Since it was founded in 1984, the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, has been a principal American venue for scientific efforts to discover evidence of extraterrestrial civilizations. In mid-November, the institute sponsored a conference, “Communicating across the Cosmos”, on the problems of devising and understanding messages from other worlds. The conference drew 17 speakers from numerous disciplines, including linguistics, anthropology, archeology, mathematics, cognitive science, philosophy, radio astronomy, and art.

This is the second of four installments of a report on the conference. Today, we’ll look at the SETI Institute’s current efforts to find an extraterrestrial message, and some of their future plans. If they find something, just how much information can we expect to receive? How much can we send?

The idea of using radio to listen for messages from extraterrestrials is as old as radio itself. Radio pioneers Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi both listened for signals from the planet Mars early in the 20th century. The first to listen for messages from the stars was radio astronomer Frank Drake in 1960. Until recently though, SETI projects have been limited and sporadic. That began to change in 2007 when the SETI Institute’s Allen Telescope Array (ATA) started observations.

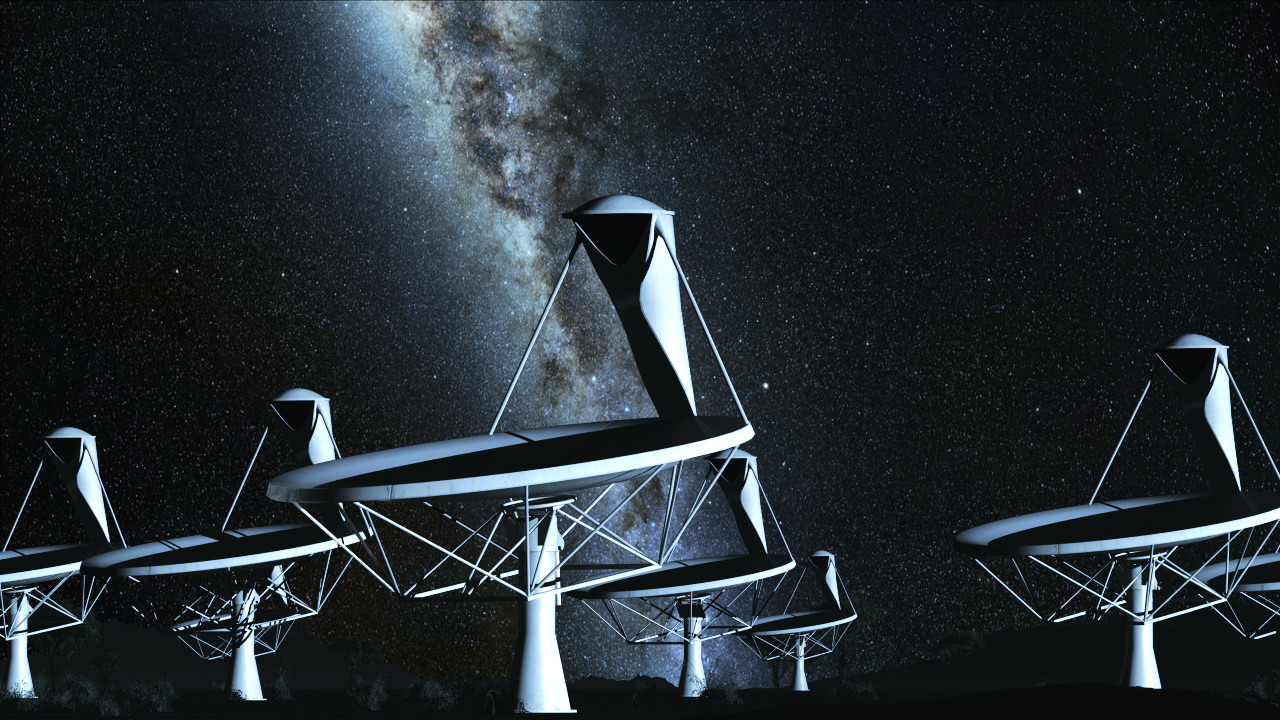

Consisting of 42 small dishes, the ATA is the first radio telescope in the world designed specifically for SETI. The SETI search is currently managed by Jon Richards, an engineer who is an expert on both the system’s hardware and software. He spoke at the conference about the project. The ATA is currently used for SETI research twelve hours out of each day, from 7 pm to 7 am. During the day, the site is operated by Stanford Research International to perform more conventional astronomical studies. When used for such observations, the dishes can function together as an interferometer, generating images of celestial radio sources. To minimize radio interference from human activities, the telescope is sited a six hour drive north of the SETI Institute at the remote Hat Creek Observatory in the Cascade Mountains of Northern California.

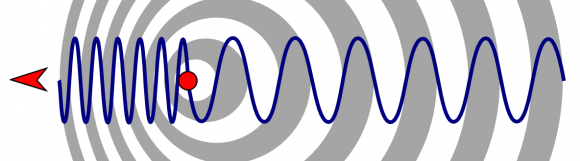

The ATA can detect signals over the range from 1 to 10 GHz. The researchers use several strategies to tell potential ETI signals apart from naturally occurring radio sources in space, and human-made terrestrial interference. Radio emissions from natural sources are smeared over a broad range of frequencies. Artificial signals designed for communication typically pack all of their energy into a very narrow frequency band. To detect such signals, the ATA can resolve frequency differences down to just 1 Hz.

