If you’re still scratching your head, trying to figure out all the Higgs Boson news, the great folks from MinutePhysics have put together a new video to explain it all. However, since this is all a little complicated, it’s going to take more than one minute. Parts 2 and 3 are on their way!

Ping-Pong Particles: What the Higgs Does

Unless you’ve been hiding under a chondrite for the past week you’ve heard the news from CERN regarding the discovery of a new particle that exhibits “Higgs-like” qualities. Particle physics isn’t the easiest discipline to wrap one’s head around, and while we’ve recently shared some simplified explanations of what exactly a Higgs boson is, well…here’s another.

Here, BBC’s Jonathan Amos attempts to demonstrate what the Higgs field does, and what part the boson plays. Some Ping-Pong balls, a little sugar, and a cafeteria tray is all it takes to give an idea of how essential this long-sought after subatomic particle is to the Universe. (If only finding it had been that easy!)

Video: BBC News

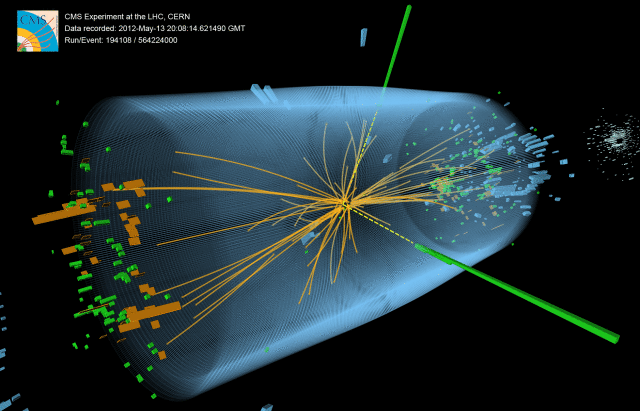

Higgs-like Particle Discovered at CERN

Physicists working at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) have announced the discovery of what they called a “Higgs-like boson” — a particle that resembles the long sought-after Higgs.

“We have reached a milestone in our understanding of nature,” CERN director general Rolf Heuer told scientists and media at a conference near Geneva on July 4, 2012. “The discovery of a particle consistent with the Higgs boson opens the way to more detailed studies, requiring larger statistics, which will pin down the new particle’s properties, and is likely to shed light on other mysteries of our universe.”

Two experiments, ATLAS and CMS, presented their preliminary results, and observed a new particle in the mass region around 125-126 GeV, the expected mass range for the Higgs Boson. The results are based on data collected in 2011 and 2012, with the 2012 data still under analysis. The official results will be published later this month and CERN said a more complete picture of today’s observations will emerge later this year after the LHC provides the experiments with more data.

“We observe in our data clear signs of a new particle, at the level of 5 sigma, in the mass region around 126 GeV. The outstanding performance of the LHC and ATLAS and the huge efforts of many people have brought us to this exciting stage,” said ATLAS experiment spokesperson Fabiola Gianotti, “but a little more time is needed to prepare these results for publication.”

The discovery of the Higgs is big, in that it is the last undiscovered piece of the Standard Model that describes the fundamental make-up of the universe.

Scientists believe that the Higgs boson, named for Scottish physicist Peter Higgs, who first theorized its existence in 1964, is responsible for particle mass, the amount of matter in a particle. According to the theory, a particle acquires mass through its interaction with the Higgs field, which is believed to pervade all of space and has been compared to molasses that sticks to any particle rolling through it.

And so, in theory, the Higgs would be responsible for how particles come together to form matter, and without it, the universe would have remained a formless miss-mash of particles shooting around at the speed of light.

“It’s hard not to get excited by these results,” said CERN Research Director Sergio Bertolucci. “We stated last year that in 2012 we would either find a new Higgs-like particle or exclude the existence of the Standard Model Higgs. With all the necessary caution, it looks to me that we are at a branching point: the observation of this new particle indicates the path for the future towards a more detailed understanding of what we’re seeing in the data.”

A CERN press release says that the next step will be to determine the precise nature of the particle and its significance for our understanding of the universe.

