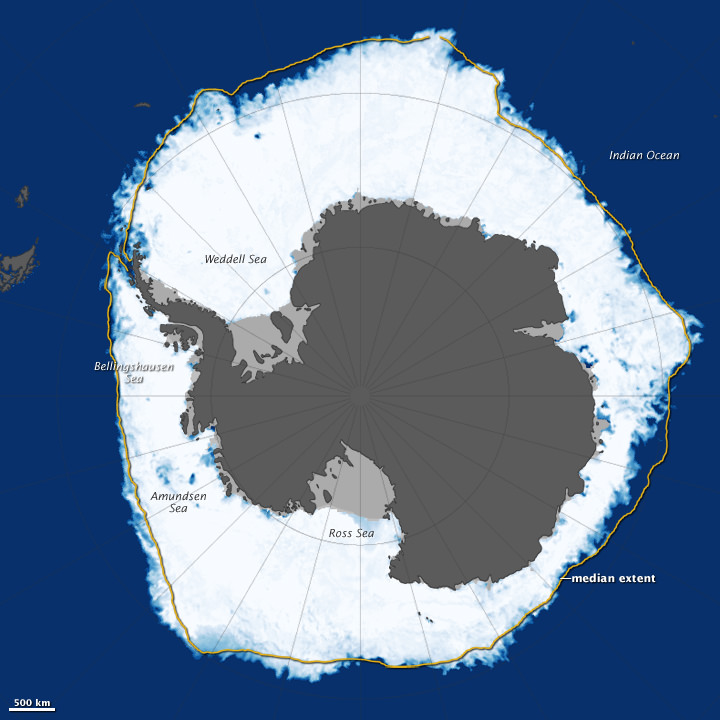

Antarctica’s sea ice is creeping further out in the ocean! New data from a Japanese satellite shows that sea ice surrounding the southern continent in late September reached out over 7.51 million square miles (19.47 million square kilometers).

The extent — a slight increase over 2012’s record of 7.50 million square miles (19.44 million square km) — is the largest recorded instance of Antarctica sea ice since satellite records began, NASA said. Data was recorded using the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2) sensor on the Global Change Observation Mission 1st-Water (GCOM-W1) satellite.

“While researchers continue to study the forces driving the growth in sea ice extent, it is well understood that multiple factors—including the geography of Antarctica, the region’s winds, as well as air and ocean temperatures—all affect the ice,” NASA stated.

Update — see below for a more detailed description of why this is an important clue that climate change IS happening.

“Geography and winds are thought to be especially important. Unlike the Arctic, where sea ice is confined in a basin, Antarctica is a continent surrounded by open ocean. Since its sea ice is unconfined, it is particularly sensitive to changes in the winds. As noted by the National Snow and Ice Data Center, some research has suggested that changes in Antarctic sea ice are caused in part by a strengthening of the westerly winds that flow unhindered in a circle above the Southern Ocean.”

For those thinking that increased sea ice means we can relax about climate change, this humorous video explains the difference between land ice (glaciers) and sea ice (which is generated from snow, rainfall and fresh water). It’s definitely worth four minutes of your time. The part about sea ice starts around 2:45.

UPDATE: Just to clarify:

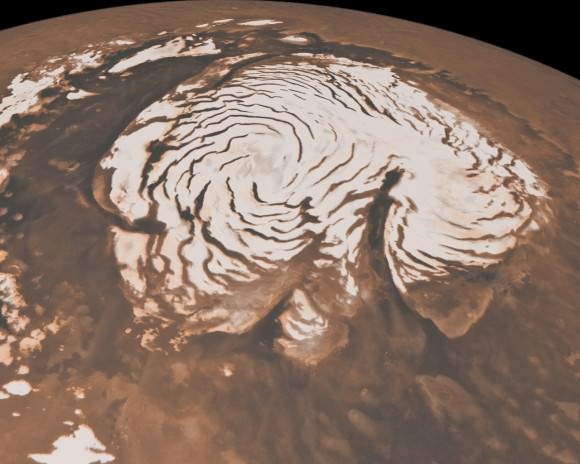

Here’s what the graphic says: “The water around Antarctica is more fresh than it has been in previous years because of increased snow and rainfall as well as in increased contribution of fresh water from melting land ice. This fresh cold water is less dense than the warmer, saltier water below. Previously, that warm salty water would rise, melting the sea ice. But now, bcaus of the lighter fresh water on top, there is less mixing of the ocean’s layer and the surface stays cooler longer. “

