 24 hours of perigee. Under this definition, the Full Moon this Sunday on October 16th occurring at 4:23 Universal Time (UT) certainly meets the criterion, occurring 19 hours and 24 minutes before perigee… as does the Full Moon of November 14th (2.4 hours from perigee) and December 13th (just under 24 hours from perigee).

For extra fun, said November 14th perigee Full Moon is the closest in 30 years; expect Supermoon lunacy to ensue.

A fun place to play with Full and New Moons vs perigee and apogee past present and future is Fourmilab’s Lunar Apogee and Perigee Calculator. Hey, it’s what we do for fun. Looking over these cycles, you’ll notice a pattern of ‘supermoon seasons’ emerge, which moves forward along the calendar about a lunation a year. (that’s our friend the precession of the line of apsides at work again).

(another fun fact: the time it takes for the Moon to return to a similar phase—for example, Full back to Full—is 29.5 days, and known as a synodic month.)

The Full Moon does appear slightly larger at perigee than apogee, to the tune of 29.3′ versus 34.1′ across. This change is enough to notice with the unaided eye, though the Moon is deceptively smaller than it appears: you could, for example, line up 654 ‘Supermoons’ around the local horizon from end to end.

The October Moon is also referred to by the Algonquin Native Americans as the ‘Hunter’s Moon,’ a time to use that extra illumination to track down vital sustenance as the harsh winter approaches. Very occasionally, the Harvest Full Moon falling near the September southward equinox falls in early October (as occurs next year in 2017) and bumps the Hunter’s Moon from its monthly slot.

Be sure to stalk the rising Hunter’s Moon near perigee this weekend. Of course, we’ll be shooting at our prey with nothing more than a camera, as the Full Moon rises from behind the Andalusian foothills.

What is a Hunter’s Moon?

If you live in the northern hemisphere, than stargazing during the early autumn months can a bit tricky. During certain times in these seasons, the stars, planets and Milky Way will be obscured by the presence of some very beautiful full moons. But if you’re a fan of moongazing, then you’re in luck.

Because it is also around this time (the month of October) that people looking to the night sky will have the chance to see what is known as a Hunter’s Moon. A slight variation on a full moon, the Hunter’s Moon has long been regarded as a significant event in traditional folklore, and a subject of interest for astronomers.

Definition:

Also known as a sanguine or “blood” moon, the term “Hunters Moon” is used traditionally to refer to a full moon that appears during the month of October. It is preceded by the appearance of a “Harvest Moon”, which is the full moon closest to the autumnal equinox (which falls on the 22nd or 23rd of September).

The Hunter’s Moon typically appears in October, except once every four years when it doesn’t appear until November. The name dates back to the First Nations of North America. It is so-called because it was during the month of October, when the deers had fatted themselves over the course of the summer, that hunters tracked and killed prey by autumn moonlight, stockpiling food for the coming winter.

Characteristics:

Although typically the Moon rises 50 minutes later each day, things are different for the Hunter’s Moon (as well as the Harvest Moon). Both of these moons usually rise 30 minutes later on each successive night, which means that sunset and moonrise are not far apart.

This means there is prolonged periods of light during this time of the the year, which is the reason why these moons have traditionally been used by hunters and farmers to finish their work.

This difference between the timing of the sunset and moonrise is due to its orbit, meaning that the angle the Moon makes with the horizon is narrower during this time of year. The Hunter’s Moon is generally not bigger or brighter than any of the other full moons. Thus, the only difference between it and other full moons is the that the time between sunset and moonrise is shorter.

History of Observation:

Because the approach of winter signaled the possibility of going hungry in pre-Industrial times, the Hunter’s Moon was generally accorded with special honor, historically serving as an important feast day in both northern Europe and among many Native American tribes.

Traditionally, Native American hunters used the full moon of October to stalk deer and to spot foxes at night as they prepared for the coming winter. Because the fields were traditionally reaped in late September or early October, hunters could easily see foxes and other animals that came out to glean from the fallen grains.

The Hunter’s Moon is accorded similar significance in Europe, where it was also seen as a prime time to hunt during the post-harvest, pre-winter period when conditions were optimal for spotting prey. However, the term did not enter into usage for Europeans until after they made contact with Indigenous Americans and began colonizing North America.