Are its properties as expected for the long-sought Higgs boson, the final missing ingredient in the Standard Model of particle physics? Or is it something more exotic? The Standard Model describes the fundamental particles from which we, and every visible thing in the universe, are made, and the forces acting between them. All the matter that we can see, however, appears to be no more than about 4% of the total. A more exotic version of the Higgs particle could be a bridge to understanding the 96% of the universe that remains obscure. – CERN press release

“We have reached a milestone in our understanding of nature,” said CERN Director General Rolf Heuer. “The discovery of a particle consistent with the Higgs boson opens the way to more detailed studies, requiring larger statistics, which will pin down the new particle’s properties, and is likely to shed light on other mysteries of our universe.”

Positive identification of the new particle’s characteristics will take more time and more experiments. But the scientists feel that whatever form the Higgs particle takes, our knowledge of the fundamental structure of matter is about to take a major step forward.

Lead image caption: Event recorded with the CMS detector in 2012 at a proton-proton centre of mass energy of 8 TeV. The event shows characteristics expected from the decay of the SM Higgs boson to a pair of photons (dashed yellow lines and green towers). The event could also be due to known standard model background processes. Credit: CERN

Source: CERN

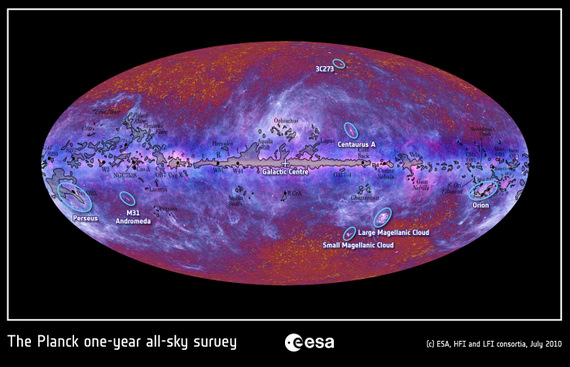

Polar Telescope Casts New Light On Dark Energy And Neutrino Mass

[/caption]

Located at the southermost point on Earth, the 280-ton, 10-meter-wide South Pole Telescope has helped astronomers unravel the nature of dark energy and zero in on the actual mass of neutrinos — elusive subatomic particles that pervade the Universe and, until very recently, were thought to be entirely without measureable mass.

The NSF-funded South Pole Telescope (SPT) is specifically designed to study the secrets of dark energy, the force that purportedly drives the incessant (and apparently still accelerating) expansion of the Universe. Its millimeter-wave observation abilities allow scientists to study the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) which pervades the night sky with the 14-billion-year-old echo of the Big Bang.

Overlaid upon the imprint of the CMB are the silhouettes of distant galaxy clusters — some of the most massive structures to form within the Universe. By locating these clusters and mapping their movements with the SPT, researchers can see how dark energy — and neutrinos — interact with them.

“Neutrinos are amongst the most abundant particles in the universe,” said Bradford Benson, an experimental cosmologist at the University of Chicago’s Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics. “About one trillion neutrinos pass through us each second, though you would hardly notice them because they rarely interact with ‘normal’ matter.”

If neutrinos were particularly massive, they would have an effect on the large-scale galaxy clusters observed with the SPT. If they had no mass, there would be no effect.

The SPT collaboration team’s results, however, fall somewhere in between.

Even though only 100 of the 500 clusters identified so far have been surveyed, the team has been able to place a reasonably reliable preliminary upper limit on the mass of neutrinos — again, particles that had once been assumed to have no mass.

Previous tests have also assigned a lower limit to the mass of neutrinos, thus narrowing the anticipated mass of the subatomic particles to between 0.05 – 0.28 eV (electron volts). Once the SPT survey is completed, the team expects to have an even more confident result of the particles’ masses.

“With the full SPT data set we will be able to place extremely tight constraints on dark energy and possibly determine the mass of the neutrinos,” said Benson.

“We should be very close to the level of accuracy needed to detect the neutrino masses,” he noted later in an email to Universe Today.

Such precise measurements would not have been possible without the South Pole Telescope, which has the ability due to its unique location to observe a dark sky for very long periods of time. Antarctica also offers SPT a stable atmosphere, as well as very low levels of water vapor that might otherwise absorb faint millimeter-wavelength signals.

