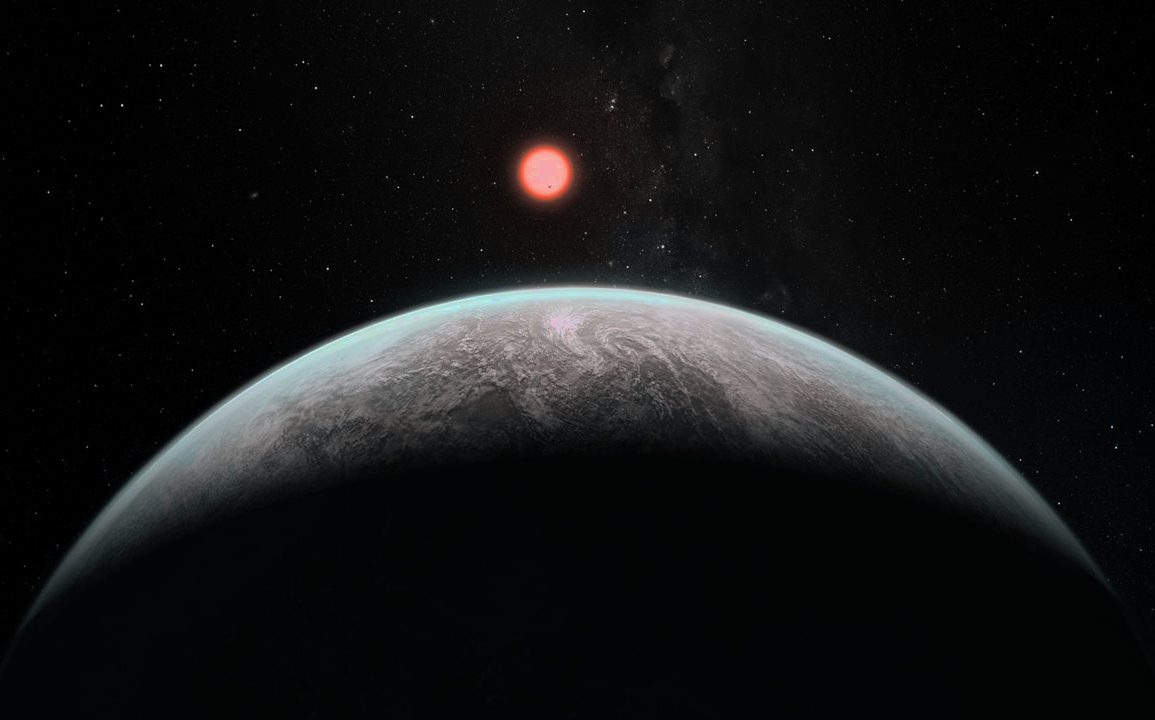

After a few decades of simply finding exoplanets, humanity is starting to be able to do something more – peer into their atmospheres. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has already started looking at the atmospheres of some larger exoplanets around brighter stars. But in many cases, scientists are still developing models that both explain what the planet’s atmosphere is made of and match the data. A new study from researchers at UC Riverside, NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center, American University, and the University of Maryland looks at what one particular atmospheric process might look like on an exoplanet – volcanism.

Continue reading “Could We Directly Observe Volcanoes on an Exoplanet?”Watch an Actual Exoplanet Orbit its Star for 17 Years

Searching for exoplanets is incredibly difficult given their literal astronomical distances from Earth, which is why a myriad of methods have been created to find them. These include transit, redial velocity, astrometry, gravitational microlensing, and direct imaging. It is this last method that was used to recently create a time-lapse video that compresses a mind-blowing 17 years of the partial orbit of exoplanet, Beta Pictoris b, into 10 seconds. The data to create the video was collected between 2003 and 2020, it encompasses approximately 75 percent of the total orbit, and marks the longest time-lapse video of an exoplanet ever produced.

