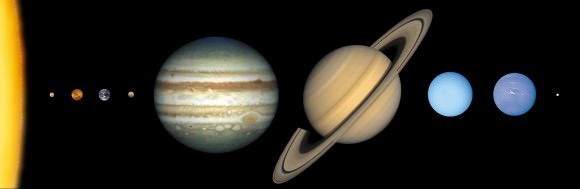

If you’re interested in planets, the good news is there’s plenty of variety to choose from in our own Solar System. From the ringed beauty of Saturn, to the massive hulk of Jupiter, to the lead-melting temperatures on Venus, each planet in our solar system is unique — with its own environment and own story to tell about the history of our Solar System.

What also is amazing is the sheer size difference of planets. While humans think of Earth as a large planet, in reality it is dwarfed by the massive gas giants lurking at the outer edges of our Solar System. This article explores the planets in order of size, with a bit of context as to how they got that way.

A Short History of the Solar System:

No human was around 4.5 billion years ago when the Solar System was formed, so what we know about its birth comes from several sources: examining rocks on Earth and other places, looking at other solar systems in formation and doing computer models, among other methods. As more information comes in, some of our theories of the Solar System must change to suit the new evidence.

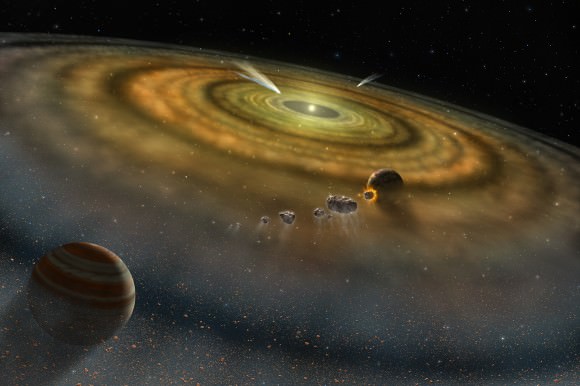

Today, scientists believe the Solar System began with a spinning gas and dust cloud. Gravitational attraction at its center eventually collapsed to form the Sun. Some theories say that the young Sun’s energy began pushing the lighter particles of gas away, while larger, more solid particles such as dust remained closer in.

Over millions and millions of years, the gas and dust particles became attracted to each other by their mutual gravities and began to combine or crash. As larger balls of matter formed, they swept the smaller particles away and eventually cleared their orbits. That led to the birth of Earth and the other eight planets in our Solar System. Since much of the gas ended up in the outer parts of the system, this may explain why there are gas giants — although this presumption may not be true for other solar systems discovered in the universe.

Until the 1990s, scientists only knew of planets in our own Solar System and at that point accepted there were nine planets. As telescope technology improved, however, two things happened. Scientists discovered exoplanets, or planets that are outside of our solar system. This began with finding massive planets many times larger than Jupiter, and then eventually finding planets that are rocky — even a few that are close to Earth’s size itself.

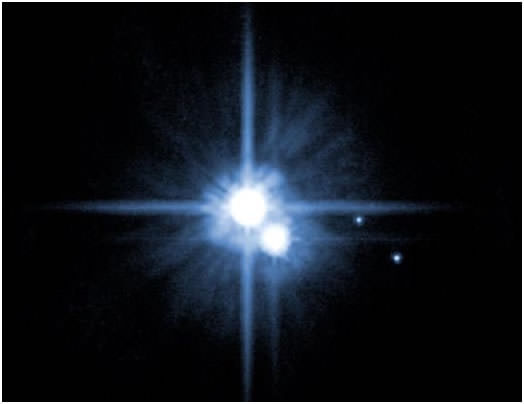

The other change was finding worlds similar to Pluto, then considered the Solar System’s furthest planet, far out in our own Solar System. At first astronomers began treating these new worlds like planets, but as more information came in, the International Astronomical Union held a meeting to better figure out the definition.

The result was redefining Pluto and worlds like it as a dwarf planet. This is the current IAU planet definition:

“A celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.”

Size of the Eight Planets:

According to NASA, this is the estimated radii of the eight planets in our solar system, in order of size. We also have included the radii sizes relative to Earth to help you picture them better.

- Jupiter (69,911 km / 43,441 miles) – 1,120% the size of Earth

- Saturn (58,232 km / 36,184 miles) – 945% the size of Earth

- Uranus (25,362 km / 15,759 miles) – 400% the size of Earth

- Neptune (24,622 km / 15,299 miles) – 388% the size of Earth

- Earth (6,371 km / 3,959 miles)

- Venus (6,052 km / 3,761 miles) – 95% the size of Earth

- Mars (3,390 km / 2,460 miles) – 53% the size of Earth

- Mercury (2,440 km / 1,516 miles) – 38% the size of Earth

Jupiter is the behemoth of the Solar System and is believed to be responsible for influencing the path of smaller objects that drift by its massive bulk. Sometimes it will send comets or asteroids into the inner solar system, and sometimes it will divert those away.