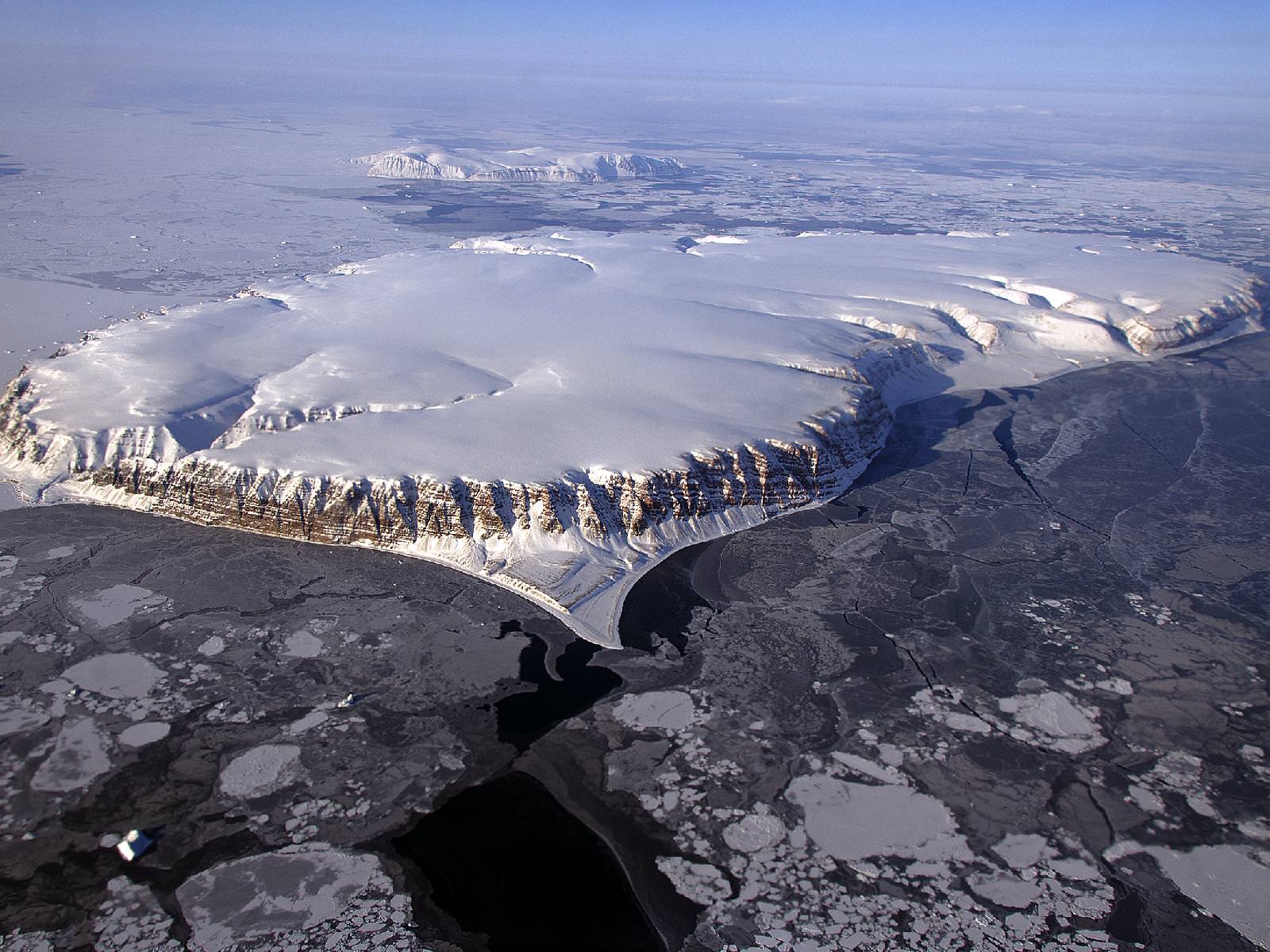

And so, there is increased fresh water because of the melting land ice – due to climate change. There is a fundamental difference between sea ice and land ice. Antarctic land ice is the ice which has accumulated over thousands of years on the Antarctica landmass through snowfall. Antarctic sea ice is entirely different as it is ice which forms in salt water during the winter and almost entirely melts again in the summer.

Importantly, when land ice melts and flows into the oceans global sea levels rise on average; when sea ice melts sea levels do not change measurably but other parts of the climate system are affected, like increased absorption of solar energy by the darker oceans.

See this article on SkepticalScience for additional information.

Source: NASA Earth Observatory