Continue reading “Watch an Actual Exoplanet Orbit its Star for 17 Years”A Fleet of Space Telescopes Flying in Formation Could Reveal Details on Exoplanets

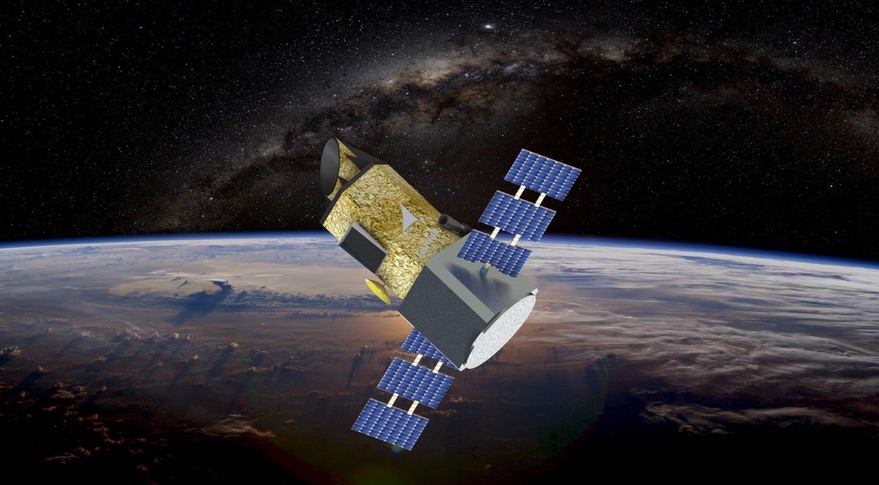

We’ve found thousands of exoplanets in the last couple of decades. We’ve discovered exoplanets unlike anything in our own Solar System. But even with all we’ve found, it seems like there’s more and more to discover. Space scientists of all types are always working on the next generation of missions, which is certainly true for exoplanets.

Chinese researchers are developing an idea for an exoplanet-detecting array of space telescopes that acts as an interferometer. But it won’t only detect them. The array will use direct imaging to characterize distant exoplanets in more detail.

Continue reading “A Fleet of Space Telescopes Flying in Formation Could Reveal Details on Exoplanets”A Technique to Find Oceans on Other Worlds

You could say that the study of extrasolar planets is in a phase of transition of late. To date, 4,525 exoplanets have been confirmed in 3,357 systems, with another 7,761 candidates awaiting confirmation. As a result, exoplanet studies have been moving away from the discovery process and towards characterization, where follow-up observations of exoplanets are conducted to learn more about their atmospheres and environments.

In the process, exoplanet researchers hope to see if any of these planets possess the necessary ingredients for life as we know it. Recently, a pair of researchers from Northern Arizona University, with support from the NASA Astrobiology Institute’s Virtual Planetary Laboratory (VPL), developed a technique for finding oceans on exoplanets. The ability to find water on other planets, a key ingredient in life on Earth, will go a long way towards finding extraterrestrial life.

Continue reading “A Technique to Find Oceans on Other Worlds”Fomalhaut’s Planet Has Gone Missing, But it Might Have Been Something Even More Interesting

Planets don’t simply disappear. And yet, that appears to be what happened to Fomalhaut b (aka. Dagon), an exoplanet candidate located 25 light-years from Earth. Observed for the first time by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2004, then confirmed by follow-up observations in 2008 and 2012, this exoplanet candidate was the first to be detected in visible wavelengths (i.e. the Direct Imaging Method.)

Over time, this candidate got fainter and wider until it disappeared from sight altogether. This led to all kinds of speculation, which included the possibility of a collision that reduced the planet to debris. Recently, a team of astronomers from the University of Arizona has suggested another possibility – Fomalhaut b was never a planet at all, but an expanding cloud of dust from two planetesimals that smashed together.

Continue reading “Fomalhaut’s Planet Has Gone Missing, But it Might Have Been Something Even More Interesting”Earth is an Exoplanet to Aliens. This is What They’d See

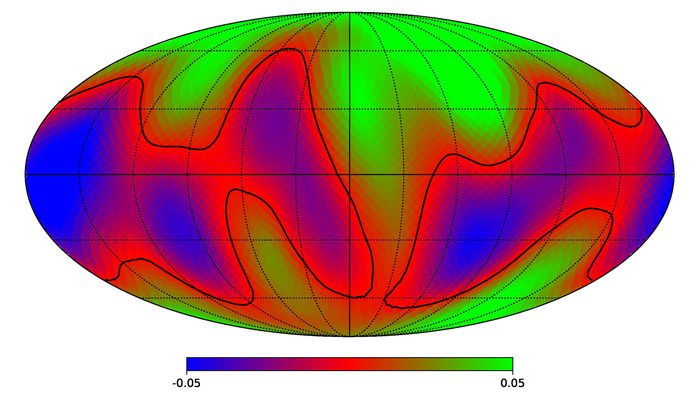

The study of exoplanets has matured considerably in the last ten years. During this time, the majority of the over 4000 exoplanets that are currently known to us were discovered. It was also during this time that the process has started to shift from the process of discovery to characterization. What’s more, next-generation instruments will allow for studies that will reveal a great deal about the surfaces and atmospheres of exoplanets.