The first recorded mentions of a “Hunter’s Moon” began in the early 18th century. The entry in the Oxford English Dictionary for “Hunter’s Moon” cites a 1710 edition of The British Apollo, where the term is attributed to “the country people”. The names are now referred to regularly by American sources, where they are often popularly attributed to “the Native Americans”.

In India, the harvest festival of Sharad Purnima, which marks the end of the monsoon season, is celebrated on the full moon day of the lunar month of Ashvin (September-October). There is a traditional celebration of the moon during this time that is known as the “Kaumudi” celebration – which translated, means “moonlight”.

Interesting Facts:

Sometimes, the Harvest Moon is mistaken for the Hunter’s Moon because once every four years or so the Harvest Moon is in October instead of September. When that happens, the Hunter’s Moon is in November. Traditionally, each month’s full moon has been given a name, although these names differ according to the source.

Other full moons of interest include the Wolf Moon in January, the Strawberry Moon in June, the Sturgeon Moon in August, the Cold Moon in December, and the Pink Moon in April. All of the full moons have different characteristics due to the location of the ecliptic – i.e. the path of the Sun – at the time of each.

The Hunter’s Moon is also associated with feasting. In the Northern Hemisphere, some Native American tribes and some places in Western Europe held a feast day. This feast day, the Feast of the Hunter’s Moon, was not been held since the 1700’s. However, the Feast of the Hunters’ Moon is a yearly festival in Lafayette, Indiana, which has been held in late September or early October every year since 1968.

We have many interesting articles about the moon here at Universe Today. For example, here are some about the red moon and a rundown of what a full moon is all about.

For more information, check out the page on the Hunter’s Moon at NightSkyInfo, and full moon names and meanings, courtesy of the Farmer’s Almanac.

Astronomy Cast has an interesting episode on the subject – Episode 113: The Moon: Part I

Sources:

Stunning Photos of the Hunter’s Moon Lunar Eclipse

Did you see it? On October 8, 2014, early risers in North and South America, east Asia, Australia and the Pacific saw unique and rare views of the Hunter’s Moon as was eclipsed by Earth’s shadow. We’ve got so many great pictures to share from our Flickr group and from social media! In some shots, the fully eclipsed Moon glows with a coppery red hue, and in others the partially eclipsed Moon appears to have a bite taken out of its bright surface. Some images pair the Moon with a faint planet Uranus.

This is the second and final total lunar eclipse of 2014, and the second of four in a quartet series of lunar eclipses known as a tetrad — a series of 4 consecutive total eclipses occurring at approximately six month intervals. The next total eclipse will be on April 4, 2015, with another occurring on Sept. 28, 2015.

Enjoy the images below!

Huffman Dam, Dayton, Ohio

Canon 6D, 80mm refractor,2x Barlow (1200mm) ISO 6400,

2 sec exposure. Credit and copyright: John Chumack/Galactic Images.

@Nancy_A I managed to see it and got a pic after clouds and snow got out of the way in Jellicoe Ont. pic.twitter.com/TiHDLGxwCM

— Bill Magee (@88skywatcher88) October 8, 2014

@fcain @starstryder these photos were taken on my phone with a 11 inch dobsonian telescope at the Perth Observatory pic.twitter.com/xhqnNalpqM

— Matt Woods (@matty_woods) October 8, 2014

#BloodMoon at treetops 08OCT2014, 06:25:25 EST! @universetoday @CanonUSA @triadlivingmag @WFMY @WXII @weatherchannel pic.twitter.com/9Kz1yVCVGn

— J Farley Photography (@jfarleyphoto) October 8, 2014

Want to get your astrophoto featured on Universe Today? Join our Flickr group or send us your images by email (this means you’re giving us permission to post them). Please explain what’s in the picture, when you took it, the equipment you used, etc.

This Week’s Penumbral Lunar Eclipse and the Astronomy of Columbus

You can always count on an eclipse to get you out of a delicate situation. Today is Columbus Day in the United States and Thanksgiving north of the border in Canada. Later this week also marks the start of the second eclipse season for 2013. Today, we thought we’d take a look at the circumstances for the first eclipse of the season kicking off this coming Friday night, October 18, as well as the fascinating role that eclipses played in the life and times of Christopher Columbus.