“The South Pole Telescope has proven to be a crown jewel of astrophysical research carried out by NSF in the Antarctic,” said Vladimir Papitashvili, Antarctic Astrophysics and Geospace Sciences program director at NSF’s Office of Polar Programs. “It has produced about two dozen peer-reviewed science publications since the telescope received its ‘first light’ on Feb. 17, 2007. SPT is a very focused, well-managed and amazing project.”

The team’s findings were presented by Bradford Benson at the American Physical Society meeting in Atlanta on April 1.

Particle Physicists Put the Squeeze on the Higgs Boson; Look for Conclusive Results in 2012

[/caption]

With “freshly squeezed” plots from the latest data garnered by two particle physics experiments, teams of scientists from the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, the European Center for Nuclear Research, said Tuesday they had recorded “tantalizing hints” of the elusive subatomic particle known as the Higgs Boson, but cannot conclusively say it exists … yet. However, they predict that 2012 collider runs should bring enough data to make the determination.

“The very fact that we are able to show the results of very sophisticated analysis just one month after the last bit of data we used has been recorded is very reassuring,” Dr. Greg Landsberg, physics coordinator for the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) detector at the LHC told Universe Today. “It tells you how quick the turnaround time is. This is truly unprecedented in the history of particle physics, with such large and complex experiments producing so much data, and it’s very exciting.”

For now, the main conclusion of over 6,000 scientists on the combined teams from CMS and the ATLAS particle detectors is that they were able to constrain the mass range of the Standard Model Higgs boson — if it exists — to be in the range of 116-130 GeV by the ATLAS experiment, and 115-127 GeV by CMS.

The Standard Model is the theory that explains the interactions of subatomic particles – which describes ordinary matter that the Universe is made of — and on the whole works very well. But it doesn’t explain why some particles have mass and others don’t, and it also doesn’t describe the 96% of the Universe that is invisible.

In 1964, physicist Peter Higgs and colleagues proposed the existence of a mysterious energy field that interacts with some subatomic particles more than others, resulting in varying values for particle mass. That field is known as the Higgs field, and the Higgs Boson is the smallest particle of the Higgs field. But the Higgs Boson hasn’t been discovered yet, and one of the main reasons the LHC was built was to try to find it.

To look for these tiny particles, the LHC smashes high-energy protons together, converting some energy to mass. This produces a spray of particles which are picked up by the detectors. However, the discovery of the Higgs relies on observing the particles these protons decay into rather than the Higgs itself. If they do exist, they are very short lived and can decay in many different ways. The problem is that many other processes can also produce the same results.

How can scientists tell the difference? A short answer is that if they can figure out all the other things that can produce a Higgs-like signal and the typical frequency at which they will occur, then if they see more of these signals than current theories suggest, that gives them a place to look for the Higgs.

The experiments have seen excesses in similar ranges. And as the CERN press release noted, “Taken individually, none of these excesses is any more statistically significant than rolling a die and coming up with two sixes in a row. What is interesting is that there are multiple independent measurements pointing to the region of 124 to 126 GeV.”

“This is very promising,” said Landsberg, who is also a professor at Brown University. “This shows that both experiments understand what is going on with their detectors very, very well. Both calibrations saw excesses at low masses. But unfortunately the nature of our process is statistical and statistics is known to play funny tricks once in a while. So we don’t really know — we don’t have enough evidence to know — if what we saw is a glimpse of the Higgs Boson or these are just statistical fluctuations of the Standand Model process which mimic the same type of signatures as would come if the Higgs Boson is produced.”

Landsberg said the only way to cope with statistics is to get more data, and the scientists need to increase the size of the data samples considerably in order to definitely answer the question on whether the Higgs Boson exists at the mass of 125 GeV or any mass range which hasn’t been excluded yet.

The good news is that loads of data are coming in 2012.

“We hope to quadruple the data sample collected this year,” Landsberg said. “And that should give us enough statistical confidence to essentially solve this puzzle and tell the world whether we saw the first glimpses of the Higgs Boson. As the team showed today, we will keep increasing until we reach a level of statistical significance which is considered to be sufficient for discovery in our field.”