This naturally raises the question: what would a sufficiently-advanced species see if they were studying our planet? Using multi-wavelength data of Earth, a team of Caltech scientists was able to construct a map of what Earth would look like to distant alien observers. Aside from addressing the itch of curiosity, this study could also help astronomers reconstruct the surface features of “Earth-like” exoplanets in the future.

Continue reading “Earth is an Exoplanet to Aliens. This is What They’d See”Direct Observations of a Planet Orbiting a Star 63 Light-Years Away

In the past thirty years, the number of planets discovered beyond our Solar System has grown exponentially. Unfortunately, due to the limitations of our technology, the vast majority of these exoplanets have been discovered by indirect means, often by detecting the transits of planets in front of their stars (the Transit Method) or by the gravitational influence they exert on their star (the Radial Velocity Method).

Very few have been imaged directly, where the planets have been observed in visible light or infrared wavelengths. One such planet is Beta Pictoris b, a young massive exoplanet that was first observed in 2008 by a team from the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Recently, the same team tracked this planet as it orbited its star, resulting in some stunning images and an equally impressive time-lapse video.

Continue reading “Direct Observations of a Planet Orbiting a Star 63 Light-Years Away”

How the Next Generation of Ground-Based Super-Telescopes will Directly Observe Exoplanets

Over the past few decades, the number of extra-solar planets that have been detected and confirmed has grown exponentially. At present, the existence of 3,778 exoplanets have been confirmed in 2,818 planetary systems, with an additional 2,737 candidates awaiting confirmation. With this volume of planets available for study, the focus of exoplanet research has started to shift from detection towards characterization.

Continue reading “How the Next Generation of Ground-Based Super-Telescopes will Directly Observe Exoplanets”

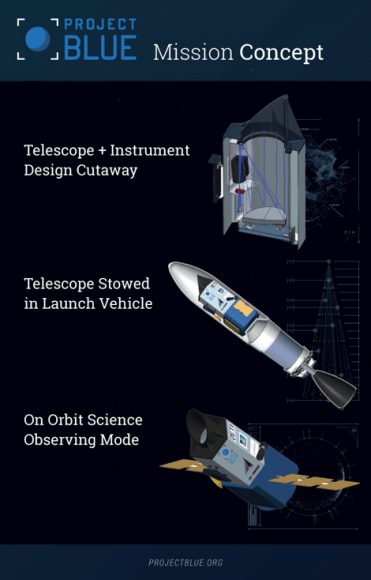

Project Blue: Building a Space Telescope that Could Directly Observe Planets Around Alpha Centauri

In the past few decades, thousands of exoplanets have been discovered in neighboring star systems. In fact, as of October 1st, 2017, some 3,671 exoplanets have been confirmed in 2,751 systems, with 616 systems having more than one planet. Unfortunately, the vast majority of these have been detected using indirect means, ranging from Gravitational Microlensing to Transit Photometry and the Radial Velocity Method.

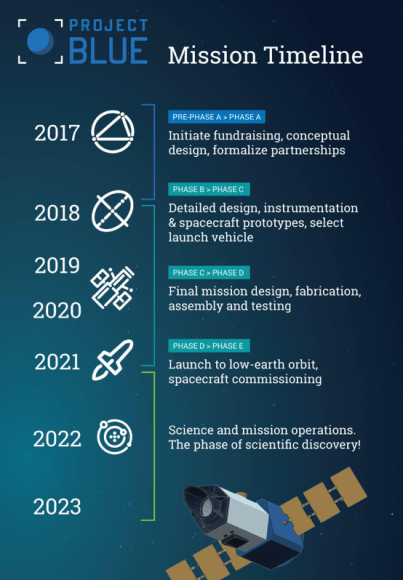

What’s more, we have been unable to study these planets up close because the necessary instruments do not yet exist. Project Blue, a consortium of scientists, universities and institutions, is looking to change that. Recently, they launched a crowdfunding campaign through Indiegogo to finance the development of a space telescope that will start looking for exoplanets in the Alpha Centauri system by 2021.

In addition to its commercial and academic partners, Project Blue is a collaborative effort between the BoldlyGo Institute, Mission Centaur, the SETI Institute, and the University of Massachusetts Lowell. It is steered by a Science & Technology Advisory Committee (STAC) composed of science and technology experts who are dedicated to space exploration and the search for life in our Universe.

