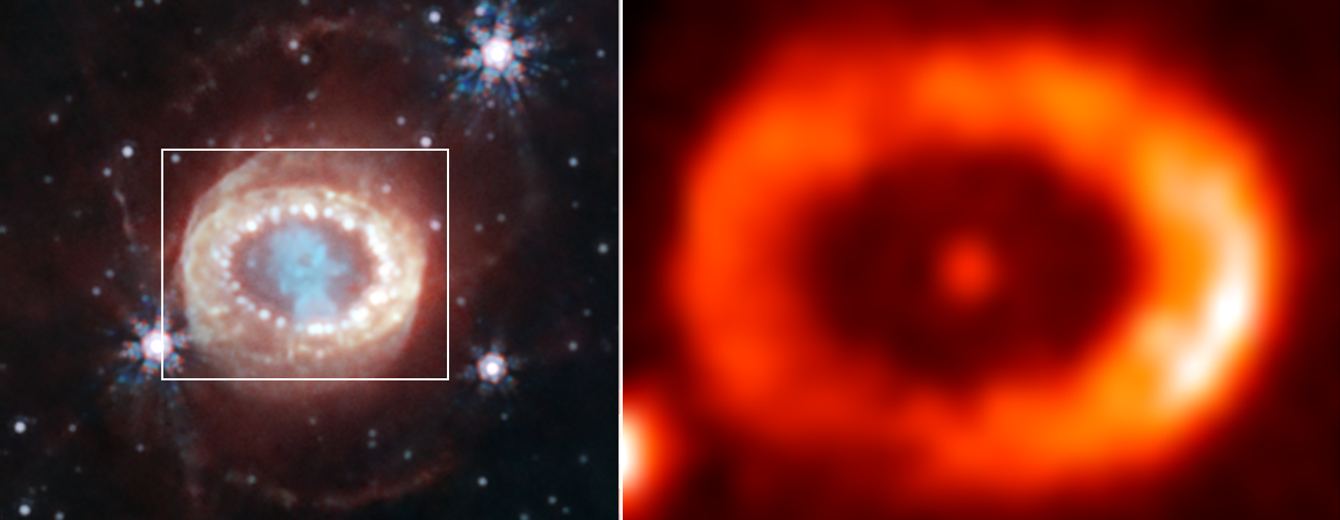

I can remember seeing images of SN1987A as it developed back in 1987. It was the explosion of a star, a supernova in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Over the decades that followed, it was closely monitored in particular the expanding debris cloud. Predictions suggested there may be a neutron star or even a black hole at the core but the resolution of the telescopes was insufficient to pick anything up. Now we have the James Webb Space Telescope and using its more powerful technology, signs of a neutron star have been detected.

Continue reading “Finally! Webb Finds a Neutron Star from Supernova 1987A”A new Hubble Image Reveals a Shredded Star in a Nearby Galaxy

The Hubble Space Telescope, to which we owe our current estimates for the age of the universe and the first detection of organic matter on an exoplanet, is very much doing science and still alive. It’s latest masterpiece remixes an old hit – apparently a growing trend in space science as well as space music.

Continue reading “A new Hubble Image Reveals a Shredded Star in a Nearby Galaxy”Astronomers Watch a Star Die and Then Explode as a Supernova

It’s another first for astronomy.

For the first time, a team of astronomers have imaged in real-time as a red supergiant star reached the end of its life. They watched as the star convulsed in its death throes before finally exploding as a supernova.

And their observations contradict previous thinking into how red supergiants behave before they blow up.

Continue reading “Astronomers Watch a Star Die and Then Explode as a Supernova”We’re in the Milky Way’s Second Life. Star Formation was Shut Down for Billions of Years