Landsberg said that within this small range, there is not much room for the Higgs to hide. “This is very exciting, and it tells you that we are almost there. We have enough sensitivity and beautiful detectors; we need just a little bit more time and a little more data. I am very hopeful we should be able to say something definitive by sometime next year.”

So the suspense is building and 2012 could be the year of the Higgs.

More info: CERN press release, ArsTechnica

Neutrinos Still Breaking Speed Limits

[/caption]

New test results are in from OPERA and it seems those darn neutrinos, they just can’t keep their speed down… to within the speed of light, that is!

A report released in September by scientists working on the OPERA project (Oscillation Project with Emulsion-tracking Apparatus) at Italy’s Gran Sasso research lab claimed that neutrinos emitted from CERN 500 miles away in Geneva arrived at their detectors 60 nanoseconds earlier than expected, thus traveling faster than light. This caused no small amount of contention in the scientific community and made news headlines worldwide – and rightfully so, as it basically slaps one of the main tenets of modern physics across the face.

Of course the scientists at OPERA were well aware of this, and didn’t make such a proclamation lightly; over two years of repeated research was undergone to make sure that the numbers were accurate… as well as could be determined, at least. And they were more than open to having their tests replicated and the results reviewed by their peers. In all regards their methods were scientific yet skepticism was widespread… even within OPERA’s own ranks.

One of the concerns that arose regarding the discovery was in regards to the length of the neutrino beam itself, emitted from CERN and received by special detector plates at Gran Sasso. Researchers couldn’t say for sure that any neutrinos detected were closer to the beginning of the beam versus the end, a disparity (on a neutrino-sized scale anyway) of 10.5 microseconds… that’s 10.5 millionths of a second! And so in October, OPERA requested that proton pulses be resent – this time lasting only 3 nanoseconds each.

The results were the same. The neutrinos arrived at Gran Sasso 60 nanoseconds earlier than anticipated: faster than light.

The test was repeated – by different teams, no less – and so far 20 such events have been recorded. Each time, the same.

Faster. Than light.

What does this mean? Do we start tearing pages out of physics textbooks? Should we draw up plans for those neutrino-powered warp engines? Does Einstein’s theory of relativity become a quaint memento of what we used to believe?

Hardly. Or, at least, not anytime soon.

OPERA’s latest tests have managed to allay one uncertainty regarding the results, but plenty more remain. One in particular is the use of GPS to align the clocks at the beginning and end of the neutrino beam. Since the same clock alignment system was used in all the experiments, it stands that there may be some as-of-yet unknown factor concerning the GPS – especially since it hasn’t been extensively used in the field of high-energy particle physics.

In addition, some scientists would like to see more results using other parts of the neutrino detector array.

Of course, like any good science, replication of results is a key factor for peer acceptance. And thus Fermilab in Batavia, Illinois will attempt to perform the same experiment with its MINOS (Main Injector Neutrino Oscillation Search) facility, using a precision matching OPERA’s.

MINOS hopes to have its independent results as early as next year.

No tearing up any textbooks just yet…

Read more in the Nature.com news article by Eugenie Samuel Reich. The new result was released on the arXiv preprint server on November 17. (The original September 2011 OPERA team paper can be found here.)

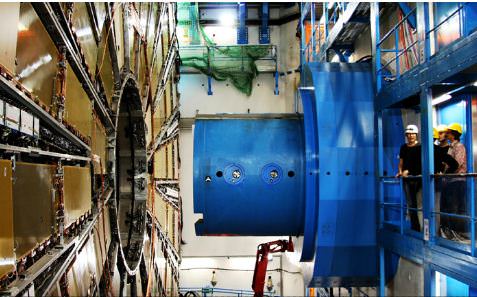

Large Hadron Collider Finishes 2011 Proton Run

[/caption]

The world’s largest and highest-energy particle accelerator has been busy. At 5:15 p.m. on October 30, 2011, the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland reached the end of its current proton run. It came after 180 consecutive days of operation and four hundred trillion proton collisions. For the second year, the LHC team has gone beyond its operational objectives – sending more experimental data at a higher rate. But just what has it done?