Saturn, most famous for its rings, also hosts dozens of moons — including Titan, which has its own atmosphere. Joining it in the outer solar system are Uranus and Neptune, which both have atmospheres of hydrogen, helium and methane. Uranus also rotates opposite to other planets in the solar system.

The inner planets include Venus (once considered Earth’s twin, at least until its hot surface was discovered); Mars (a planet where liquid water could have flowed in the past); Mercury (which despite being close to the sun, has ice at its poles) and Earth, the only planet known so far to have life.

To learn more about the Solar System, check out these resources:

Planets (NASA)

Solar System (USGS)

Exploring the Planets (National Air and Space Museum)

Windows to the Universe (National Earth Science Teachers Association)

Solar System (National Geographic, requires free registration)

Our solar system does NOT have only eight planets, and by posting only the IAU planet definition, you are telling only one side in an ongoing debate. Pluto and the small worlds similar to it ARE planets according to the equally legitimate geophysical planet definition, as articulated by New Horizons Principal Investigator Dr. Alan Stern. The geophysical definition defines planets as any celestial non-self-luminous spheroidal bodies in orbit around a star or free-floating in space. In other words, if a world is large enough to be shaped by its own gravity, which squeezes it into a spherical or nearly spherical shape, it is a planet. Pluto and the dwarf planets have the same processes and structures as the larger planets; the only difference is that they are smaller.

The IAU meeting and decision should not be referred to as some sort of gospel truth. Only four percent of the IAU even voted on it, and most are not planetary scientists. The vote was conducted in violation of the IAU’s own bylaws, because a last-minute resolution was put to the floor of the General Assembly without first being vetted by the proper IAU committee, as required. Hundreds of planetary scientists immediately rejected the definition in a formal petition led by Stern. Ironically, Stern is the person who first coined the term “dwarf planet,” but he intended it to refer to a new subclass of planets in addition to terrestrials and jovians, not to refer to non-planets. The four percent of the IAU who voted on this misused his term. The geophysical planet definition includes dwarf planets as a subclass of the broader category of planets.

Also, your graphic of TNOs is outdated. Eris is not larger than Pluto. It was originally thought to be so, but in November 2010, a team of astronomers led by Dr. Bruno Sicardy observed Eris occult a star and found it to be marginally smaller than Pluto though 27 percent more massive. More massive means more rocky and therefore more planet-like (Pluto is estimated to be 70 percent rock).

Apologies, I’ve replaced with a picture of Pluto instead.

Yes, let’s get with the program, please? Bruno Sicardy’s paper was published long enough ago that Ms. Howell should’ve had plenty of time to incorporate the lastest numbers on Pluto and Eris. That graphic with Eris larger than Pluto is way old. Let’s try to replace it, okay? Pluto is at least 22 kilometers/13 miles greater in diameter than Eris.

Regarding the 2006 new definition of a planet, why are dwarf stars like our sun considered stars, but dwarf planets are not a subcategory (as intended by Alan Stern) of planets? The same is true of dwarf galaxies, too.

It is obviously more political than scientific. I know of one IAU member who was threatened with the destruction of his astronomical career if he voted to keep Pluto a planet. Another member wanted to recast his vote once he realized the true import of the rancid, ramrodded resolution. The August 2015 IAU General Assembly in Honolulu should address this fiasco and replanetize Ceres and Pluto, and make planets of all duly-accepted dwarf planets, viz., Makemake, Haumea, and Eris — and even Charon!

The NASA web page I took the graphic from was updated in 2012, but I see now that there is a problem. I’ve removed the TNO picture and replaced with a picture of Pluto. Thanks.

Here is an article about Pluto being bigger than Eris.

http://news.sciencemag.org/space/2014/03/scienceshot-pluto-regains-its-title-largest-object-its-neighborhood

Thanks, Ms. Howell! You rock at least 70%!!!!!!!

Sorry about my earlier tone, Ms. Howell. You’re okay in my book. Peace.

Interesting. Pluto is 213.24 yards short of the distance of a marathon longer in diameter than Eris, using Sicardy’s data. 26 miles and 171.76 yards. Maybe Pheidippides wouldn’t have dropped dead if that’s all he’d had to run…..