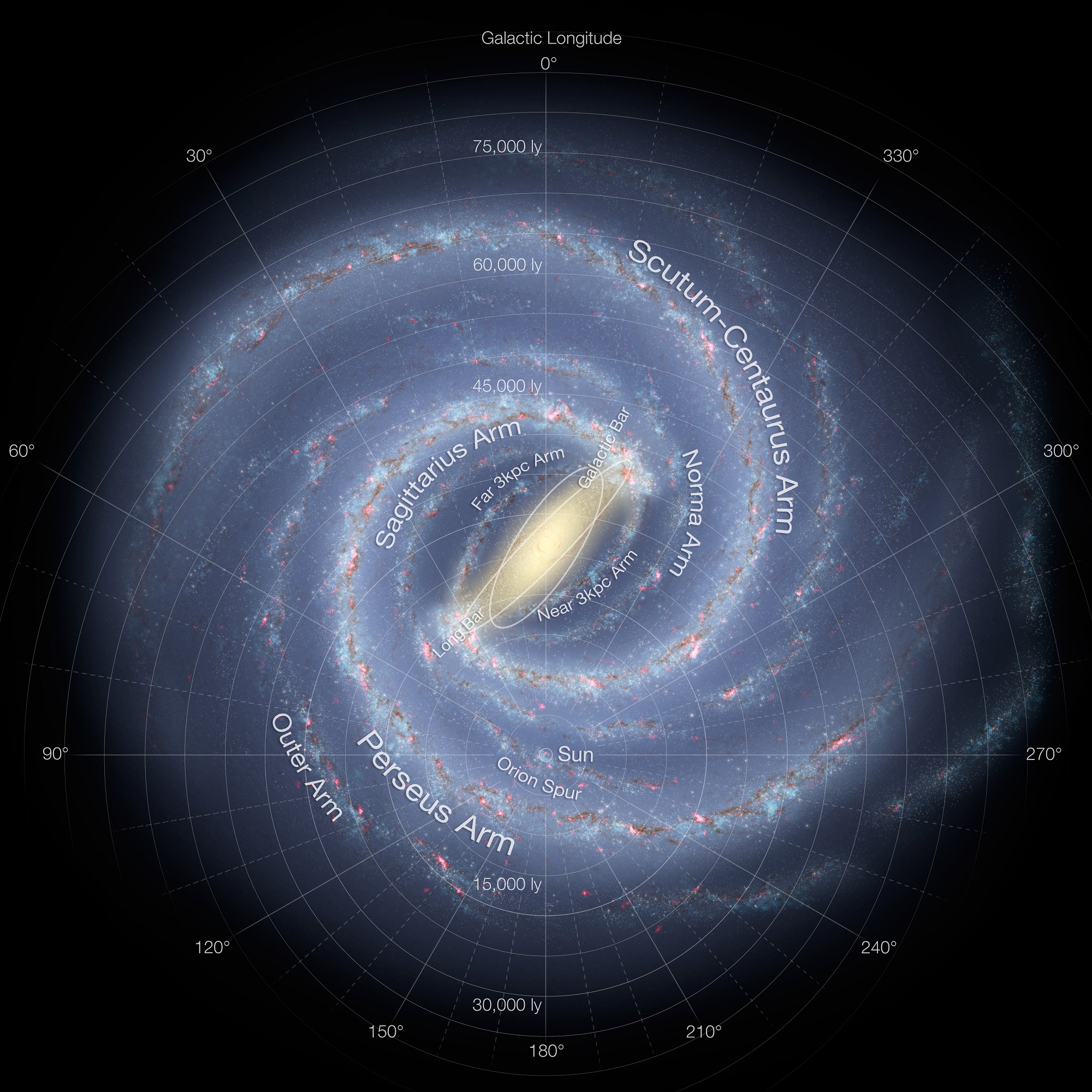

Since the birth of modern astronomy, scientists have sought to determine the full extent of the Milky Way galaxy and learn more about its structure, formation and evolution. According to current theories, it is widely believed that the Milky Way formed shortly after the Big Bang (roughly 13.51 billion years ago). This was the result of the first stars and star clusters coming together, as well as the accretion of gas directly from the Galactic halo.

For the First Time, Astronomers Have Found a Star That Survived its Companion Exploding as Supernova

