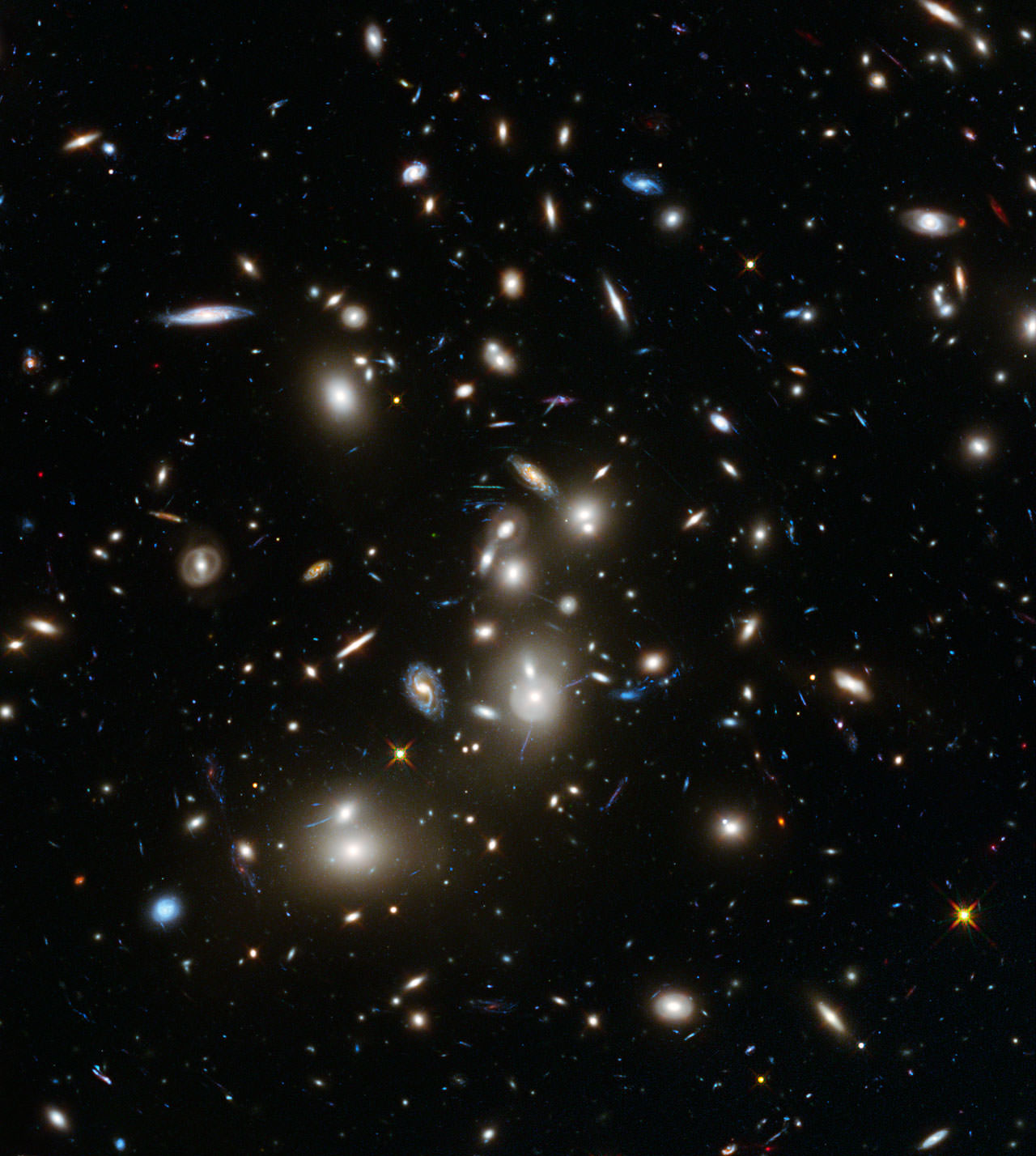

In a patch of sky 3.5 billion light-years away there are hazy elliptical galaxies, colorful spirals, blue arcs and distorted shapes seen clumping together. It’s the result of a vast cosmic collision that took place over the course of 350 million years.

The mess is a treasure trove of information for astronomers, allowing them to piece together the history of a cosmic pile-up of multiple galaxy clusters.

But now astronomers are digging through the nearby darkness. They’re eyeing the remnant stars that were cast adrift in intergalactic space. These stars should emit a faint glow known as intracluster light that — until now — has mostly remained a subject of speculation.

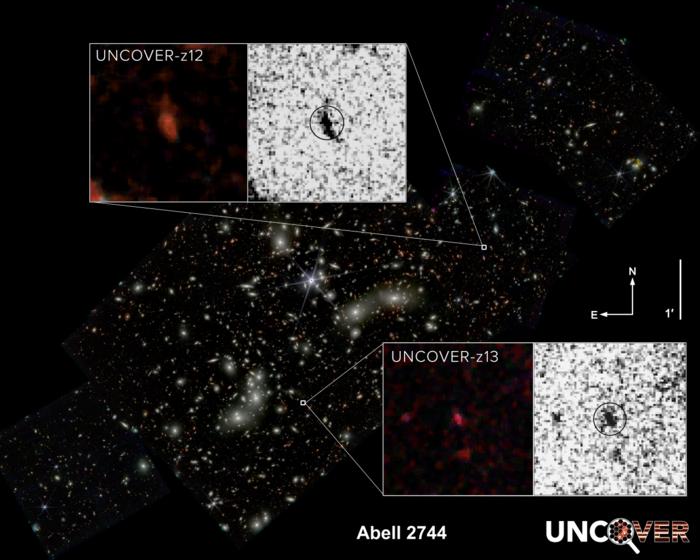

Mireia Montes and Ignacio Trujillo, both from the University of La Laguna, Spain, have used the Hubble Space Telescope to observe the aforementioned cluster, Abel 2744, in exquisite detail. The cluster has already earned the nickname Pandora’s Cluster for its violent past.

The team looked at both visible and near-infrared color images of the cluster, and then split these color images by brightness. This allowed Montes and Trujillo to pinpoint the color of the cluster’s faintest glow and therefore glean the ghost stars’ age, chemical content, and total mass.

Compared to stars within the cluster’s galaxies, the ghost stars emit bluer light and are therefore rich in heavier elements like oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen. So the scattered stars must be second- or third-generation stars enriched by previous supernovae. But they’re still between three and nine billion years younger than the stars within the cluster’s galaxies.

The team estimates that the combined light of about 100 billion outcast stars contributes approximately six percent of the cluster’s brightness.

But how did the stars get thrown from their respective galaxies in the first place? This new forensic evidence suggests that violent collisions tore apart between four and six Milky Way-size galaxies, scattering their stars into intergalactic space.

“The Hubble data revealing the ghost light are important steps forward in understanding the evolution of galaxy clusters,” said Trujillo in a news release. “It is also amazingly beautiful in that we found the telltale glow by utilizing Hubble’s unique capabilities.”

Abell 2744 is only one target in Hubble’s Frontier Fields program, which will map five more galaxy clusters in superb detail.

The results have been published in the Astrophysical Journal and are available online.