Friday’s event is a penumbral lunar eclipse, meaning that the Full Moon will only pass through the outer bright rim of the Earth’s shadow. Such events are subtle affairs, as opposed to total and partial lunar eclipses, which occur when the Moon enters the dark inner core, or umbra, of the Earth’s shadow. Still, you may just be able to notice a slight dusky shading on the lower southern limb of the Moon as it flirts with the umbra, barely missing it around the time of central eclipse at 23:51 Universal Time/ 7:51 PM Eastern Daylight Saving Time. Friday night’s penumbral is 3 hours and 59 minutes in duration, and 76.5% of the disk of the Moon will be immersed in the penumbra at maximum eclipse.

Key Events occurring on Friday, October 18th:

21:50UT/5:50PM EDT: 1st contact with the Earth’s shadow.

23:51UT/7:51PM EDT: Mid-eclipse.

01:49UT(Oct 19th)/9:49PM EDT: Last contact. Eclipse ends.

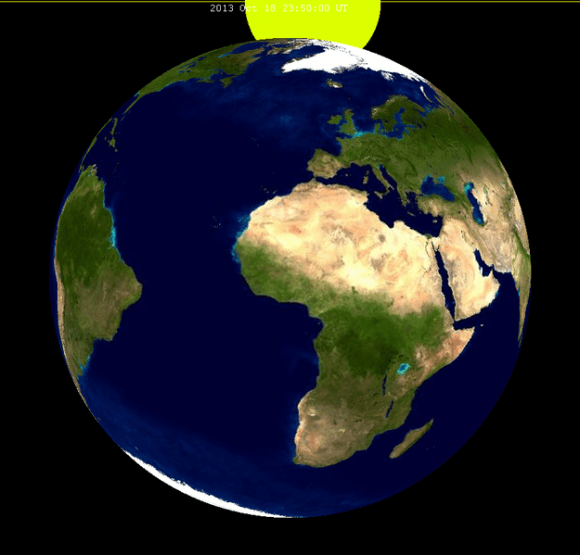

The eclipse will be underway at moonrise for North and South America and occur at moonset for central Asia— Africa and Europe will see the entire eclipse. Standing on Earth’s Moon, an observer on the nearside would see a partial solar eclipse.

This eclipse is the 3rd and final lunar eclipse of 2013, and the 5th overall. It’s also the first in a series of four descending node eclipses, including the total lunar eclipse of October 8th next year. It’s also the 52nd eclipse of 72 in the lunar saros series 117, which started on April 3rd, 1094 and will end with a final lunar eclipse on May 15th, 2356. Saros 117 produced its last total lunar eclipse in 1815 and its final partial in 1941.

Though penumbrals are slight events, we’ve been able to notice an appreciable difference before, during and after the eclipse photographically:

Be sure to use identical exposure settings to catch this effect. Locations where the Moon rides high in the sky also stand the best chance of imaging the faint penumbral shading, as the Moon will be above the discoloring effects of the thicker air mass low to the horizon.

The Moon reaches descending node along the ecliptic about 20 hours after the end of the eclipse, and reaches apogee just over six days later on October 25th. The October Full Moon is also known as the Hunter’s Moon, providing a bit of extra illumination on the Fall hunt.

And this sets us up for the second eclipse of the season the next time the Moon crosses an ecliptic node, a hybrid (annular-total) solar eclipse spanning the Atlantic and Africa on November 3rd. More to come on that big ticket event soon!

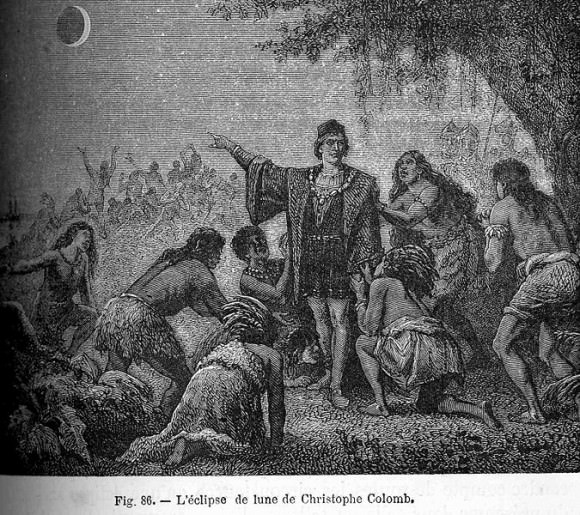

In Columbus’s day, the Moon was often used to get a rough fix of a ship’s longitude at sea. Columbus was especially intrigued with the idea of using lunar eclipses to determine longitude. If you can note the position of the Moon in the sky from one location versus a known longitude during an event— such as first contact of the Moon with the Earth’s umbra during an eclipse —you can gauge your relative longitude east or west of the point. The sky moves 15 degrees, or one hour of right ascension overhead as we rotate under it. One of the earliest records of this method comes to us from Ptolemy, who deduced Alexander the Great’s position 30 degrees (2 hours) east of Carthage during the lunar eclipse of September 20th, 331 B.C. Alexander noted that the eclipse began two hours after sunset from his locale, while in Carthage it was recorded that the eclipse began at sunset.