To accomplish their goal of directly studying exoplanets, Project Blue is seeking to leverage recent changes in space exploration, which include improved instruments and methodology, the rate at which exoplanet have been discovered in recent years, and increased collaboration between the private and public sector. As SETI Institute President and CEO Bill Diamond explained in a recent SETI press statement:

“Project Blue builds on recent research in seeking to show that Earth is not alone in the cosmos as a planet capable of supporting life, and wouldn’t it be amazing to see such a planet in our nearest neighboring star system? This is the fundamental reason we search.”

As noted, virtually all exoplanet discoveries that have been made in the past few decades were done using indirect methods – the most popular of which is Transit Photometery. This method is what the Kepler and K2 missions relied on to detect a total of 5,017 exoplanet candidates and confirm the existence of 2,470 exoplanets (30 of which were found to orbit within their star’s habitable zone).

This method consists of astronomers monitoring distant stars for periodic dips in brightness, which are caused by a planet transiting in front of the star. By measuring these dips, scientists are able to determine the size of planets in that system. Another popular technique is the Radial Velocity (or Doppler) Method, which measures changes in a star’s position relative to the observer to determine how massive its system of planets are.

These and other methods (alone or in combination) have allowed for the many discoveries that have been made to take place. But so far, no exoplanets have been directly imaged, which is due to the cancelling effect stars have on optical instruments. Basically, astronomers have been unable to spot the light being reflected off of an exoplanet’s atmosphere because the light coming from the star is up to ten billion times brighter.

The challenge has thus become how to go about blocking this light so that the planets themselves can become visible. One proposed solution to this problem is NASA’s Starshade concept, a giant space structure that would be deployed into orbit alongside a space telescope (most likely, the James Webb Space Telescope). Once in orbit, this structure would deploy its flower-shaped foils to block the glare of distant stars, thus allowing the JWST and other instruments to image exoplanets directly.

But since Alpha Centauri is a binary system (or trinary, if you count Proxima Centauri), being able to directly image any planets around them is even more complicated. To address this, Project Blue has developed plans for a telescope that will be able to suppress light from both Alpha Centauri A and B, while simultaneously taking images of any planets that orbit them. It’s specialized starlight suppression system consists of three components.

First, there is the coronagraph, an instrument which will rely on multiple techniques to block starlight. Second, there’s the deformable mirror, low-order wavefront sensors, and software control algorithms that will manipulate incoming light. Last, there is the post-processing method known as Orbital Differntial Imaging (ODI), which will allow the Project Blue scientist to enhance the contrast of the images taken.

Given its proximity to Earth, the Alpha Centauri system is the natural choice for conducting such a project. Back in 2012, an exoplanet candidate – Alpha Centauri Bb – was announced. However, in 2015, further analysis indicated that the signal detected was an artefact in the data. In March of 2015, a second possible exoplanet (Alpha Centauri Bc) was announced, but its existence has also come to be questioned.

With an instrument capable of directly imaging this system, the existence of any exoplanets could finally be confirmed (or ruled out). As Franck Marchis – the Senior Planetary Astronomer at the SETI Institute and Project Blue Science Operation Lead – said of the Project:

“Project Blue is an ambitious space mission, designed to answer to a fundamental question, but surprisingly the technology to collect an image of a “Pale Blue Dot” around Alpha Centauri stars is there. The technology that we will use to reach to detect a planet 1 to 10 billion times fainter than its star has been tested extensively in lab, and we are now ready to design a space-telescope with this instrument.”

If Project Blue meets its crowdfunding goals, the organization intends to deploy the telescope into Near-Earth Orbit (NEO) by 2021. The telescope will then spend the next two years observing the Alpha Centauri system with its corongraphic camera. All told, between the development of the instrument and the end of its observation campaign, the mission will last six years, a relatively short run for an astronomical mission.

However, the potential payoff for this mission would be incredibly profound. By directly imaging another planet in the closest star system to our own, Project Blue could gather vital data that would indicate if any planets there are habitable. For years, astronomers have attempted to learn more about the potential habitability of exoplanets by examining the spectral data produced by light passing through their atmospheres.

However, this process has been limited to massive gas giants that orbit close to their parent stars (i.e. “Super-Jupiters”). While various models have been proposed to place constraints on the atmospheres of rocky planets that orbit within a star’s habitable zone, none have been studied directly. Therefore, if it should prove to be successful, Project Blue would allow for some of the greatest scientific finds in history.