When this year’s project started, its goal was to produce a surplus of data known to physicists as one inverse femtobarn. While that might seem like a science fiction term, it’s a science fact. An inverse femtobarn is a measurement of particle collision events per femtobarn – which is equal to about 70 million million collisions. The first inverse femtobarn came on June 17th, and just in time to prepare the stage for major physics conferences requiring the data be moved up to five inverse femtobarns. The incredible number of collisions was reached on October 18, 2011 and then surpassed as almost six inverse femtobarns were delivered to each of the two general-purpose experiments – ATLAS and CMS.

“At the end of this year’s proton running, the LHC is reaching cruising speed,” said CERN’s Director for Accelerators and Technology, Steve Myers. “To put things in context, the present data production rate is a factor of 4 million higher than in the first run in 2010 and a factor of 30 higher than at the beginning of 2011.”

But that’s not all the LHC delivered this year. This year’s proton run also shut out the accessible hiding space for the highly prized Higgs boson and supersymmetric particles. This certainly put the Standard Model of particle physics and our understanding of the primordial Universe to the test!

“It has been a remarkable and exciting year for the whole LHC scientific community, in particular for our students and post-docs from all over the world. We have made a huge number of measurements of the Standard Model and accessed unexplored territory in searches for new physics. In particular, we have constrained the Higgs particle to the light end of its possible mass range, if it exists at all,” said ATLAS Spokesperson Fabiola Gianotti. “This is where both theory and experimental data expected it would be, but it’s the hardest mass range to study.”

“Looking back at this fantastic year I have the impression of living in a sort of a dream,” said CMS Spokesperson Guido Tonelli. “We have produced tens of new measurements and constrained significantly the space available for models of new physics and the best is still to come. As we speak hundreds of young scientists are still analysing the huge amount of data accumulated so far; we’ll soon have new results and, maybe, something important to say on the Standard Model Higgs Boson.”

“We’ve got from the LHC the amount of data we dreamt of at the beginning of the year and our results are putting the Standard Model of particle physics through a very tough test ” said LHCb Spokesperson Pierluigi Campana. “So far, it has come through with flying colours, but thanks to the great performance of the LHC, we are reaching levels of sensitivity where we can see beyond the Standard Model. The researchers, especially the young ones, are experiencing great excitement, looking forward to new physics.”

Over the next few weeks, the LHC will be further refining the 2011 data set with an eye to improving our understanding of physics. And, while it’s possible we’ll learn more from current findings, look for a leap to a full 10 inverse femtobarns which may yet be possible in 2011 and projected for 2012. Right now the LHC is being prepared for four weeks of lead-ion running… an “attempt to demonstrate that large can also be agile by colliding protons with lead ions in two dedicated periods of machine development.” If this new strand of LHC operation happens, science will soon be using protons to check out the internal machinations of much heftier structures – like lead ions. This directly relates to quark-gluon plasma, the surmised primordial conglomeration of ordinary matter particles from which the Universe evolved.

“Smashing lead ions together allows us to produce and study tiny pieces of primordial soup,” said ALICE Spokesperson Paolo Giubellino, “but as any good cook will tell you, to understand a recipe fully, it’s vital to understand the ingredients, and in the case of quark-gluon plasma, this is what proton-lead ion collisions could bring.”

Original Story Source: CERN Press Release.

Q&A with Brian Cox, part 1: Recent Hints of the Higgs

[/caption]

At two separate conferences in July, particle physicists announced some provoking news about the Higgs boson, and while the Higgs has not yet been found, physicists are continuing to zero in on the elusive particle. Universe Today had the chance to talk with Professor Brian Cox about these latest findings, and he says that within six to twelve months, physicists should be able to make a definite statement about the existence of the Higgs particle. Cox is the Chair in Particle Physics at the University of Manchester, and works on the ATLAS experiment (A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS) at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN. But he’s also active in the popularization of science, specifically with his new television series and companion book, Wonders of the Universe, a follow up to the 2010 Peabody Award-winning series, Wonders of the Solar System.