Columbus was a student of Ptolemy, and used this method during voyages to and from the New World during the lunar eclipses of September 14th, 1494 and February 29, 1504. Of course, such a method is only approximate. The umbra of the Earth often appears ragged and indistinct on the edge of the lunar disk at the start of an eclipse, making it tough to judge the actual beginning of an eclipse by more than ten of minutes or so. And remember, you’re often watching from the pitching deck of a ship to boot!

Another problem also plagued Columbus’s navigation efforts: he favored a smaller Earth than we now know is reality. Had he listened to another Greek astronomer by the name of Eratosthenes, he would’ve gotten his measurements pretty darned close.

An eclipse also saved Columbus’s butt on one occasion. The story goes that tensions had come to a head between the locals and Columbus’s crew while stranded on the island of Jamaica in 1504. Noting that a lunar eclipse was about to occur on March 1st (the evening of February 29th for North America), Columbus told the local leader that the Moon would rise “inflamed with wrath,” as indeed it did that night, right on schedule. Columbus then made a great show of pretending to pray for heavenly intersession, after which the Moon returned to its rightful color. This kept a conniving Columbus and his crew stocked in supplies until a rescue ship arrived in June of that year.

Be sure to check out this Friday’s penumbral eclipse, and amaze your friends with the prediction of the next total lunar eclipse which occurs on U.S. Tax Day next year on April 15th, 2014. Can you do a better job of predicting your longitude than Columbus?

Weekly SkyWatcher’s Forecast: October 29 – November 4, 2012

Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! Are you ready for some spooky targets this week? Then follow along as we take a look at the “Little Eyes”, the “Skull Nebula” and a star that’s as red as a drop of blood! If the weather permits, we’ll also be enjoying the Taruid Meteor Shower! Time to dust off those optics and meet me in the backyard…

Monday, October 29 – October’s Full Moon is known as the “Hunter’s Moon” or the “Blood Moon,” its name came from a time when hunters would stalk the fields by Luna’s cold light in search of prey before the winter season began. Pick a place at sunset to watch it rise – a place having a stationary point with which you can gauge its progress. Make note of the time when the first rim appears and then watch how quickly it gains altitude! How long does it take before it rises above your marker?

On this night in 1749, the French astronomer Le Gentil was at the eyepiece of an 18? focal length telescope. His object of choice was the Andromeda Galaxy, which he believed to be a nebula. Little did he know at the time that his descriptive notes also included M32, a satellite galaxy of M31. It was the first small galaxy discovered, and it would be another 175 years before these were recognized as such by Edwin Hubble.

Even though it’s very bright tonight, take the time to view the Andromeda Galaxy for yourself. Located just about a degree west of Nu Andromeda, this ghost set against the starry night was known as far back as 905 AD, and was referred to as the “Little Cloud.” Located about 2.2 million light-years from our solar system, this expansive member of our Local Galaxy Group has delighted observers of all ages throughout the years. No matter if you view with just your eyes, a pair of binoculars or a large telescope, M31 still remains one of the most spectacular galaxies in the night.

Tuesday, October 30 – Tonight let’s have a look at the big, fat Moon as we return again with binoculars to identify the maria once again. Take the time to repeat the names to yourself and to study a map. One of the keys to successfully learning to identify craters is by starting with large, easily recognized features. Even though the Moon is very bright when full, try using colored or Moon filters with your telescope to have a look at the many surface features which throw amazing patterns across its surface. If you have none, a pair of sunglasses will suffice.

Look for things you might not ordinarily notice – such as the huge streak which emanates from crater Menelaus. Look at the pattern projected from Proclus – or the intense little dot of little-known Pytheas north of Copernicus. It’s hard to miss the blinding beacon of Aristarchus! Check the southeastern limb where the edge of Furnerius lights up the landscape…or how a nothing crater like Censorinus shines on the southeast shore of Tranquillitatis, while Dionysus echoes it on the southwest. Could you believe Manlius just north of central could be such a perfect ring – or that Anaxagoras would look like a northern polar cap? On the eastern limb we see the bright splash ray patterns surrounding ancient Furnerius – yet the rays themselves emanate from the much younger crater Furnerius A. All over the visible side, we see small points light up: a testament to the Moon’s violent past written in its scarred lines. Take a look now at the western limb…for the sunrise is about to advance around it.