What’s more, it would provide information that could a long way towards informing a future mission to Alpha Centauri, such as Breakthrough Starshot. This proposed mission calls for the use of a large laser array to propel a lightsail-driven nanocraft up to relativistic speeds (20% the speed of light). At this rate, the craft would reach Alpha Centauri within 20 years time and be able to transmit data back using a series of tiny cameras, sensors and antennae.

As the name would suggest, Project Blue hopes to capture the first images of a “Pale Blue Dot” that orbits another star. This is a reference to the photograph of Earth that was taken by the Voyager 1 probe on February 19th, 1990, after the probe concluded its primary mission and was getting ready to leave the Solar System. The photos were taken at the request of famed astronomer and science communicator Carl Sagan.

When looking at the photographs, Sagan famously said: “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.” Thereafter, the name “Pale Blue Dot” came to be synonymous with Earth and capture the sense of awe and wonder that the Voyage 1 photographs evoked.

More recently, other “Pale Blue Dot” photographs have been snapped by missions like the Cassini orbiter. While photographing Saturn and its system of rings in the summer of 2013, Cassini managed to capture images that showed Earth in the background. Given the distance, Earth once again appeared as a small point of light against the darkness of space.

Beyond relying on crowdfunding and the participation of multiple non-profit organizations, this low-cost mission also seeks to capitalize on a growing trend in space exploration, – which is open participation and collaborations between scientific institutions and citizen scientists. This is one of the primary purposes behind Project Blue, which is to engage the public and educate them about the importance of space exploration.

As Jon Morse, the CEO of the BoldlyGo Institute, explained:

“The future of space exploration holds boundless potential for answering profound questions about our existence and destiny. Space-based science is a cornerstone for investigating such questions. Project Blue seeks to engage a global community in a mission to search for habitable planets and life beyond Earth.”

As of the penning of this article, Project Blue has managed to raise $125,561 USD of their goal of $175,000. For those interesting in backing this project, Project Blue’s Indiegogo campaign will remain open for another 11 days. And be sure to check out their promotional video as well:

Further Reading: SETI, Project Blue, Indiegogo

Prying Planets Out of The Shadows: The Gemini Planet Imager’s First Year of Light

This year marks the 20th anniversary of 51 Peg b, the first exoplanet detected around a Sun-like star. And although the number of sheer detections in the years since have been remarkable, it’s also remarkable how little we still know about these alien worlds, save for their distances from their host stars, their radii, and sometimes their masses.

But the ability to directly image these worlds provides the opportunity to change all that. “It’s the tip of the iceberg,” said Marshall Perrin from the Space Telescope Science Institute in a press conference at the American Astronomical Society’s meeting earlier today. “In the long run, we think that imaging offers perhaps the best path to characterizing rocky planets on Earth-like orbits.”

Perrin highlighted two intriguing results from the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI), an instrument designed not only to resolve the dim light of an exoplanet, but also analyze a planet’s atmospheric temperature and composition.

HR 8799

The first system observed with GPI was the well-known HR 8799 system, a large star orbited by four planets, located 130 light-years away. Previously, the Keck telescope had measured the atmosphere of one of the planets, HR 8799c, in six hours of observing time. But GPI matched that in only a half hour of telescope time and in less-than-ideal weather too. So the team quickly turned to the planet’s twin, HR 8799d.

“What we found really surprised us,” said Perrin. “These two planets have been known to have the same brightness and the same broadband colors. But looking at their spectra, they’re surprisingly different.”

Perrin and his colleagues think the likely culprit is clouds. It’s possible that one planet has a uniform cloud cover, whereas the other planet has a more patchy cloud cover, allowing astronomers to see deeper into the atmosphere. Perrin, however, cautions that this explanation is still under interpretation.

“The fact that GPI was able to extract new knowledge from these planets on the first commissioning run in such a short amount of time, and in conditions that it was not even designed to work, is a real testament to how revolutionary GPI will be to the field of exoplanets,” said GPI team member Patrick Ingraham from Stanford University in a news release.