Universe Today readers will have a chance to win a copy of the book, so stay tuned for more information on that. But today, enjoy the first of a three-part interview with Cox:

Universe Today: Can you tell us about your work with ATLAS and its potential for finding things like extra dimensions, the unification of forces or dark matter?

Brian Cox: The big question is the origin and mass of the universe. It is very, very important because it is not an end in itself. It is a fundamental part of Quantum Field Theory, which is our theory of three of the four forces of nature. So if you ask the question on the most basic level of how does the universe work, there are only two pillars of our understanding at the moment. There is Einstein’s Theory of General Relatively, which deals with gravity — the weakest force in the Universe that deals with the shape of space and time and all those things. But everything else – electromagnetism, the way the atomic nuclei works, the way molecules work, chemistry, all that – everything else is what’s called a Quantum Field Theory. Embedded in that is called the Standard Model of particle physics. And embedded in that is this mechanism for generating mass, and it’s just so fundamental. It’s not just kind of an interesting add-on, it’s right in the heart of the way the theory works.

So, understanding whether our current picture of the Universe is right — and if there is this thing called the Higgs mechanism or whether there is something else going on — is critical to our progress because it is built into that picture. There are hints in the data recently that maybe that mechanism is right. We have to be careful. It’s not a very scientific thing to say that we have hints. We have these thresholds for scientific discovery, and we have them for a reason, because you get these statistical flukes that appear in the data and when you get more data they go away again.

The statement from CERN now is that if they turn out to be more than just fluctuations, really, within six months we should be able to make some definite statement about the existence of the Higgs particle.

I think it is very important to emphasize that this is not just a lot of particle physicists looking for particles because that’s their job. It is the fundamental part of our understanding of three of the four forces of nature.

UT : So these very interesting results from CERN and the Tevatron at Fermilab giving us hints about the Higgs, could you can talk little bit more about that and your take on the latest findings?

COX: The latest results were published in a set of conferences a few weeks ago and they are just under what is called the Three Sigma level. That is the way of assessing how significant the results are. The thing about all quantum theory and particle physics in general, is it is all statistical. If you do this a thousand times, then three times this should happen, and eight times that should happen. So it’s all statistics. As you know if you toss a coin, it can come up heads ten times, there is a probability for that to happen. It doesn’t mean the coin is weighted or there’s something wrong with it. That’s just how statistics is.

So there are intriguing hints that they have found something interesting. Both experiments at the Large Hadron Collider, the ATLAS and the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) recently reported “excess events” where there were more events than would be expected if the Higgs does not exist. It is about the right mass: we think the Higgs particle should be somewhere between about 120 and 150 gigaelectron volts [GeV—a unit of energy that is also a unit of mass, via E = mc2, where the speed of light, c, is set to a value of one] which is the expected mass range of the Higgs. These hints are around 140, so that’s good, it’s where it should be, and it is behaving in the way that it is predicted to by the theory. The theory also predicts how it should decay away, and what the probability should be, so all the data is that this is consistent with the so-called standard model Higgs.

But so far, these events are not consistently significant enough to make the call. It is important that the Tevatron has glimpsed it as well, but that has even a lower significance because that was low energy and not as many collisions there. So you’ve got to be scientific about things. There is a reason we have these barriers. These thresholds are to be cleared to claim discoveries. And we haven’t cleared it yet.

But it is fascinating. It’s the first time one of these rumors have been, you know, not just nonsense. It really is a genuine piece of exciting physics. But you have to be scientific about these things. It’s not that we know it is there and we’re just not going to announce it yet. It’s the statistics aren’t here yet to claim the discovery.

UT : Well, my next question was going to be, what happens next? But maybe you can’t really answer that because all you can do is keep doing the research!

COX: The thing about the Higgs, it is so fundamentally embedded in quantum theory. You’ve got to explore it because it is one thing to see a hint of a new particle, but it’s another thing to understand how that particle behaves. There are lots of different ways the Higgs particles can behave and there are lots of different mechanisms.

