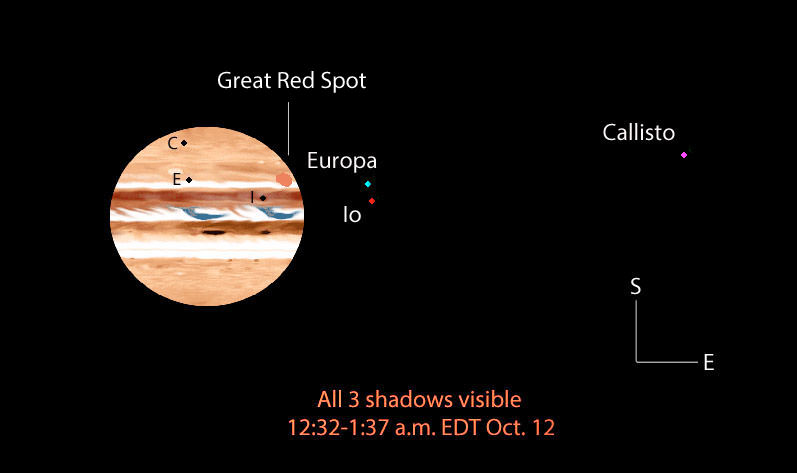

Talk about a great fall lineup. Three of Jupiter’s four brightest moons plan a rare show for telescopic observers on Friday night – Saturday morning Oct. 11-12. For a span of just over an hour, Io, Europa and Callisto will simultaneously cast shadows on the planet’s cloud tops, an event that hasn’t happened since March 28, 2004.

Who doesn’t remember their first time looking at Jupiter and his entourage of dancing moons in a telescope? Because each moves at a different rate depending on its distance from the planet, they’re constantly on the move like kids in a game of musical chairs. Every night offers a different arrangement.

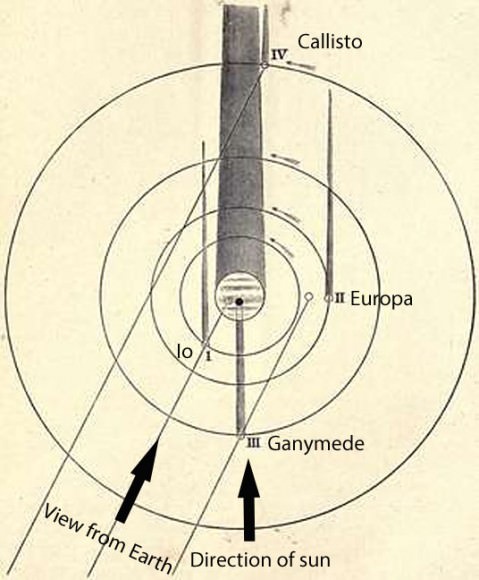

Some nights all four of the brightest are strung out on one side of the planet, other nights only two or three are visible, the others hidden behind Jupiter’s “plus-sized” globe. Occasionally you’ll be lucky enough to catch the shadow of one of moons as it transits or crosses in front of the planet. We call the event a shadow transit, but to someone watching from Jupiter, the moon glides in front of the sun to create a total solar eclipse.

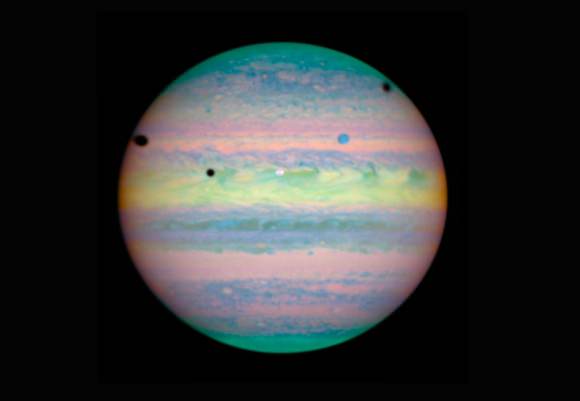

Since the sun is only 1/5 as large from Jupiter as seen from Earth, all four moons are large enough to completely cover the sun and cast inky shadows. To the eye they look like tiny black dots of varying sizes. Europa, the smallest, mimics a pinprick. The shadows of Io and Callisto are more substantial. Ganymede, the solar system’s largest moon at 3,269 miles (5,262 km), looks positively plump compared to the others. Even a small telescope magnifying around 50x will show it.

The three inner satellites – Io, Europa and Ganymede – have shadow transits every orbit. Distant Callisto only transits when Jupiter’s tilt relative to Earth is very small, i.e. the plane of the planet’s moons is nearly edge-on from our perspective. Callisto transits occur in alternating “seasons” lasting about 3 years apiece. Three years of shadow play are followed by three years of shadowless misses. Single transits are fairly common; you can find tables of them online like this one from Project Pluto or plug in time and date into a free program like Meridian for a picture and list of times.

Seeing two shadows inch across Jupiter’s face is very uncommon, and three are as rare as a good hair day for Donald Trump. Averaged out, triple transits occur once or twice a decade. Friday night Oct. 11 each moon enters like actors in a play. Callisto appears first at 11:12 p.m. EDT followed by Europa and then Io. By 12:32 a.m. all three are in place.

Catch them while you can. Groups like these don’t last long. A little more than an hour later Callisto departs, leaving just two shadows. You’ll find the details below. All times are Eastern Daylight or EDT. Subtract one hour for Central time and add four hours for BST (British Summer Time):

* Callisto’s shadow enters the disk – 11:12 p.m. Oct. 11

* Europa – 11:24 p.m.

* Io – 12:32 a.m.

** TRIPLE TRANSIT from 12:32 – 1:37 a.m.

* Callisto departs – 1:37 a.m.

* Europa departs – 2:01 a.m.

* Io departs – 2:44 a.m.

The triple transit will be seen across the eastern half of the U.S., Europe and western Africa. Those living on the East Coast have the best view in the U.S. with Jupiter some 20-25 degrees high in the northeastern sky around 1 a.m. local time. Things get dicier in the Midwest where Jupiter climbs to only 5-10 degrees. From the mountain states the planet won’t rise until Callisto’s shadow has left the disk, leaving a two-shadow consolation prize. If you live in the Pacific time zone and points farther west, you’ll unfortunately miss the event altogether.

Key to seeing all three shadows clearly, especially if Jupiter is low in the sky, is steady air or what skywatchers call “good seeing”. The sky can be so clear you’d swear there’s a million stars up there, but a look through the telescope will sometimes show dancing, blurry images due to invisible air turbulence. That’s “bad seeing”. Unfortunately, bad seeing is more common near the horizon where we peer through a greater thickness of atmosphere. But don’t let that keep you inside Friday night. With a spell of steady air, all you need is a 4-inch or larger telescope magnifying around 100x to spot all three.

If bad weather blocks the view, there are two more triple transits coming up soon – a 95-minute-long event on June 3, 2014 starring Europa, Ganymede and Callisto (not visible in the Americas) and a 25-minute show on Jan. 24, 2015 featuring Io, Europa and Callisto and visible across Western Europe and the Americas. That’s it until dual triple transits in 2032.