Wednesday, October 31 – Happy Halloween! Many cultures around the world celebrate this day with a custom known as “Trick or Treat.” Tonight instead of tricking your little ghouls and goblins, why not treat them to a sweet view through your telescope or binoculars? What Halloween would be complete without a witch?! Easily found from a modestly dark site with the unaided eye, the Pleiades can be spotted well above the northeastern horizon within a couple of hours of nightfall. To average skies, many of the 7 bright components will resolve easily without the use of optical aid, but to telescopes and binoculars? M45 (Right Ascension: 03 : 47.0 – Declination: +24 : 07) is stunning…

First let’s explore a bit of history. The recognition of the Pleiades dates back to antiquity and its stars are known by many names in many cultures. The Greeks and Romans referred to them as the “Starry Seven,” the “Net of Stars,” “The Seven Virgins,” “The Daughters of Pleione,” and even “The Children of Atlas.” The Egyptians referred to them as “The Stars of Athyr,” the Germans as “Siebengestiren” (the Seven Stars), the Russians as “Baba” after Baba Yaga, the witch who flew through the skies on her fiery broom. The Japanese call them “Subaru,” Norsemen saw them as packs of dogs and the Tonganese as “Matarii” (the Little Eyes). American Indians viewed the Pleiades as seven maidens placed high upon a tower to protect them from the claws of giant bears, and even Tolkien immortalized the stargroup in “The Hobbit” as “Remmirath.” The Pleiades have even been mentioned in the Bible! So, you see, no matter where we look in our “starry” history, this cluster of seven bright stars has been part of it. But, let’s have some Halloween fun!

The date of the Pleiades culmination (its highest point in the sky) has been celebrated through its rich history by being marked with various festivals and ancient rites – but there is one particular rite that really fits this occasion! What could be more spooky on this date than to imagine a group of Druids celebrating the Pleiades’ midnight “high” with Black Sabbath? This night of “unholy revelry” is still observed in the modern world as “All Hallow’s Eve” or more commonly as Halloween. Although the actual date of the Pleiades midnight culmination is now on November 21 instead of October 31, why break with tradition? Thanks to its nebulous regions, M45 looks wonderfully like a “ghost” haunting the starry skies.

Treat yourself and your loved ones to the “scariest” object in the night. Binoculars give an incredible view of the entire region, revealing far more stars than are visible with the naked eye. Small telescopes at lowest power will enjoy M45?s rich, icy-blue stars and fog-like nebulosity. Larger telescopes and higher power reveal many pairs of double stars buried within its silver folds. No matter what you choose, the Pleiades definitely rock!

Thursday, November 1 – On this day in 1977, Charles Kowal made a wild discovery – Chiron. This represented the first discovery of a multitude of tiny, icy bodies that lie in the outer reaches of our solar system. Collectively known as Centaurs, they reside in unstable orbits between Jupiter and Neptune and are almost certainly “refugees”” from the Kuiper Belt.

Tonight let’s go for something small, but white-hot as we head for a dwarf star and planetary nebula, NGC 246. You’ll find it just a bit more than a fistwidth north-northeast of Beta Ceti (RA 00 47 03.34 Dec -11 52 18.9).

First discovered by Sir William Herschel and cataloged as object V.25, this 8th magnitude planetary nebula has a wonderful patchy, diffuse structure that envelops four stars. Around 1600 light-years away, the nebulosity you can see around the exterior edges was once the outer atmosphere of a star much like our own Sun. At the center of the nebula lies the responsible star – the fainter member of a binary system. While it is now in the process of becoming a white dwarf, we can still enjoy the product of this expanding shell of gas that is often called the “Skull Nebula.”

Friday, November 2 – Celestial scenery alert! If you’re up when the Moon rises, be sure to look for the close pairing of Jupiter and the Moon – they’re only about a fingerwidth apart! For a few viewers in the southernmost Africa region, this is an occultation event, so be sure to check resources for websites like IOTA which will give you times for locations in your area. What a great photographic opportunity… Clear skies!