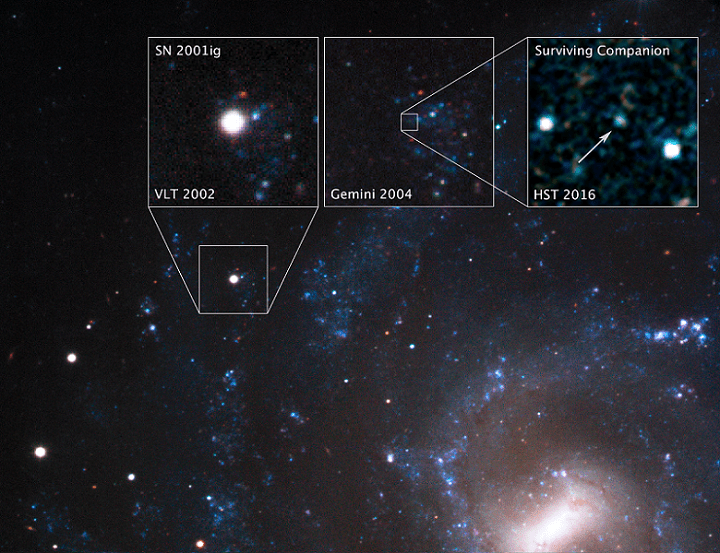

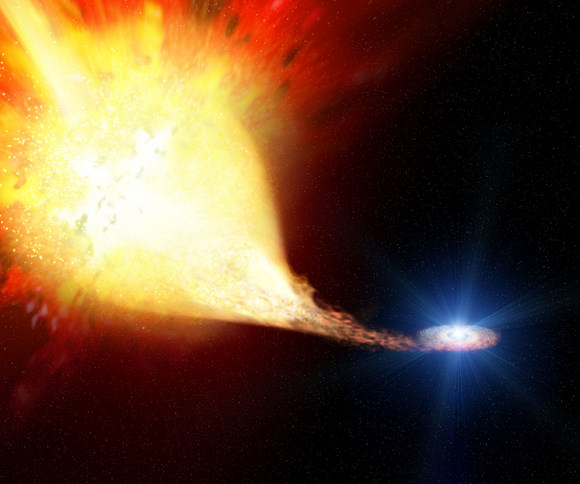

A Type II supernova is a truly amazing astronomical event. As with all supernovae, a Type II consists of a star experiencing core collapse at the end of its life cycle and exploding, causing it to shed its outer layers. A subclass of this type is known as Type IIb, which are stars that have been stripped of their hydrogen fuel and undergo collapse because they are no longer able to maintain fusion in their core.

Seventeen years ago, astronomers were fortunate enough to witness a Type IIb supernova in the galaxy NGC 7424, located 40 million light-years away in the southern constellation Grus. Now that this supernova has faded, the Hubble Space Telescope recently captured the first image of a surviving companion, thus demonstrating that supernovae do indeed happen in double-star systems.

The study, titled “Ultraviolet Detection of the Binary Companion to the Type IIb SN 2001ig“, was recently published in the Astrophysical Journal. The study was led by Stuart Ryder of the Australian Astronomical Observatory and included members from California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the Space Telescope Science Institute (STSI), the University of Amsterdam, the University of Arizona, the University of York, and the University of California.

This discovery is the most compelling evidence to date that some supernovae originate as a result of siphoning between binary pairs. As Stuart Ryder indicated in a recent NASA press release:

“We know that the majority of massive stars are in binary pairs. Many of these binary pairs will interact and transfer gas from one star to the other when their orbits bring them close together.”

The supernova, called SN 2001ig, was pinpointed by astronomers in 2002 using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). In 2004, these observations were followed-up with the Gemini South Observatory, which first hinted at the presence of a surviving binary companion. Knowing the exact coordinates, Ryder and his team were able to focus Hubble on that location as the supernova’s glow faded.

The find was especially fortuitous because it might also shed light on a astronomical mystery, which is how stripped-envelop supernovae lose their outer envelopes. Originally, scientists believed they were the result of stars with very fast winds that pushed off their outer envelopes. However, when astronomers began looking for the primary stars which spawned these supernovae, they could not find them.

As Ori Fox, a member of the Space Telescope Science Institute and a co-author on the paper, explained:

“That was especially bizarre, because astronomers expected that they would be the most massive and the brightest progenitor stars. Also, the sheer number of stripped-envelope supernovas is greater than predicted.”

This led scientists to theorize that many of the stripped-envelop stars were the primary in lower-mass binary star systems. All that remained was to find a supernova that was part of a binary system, which Ryder and his colleagues set out to do. This was no easy task, seeing as how the companion was rather faint and at the very limits of what Hubble could see.

In addition, not many supernovae are known to go off within this distance range. Last, but not least, they had to know the exact position through very precise measurements. Thanks to Hubble’s exquisite resolution and ultraviolet capability, they were able to find and photograph the surviving companion.

Prior to the supernova, the stars orbited each other with a period of about one year. When the primary star exploded, it had an impact on the companion, but it remained intact. Because of this, SN 2001ig is the first surviving companion to ever be photographed.

Looking ahead, Ryder and his team hope to precisely determine how many supernovae with stripped envelopes have companions. At present, it is estimated that at least half of them do, while the other half lose their outer enveloped due to stellar winds. Their next goal is to examine completely stripped-envelope supernovae, as opposed to SN 2001ig and SN 1993J, which were only about 90% stripped.

Luckily, they won’t have to wait as long to examine these completely stripped-envelope supernovae, since they don’t have as much shock interaction with gas in their surrounding environment. In short, since they lost their outer envelopes long before they exploded, they fade much faster. This means that the team will only have to wait two to three years before looking for the surviving companions.

Their efforts are also likely to be helped by the deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is scheduled to launch in 2020. Depending on what they find, astronomers may be ready to resolve the mystery of what causes the different types of supernovae, which could also reveal more about the life cycles of stars and the birth of black holes.

Further Reading: NASA, The Astrophysical Journal