There is a very popular theory called supersymmetry which also would explain dark matter, one of the great mysteries in astrophysics. There seems to be a lot of extra stuff in the Universe that is not behaving the way that particles of matter that we know of behave, and with five times more “stuff” as what makes up everything we can see in the Universe. We can’t see dark matter, but we see its gravitational influence. There are theories where we have a very strong candidate for that — a new kind of particle called a supersymmetry particles. There are five Higgs particles in them rather than one. So the next question is, if that is a Higgs-like particle that we’ve discovered, then what is it? How does it behave? How does it talk to the other particles?

And then there are a huge amount of questions. The Higgs theory as it is now doesn’t explain why the particles have the masses they do. It doesn’t explain why the top quark, which is the heaviest of the fundamental particles, is something like 180 times heavier than the proton. It’s a tiny point-like thing with no size but it’s 180 times the mass of a proton! That is heavier than some of the heaviest atomic nuclei!

Why? We don’t know.

I think it is correct to say there is a door that needs to be opened that has been closed in our understanding of the Universe for decades. It is so fundamental that we’ve got to open it before we can start answering these further questions, which are equally intriguing but we need this answered first.

UT: When we do get some of these questions answered, how is that going to change our outlook and the way that we do things, or perhaps the way YOU do things, anyway! Maybe not us regular folks…

COX: Well, I think it will – because this is part of THE fundamental theory of the forces of nature. So quantum theory in the past has given us an understanding, for example, of the way semiconductors work, and it underpins our understanding of modern technology, and the way chemistry works, the way that biological systems work – it’s all there. This is the theory that describes it all. I think having a radical shift and deepening in understanding of the basic laws of nature will change the way that physics proceeds in 21st century, without a doubt. It is that fundamental. So, who knows? At every paradigm shift in science, you never really could predict what it was going to do; but the history of science tells you that it did something quite remarkable.

There is a famous quote by Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin, who said that when he woke up on a certain September morning of 1928, he certainly didn’t expect to revolutionize modern medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic. He said that in hindsight, but he just discovered some mold, basically, but there it was.

But it was fundamental and that is the thing to emphasize.

Some of our theories, you look at them and wonder how we worked them! The answer is mathematically, the same way that Einstein came up with General Relativity, with mathematical predictions. It is remarkable we’ve been able to predict something so fundamental about the way that empty space behaves. We might turn out to be right.

Tomorrow: Part 2: The space exploration and hopes for the future

Find out more about Brian Cox at his website, Apollo’s Children

AMS Now Attached to the Space Station, Ready to Observe the Invisible Universe

The long-awaited Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a particle physics detector that could unlock mysteries about dark matter and other cosmic radiation, has now been installed outside the International Space Station. It is the largest and most complex scientific instrument yet on board the orbiting laboratory, and will examine ten thousand cosmic-ray hits every minute, looking for nature’s best-kept particle secrets, searching for clues into the fundamental nature of matter.

“Thank you very much for the great ride and safe delivery of AMS to the station,” said Dr. Samuel Ting, speaking via radio to the crew on orbit who installed the AMS. Ting is the AMS Principal Investigator who has worked on the project for close to 20 years. “Your support and fantastic work have taken us one step closer to realizing the science potential of AMS. With your help, for the next 20 years, AMS on the station will provide us a better understanding of the origin of the universe.”

“Thank you, Sam,” Endeavour commander Mark Kelly radioed back, “I was just looking out the window of the orbiter and AMS looks absolutely fantastic on the truss. I know you guys are really excited and you’re probably getting data and looking at it already.”

By collecting and measuring vast numbers of cosmic rays and their energies, particle physicists hope to understand more about how and where they are born, since a long-standing mystery is where cosmic rays originate. They could be created in the magnetic fields of exploded stars, or perhaps in the hearts of active galaxies, or maybe in places as yet unseen by astronomers.

The AMS is actually AMS-02 – a prototype of the instrument, AMS-01, was launched on board the space shuttle in 1998, and showed great potential. But Ting and his collaborators from around the world knew that to make a significant contribution to particle science, they needed a detector that could be in space for a long period of time.

AMS-02 will operate on the ISS until at least 2020, and hopefully longer, depending on the life of the space station.