Today celebrates the birth of an astronomy legend – Harlow Shapely. Born in 1885, the American-born Shapley paved the way in determining distances to stars, clusters, and the center of our Milky Way galaxy. Among his many achievements, Shapely was also the Harvard College Observatory director for many years. Today in 1917 also represents the night first light was seen through the Mt. Wilson 100? telescope.

Of course, Dr. Shapley spent his fair share of time on the Hooker telescope as well. One of his many points of study was globular clusters, their distance, and their relationship to the halo structure of our galaxy. Tonight let’s have a look at a very unusual little globular located about a fistwidth south-southeast of Beta Ceti and just a couple of degrees north-northwest of Alpha Sculptor (RA 00:52:47.5 Dec -26:35:24), as we have a look at NGC 288.

Discovered by William Herschel on October 27, 1785, and cataloged by him as H VI.20, the class X globular cluster blew apart scientific thinking in the late 1980?s as a study of perimeter globulars showed it to be more than 3 million years older than similar globulars – thanks to the color magnitude diagrams of Hertzsprung and Russell. By identifying both its blue and red branches, it was shown that many of NGC 288?s stars are being stripped away by tidal forces and contributing to the formation of the Milky Way’s halo structure. In 1997, three additional variable stars were discovered in this cluster.

At magnitude 8, this small globular is easy for southern observers, but faint for northern ones. If you are using binoculars, be sure to look for the equally bright spiral galaxy NGC 253 to the globular’s north.

Saturday, November 3 – On this day in 1955, one of the few documented cases of a person being hit by a meteorite occurred. What are the odds on that? In 1957 the Russian space program launched its first “live” astronaut into space – Laika. Carried on board Sputnik 2, our canine hero was the first living creature to reach orbit. The speedily developed Sputnik 2 was designed with sensors to transmit the ambient pressure, breathing patterns and heartbeat of its passenger, and also had a television camera on board to monitor its occupant. The craft also studied ultraviolet and x-ray radiation to further assess the impact of space flight upon live occupants. Unfortunately, the technology of the time offered no way to return Laika to Earth, so she perished in space. On April 14, 1958, Laika and Sputnik 2 returned to Earth in a fiery re-entry after 2,570 orbits.

Since we’ve got the scope out, let’s go have another look at that galaxy we spied last night!

Discovered by Caroline Herschel on September 23, 1783, NGC 253 (RA 00 47.6 Dec -25 17) is the brightest member of a concentration of galaxies known as the Sculptor Group, near to our own local group and the brightest of all outside it. Cataloged as both H V.1 and Bennett 4, this 7th magnitude beauty is also known as Caldwell 65, and due to both its brightness and oblique angle is often called the “Silver Dollar Galaxy.” As part of the SAC 110 best NGCs, you can even spot this one if you don’t live in the Southern Hemisphere. At around 10 million light-years away, this very dusty, star-forming Seyfert galaxy rocks in even a modest telescope!

Sunday, November 4 – This morning will be the peak of the Southern Taurid meteor shower. Already making headlines around the world for producing fireballs, the Taurids will be best visible in the early morning hours, but the Moon will interfere. The radiant for this shower is, of course, the constellation of Taurus and red giant Aldeberan, but did you know the Taurids are divided into two streams?

It is surmised that the original parent comet shattered as it passed our Sun around 20,000 to 30,000 years ago. The larger “chunk” continued orbiting and is known as periodic comet Encke. The remaining debris field turned into smaller asteroids, meteors and larger fragments that often pass through our atmosphere creating the astounding “fireballs” known as bolides. Although the fall rate for this particular shower is rather low at 7 per hour, these slow traveling meteors (27 km or 17 miles per second) are usually very bright and appear to almost “trundle” across the sky. With the chances high all week of seeing a bolide, this makes a bit of quiet contemplation under the stars worthy of a morning walk. Be sure to look at how close Saturn is to the Moon!

For unaided eye or binocular observers – or those who just wish something a bit “different” tonight – have a look at 19 Pisces. You’ll find it as the easternmost star in the small “circlet” just south of the Great Square of Pegasus.

Also known as TX, you’ll find this one quite delightful for its strong red color. TX is a cool giant star which varies slightly in magnitude on an irregular basis. This carbon star is located anywhere from 400 to 1000 light-years away and rivals even R Leporis’ crimson beauty.

Until next week? Wishing you clear skies!