When a radio source is moving with respect to the receiver, it appears to change in frequency. This phenomenon is called the Doppler effect. Because an alien planet and the Earth would be moving in relation to one another, a genuine ETI signal would exhibit the Doppler effect. A source of terrestrial interference that’s fixed to the Earth wouldn’t. If the beam of the telescope is shifted away from the target, a genuine alien signal emanating from a distant point in space would disappear, reappearing when the beam was shifted back. A signal due to local interference wouldn’t.

The ATA is designed to perform these tests automatically whenever it detects a potential candidate signal. To make sure, it repeats the second test five times. If a signal passes the tests, the operator is automatically sent an e-mail, and the candidate signal is entered into a database. Periodically, as a test, the telescope is programed to point in the direction of one of the two Voyager spacecraft. Because these spacecraft are hurtling through deep space beyond the orbit of Neptune, their signals mimic the properties expected from an alien transmission. So far, all the e-mails received have been generated by such tests, and by false alarms. The fateful e-mail announcing the successful detection of an extraterrestrial signal has not yet been sent.

Richards explained that the ATA’s most recent project has been to listen to more than one hundred Earth-like planets discovered by the Kepler space telescope between 2009 and 2012. Next year the ATA’s antenna feeds will get an upgrade that will increase their upper frequency limit to 15 GHz and greatly increase their sensitivity. Both ground-based and Kepler studies have identified numerous Earth-like planets at habitable distances from small dim red dwarf stars. A systematic search of these stars is planned next. If the SETI Institute can find the funding they hope eventually to expand the ATA to 350 dishes.

According to astronomer Jill Tartar, the retired director of the SETI Institute’s Center for SETI Research, the institute is hoping to become involved in a much larger international project; the Square Kilometer Array (SKA). When it begins operations in 2020, the SKA is planned to be the world’s largest radio telescope. It will consist of several thousand dishes and other receivers giving it a radio signal collecting area of one square kilometer. The advantage of having more collecting area is that the telescope is sensitive to fainter signals. If funding allows it to be built in the way currently planned, it will be capable of training multiple simultaneous beams at the sky, some of which Tartar said might be used to mount a continuously ongoing SETI search.

Suppose we did find something. What sort of reply could we send? How much do we have the technological capability to send, if we wanted to? Back in 1974, in the first demonstration of the capacity for interstellar messaging, the Arecibo radio telescope transmitted a mere 210 bytes, and took 3 minutes to do it. The message consisted of a human stick figure and a few other crude symbols and diagrams. Because this primitive effort is still the most well-known example of interstellar radio messaging, prepare yourself for a stunning surprise. According to SETI Institute radio astronomer Seth Shostak, using broadband microwave radio, we could send them the Library of Congress (consisting of 17 million books) in 3 days, and the contents of the World Wide Web (as of 2008) in a comparable time.

Using the shorter optical wavelengths of a laser beam and optical broadband, we could send either one in 20 minutes. Since the extraterrestrials might tune in at any time, we would need to send the transmission over and over again many times. Although our transmissions could be sent in only days or minutes, they would, of course, still take decades or centuries to traverse the light years. This transmission capability presents a stunning opportunity. We can send anything. We can send everything. Could it really be that someday, beings from Tau Ceti will peruse your Facebook page?

So what can we expect from the aliens? Any message we might receive, Seth Shostak thought, would be of one of two possible sorts. A civilization already aware of our existence, he believed, would send us a huge message, rich in information content. This is because even if technological civilizations are fairly common in the galaxy the nearest one might be tens, hundreds, or thousands of light years away. Radio messages traveling at the speed of light will take that long to cross those distances, and decades or centuries will elapse between query and response. If we are contacted, Shostak really does think that we should send the aliens the entire content of the World Wide Web. Civilizations further away than 70 light years from Earth probably wouldn’t know that we exist, because radio signals from Earth haven’t reached them yet. Shostak didn’t think that civilizations would waste precious transmitting time and energy bombarding planets with petabytes of information if they didn’t already know that there was a technological civilization there. Worlds that weren’t known to harbor a civilization, Shostak speculated, might get put on a long list of potentially habitable planets to which the aliens might periodically send a brief “ping” hoping to get a response.

A petabyte of gibberish contains as much information as a petabyte of our world’s greatest art and literature (or tackiest YouTube videos). A petabyte of our world’s greatest art and literature is gibberish to a being who can’t understand it. We could send the aliens truly stunning amounts of information, but can we find some way to ensure that they will understand its meaning? Could we hope to understand an alien message sent to us, or would all those petabytes be for naught? In the next installment, we’ll learn that we face daunting problems.

Part 1: Shouting Into the Darkness

References and Further Readings:

Communicating Across the Cosmos: How can we make ourselves understood by other civilizations in the galaxy, SETI Institute.

N. Atkinson (2012), SETI: The Search Goes On, Universe Today.

S. J. Dick (1996), The Biological Universe: The Twentieth_Century Extraterrestrial Life Debate and the Limits of Science, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

S. Hall (2014), Are We Ready for Contact?, Universe Today.

Allen Telescope Array, SETI Institute.