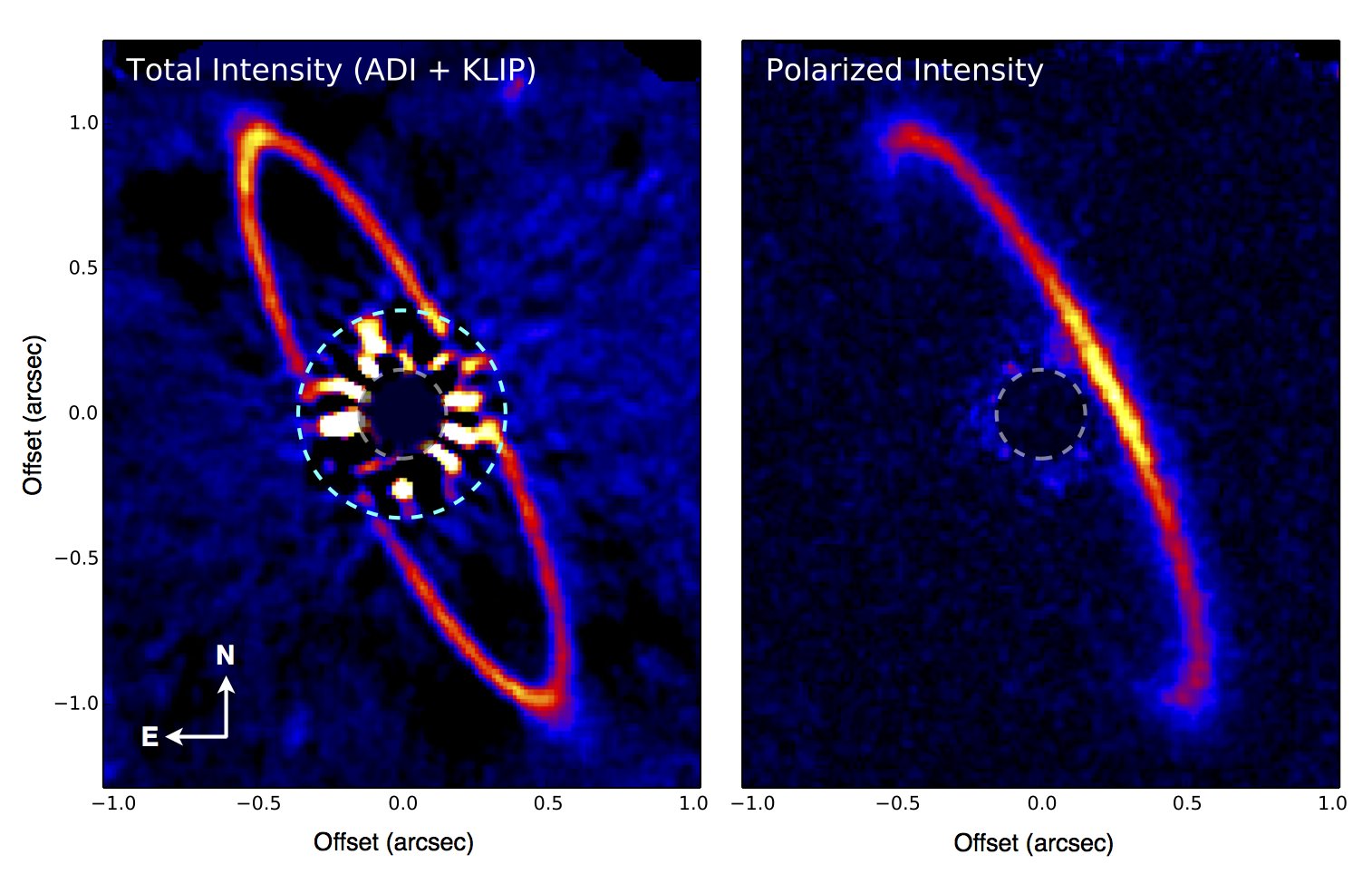

HR 4796A

Perrin’s presentation also introduced never-seen details in the dusty ring around the young star HR 4796A. GPI also has the unique ability of detecting only polarized light, which sheds light on different physical properties.

Although the details are fairly technical, “the short version is that reconciling the patterns we see in polarized intensity and in total intensity has forced us to think of this not as a very diffuse disk but one that is actually dense enough to partially opaque,” said Perrin.

The disk may be roughly analogous to one of Saturn’s rings.

“GPI now is moving into an exciting phase of full operations,” said Perrin, concluding his talk. “We’ll be opening up a lot of new discoveries hopefully over the next few years. And in the long run taking these technologies and scaling them to future 30-meter telescopes, and perhaps large telescopes in space, to continue direct imaging and push down toward the Earth-like planet regime.”