[/caption]

The AMS will also search for antimatter within the cosmic rays, and attempt to determine whether the antimatter is formed from collisions between particles of dark matter, the mysterious substance that astronomers believe may make up about 22% of the Universe.

There is also the remote chance that AMS-02 will detect a particle of anti-helium, left over from the Big Bang itself.

“The most exciting objective of AMS is to probe the unknown; to search for phenomena which exist in nature that we have not yet imagined nor had the tools to discover,” said Ting.

For more information about the AMS, NASA has a detailed article.

Source: ESA, NASA TV

Did the Early Universe Have Just One Dimension?

[/caption]

From a University of Buffalo press release:

Did the early universe have just one spatial dimension? That’s the mind-boggling concept at the heart of a theory that physicist Dejan Stojkovic from the University at Buffalo and colleagues proposed in 2010. They suggested that the early universe — which exploded from a single point and was very, very small at first — was one-dimensional (like a straight line) before expanding to include two dimensions (like a plane) and then three (like the world in which we live today).

The theory, if valid, would address important problems in particle physics.

Now, in a new paper in Physical Review Letters, Stojkovic and Loyola Marymount University physicist Jonas Mureika describe a test that could prove or disprove the “vanishing dimensions” hypothesis.

Because it takes time for light and other waves to travel to Earth, telescopes peering out into space can, essentially, look back into time as they probe the universe’s outer reaches.

Gravitational waves can’t exist in one- or two-dimensional space. So Stojkovic and Mureika have reasoned that the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), a planned international gravitational observatory, should not detect any gravitational waves emanating from the lower-dimensional epochs of the early universe.

Stojkovic, an assistant professor of physics, says the theory of evolving dimensions represents a radical shift from the way we think about the cosmos — about how our universe came to be.

The core idea is that the dimensionality of space depends on the size of the space we’re observing, with smaller spaces associated with fewer dimensions. That means that a fourth dimension will open up — if it hasn’t already — as the universe continues to expand.

The theory also suggests that space has fewer dimensions at very high energies of the kind associated with the early, post-big bang universe.

If Stojkovic and his colleagues are right, they will be helping to address fundamental problems with the standard model of particle physics, including the following:

The incompatibility between quantum mechanics and general relativity. Quantum mechanics and general relativity are mathematical frameworks that describe the physics of the universe. Quantum mechanics is good at describing the universe at very small scales, while relativity is good at describing the universe at large scales. Currently, the two theories are considered incompatible; but if the universe, at its smallest levels, had fewer dimensions, mathematical discrepancies between the two frameworks would disappear.

Physicists have observed that the expansion of the universe is speeding up, and they don’t know why. The addition of new dimensions as the universe grows would explain this acceleration. (Stojkovic says a fourth dimension may have already opened at large, cosmological scales.)

The standard model of particle physics predicts the existence of an as yet undiscovered elementary particle called the Higgs boson. For equations in the standard model to accurately describe the observed physics of the real world, however, researchers must artificially adjust the mass of the Higgs boson for interactions between particles that take place at high energies. If space has fewer dimensions at high energies, the need for this kind of “tuning” disappears.

“What we’re proposing here is a shift in paradigm,” Stojkovic said. “Physicists have struggled with the same problems for 10, 20, 30 years, and straight-forward extensions of the existing ideas are unlikely to solve them.”

“We have to take into account the possibility that something is systematically wrong with our ideas,” he continued. “We need something radical and new, and this is something radical and new.”

Because the planned deployment of LISA is still years away, it may be a long time before Stojkovic and his colleagues are able to test their ideas this way.

However, some experimental evidence already points to the possible existence of lower-dimensional space.

Specifically, scientists have observed that the main energy flux of cosmic ray particles with energies exceeding 1 teraelectron volt — the kind of high energy associated with the very early universe — are aligned along a two-dimensional plane.

If high energies do correspond with lower-dimensional space, as the “vanishing dimensions” theory proposes, researchers working with the Large Hadron Collider particle accelerator in Europe should see planar scattering at such energies.

Stojkovic says the observation of such events would be “a very exciting, independent test of our proposed ideas.”

Sources: EurekAlert, Physical Review Letters.