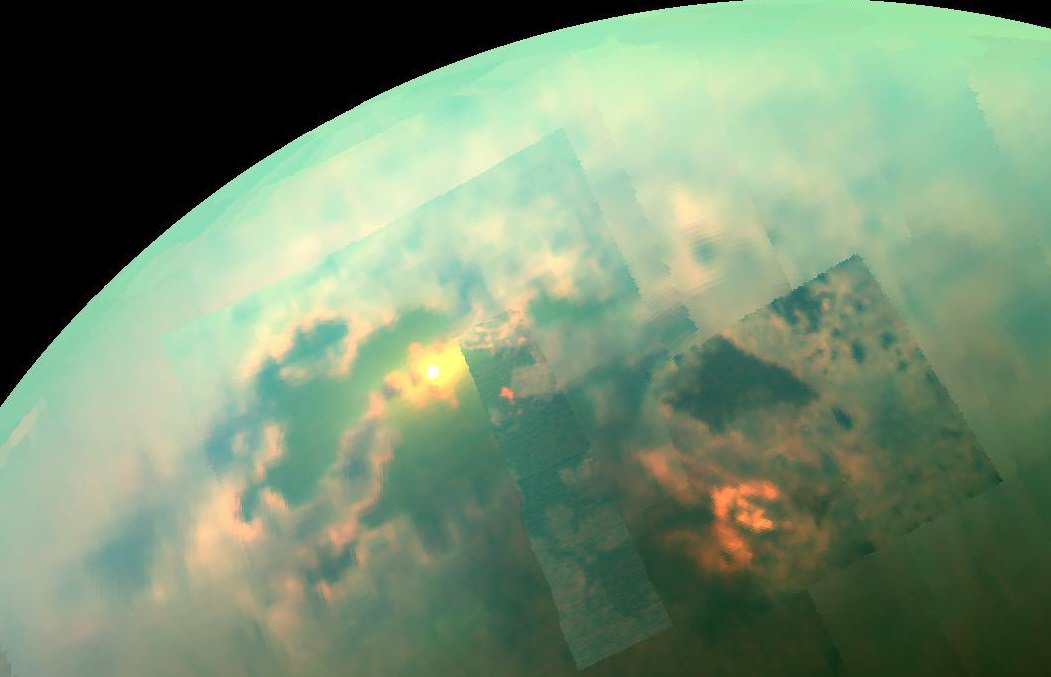

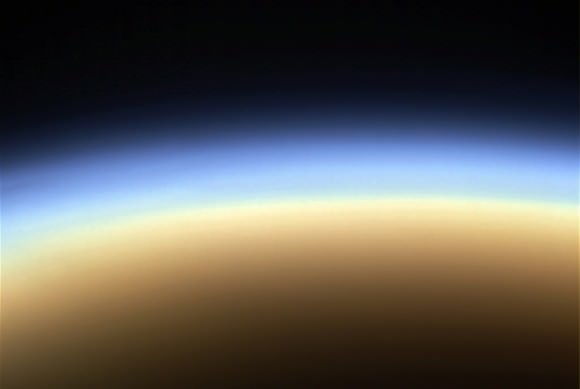

Titan is tough moon to study, thanks to its incredibly thick and hazy atmosphere. But when astronomers have ben able to sneak a peak beneath its methane clouds, they have spotted some very intriguing features. And some of these, interestingly enough, are reminiscent of geographical features here on Earth. For instance, Titan is the only other body in the Solar System that is known to have a cycle where liquid is exchanged between the surface and the atmosphere.

For example, previous images provided by NASA’s Cassini mission showed indications of steep-sided canyons in the northern polar region that appeared to be filled with liquid hydrocarbons, similar to river valleys here on Earth. And thanks to new data obtained through radar altimetry, these canyons have been shown to be hundreds of meters deep, and have confirmed rivers of liquid methane flowing through them.

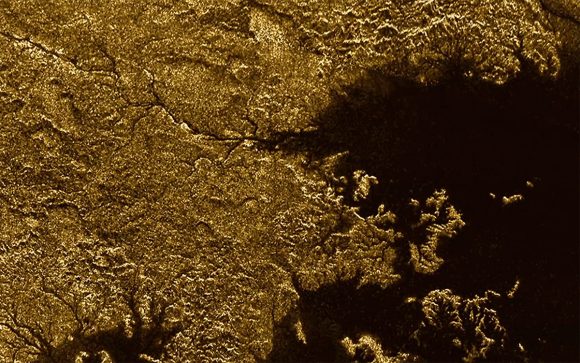

This evidence was presented in a new study titled “Liquid-filled canyons on Titan” – which was published in August of 2016 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. Using data obtained by the Cassini radar altimeter in May 2013, they observed channels in the feature known as Vid Flumina, a drainage network connected to Titan’s second largest hydrocarbon sea in the north, Ligeia Mare.

Analysis of this information showed that the channels in this region are steep-sided and measure about 800 m (half a mile) wide and between 244 and 579 meters deep (800 – 1900 feet). The radar echoes also showed strong surface reflections that indicated that these channels are currently filled with liquid. The elevation of this liquid was also consistent with that of Ligeia Mare (within a maring of 0.7 m), which averages about 50 m (164 ft) deep.

This is consistent with the belief that these river channels in area drain into the Ligeia Mare, which is especially interesting since it parallels how deep-canyon river systems empty into lakes here on Earth. And it is yet another example of how the methane-based hydrological cycle on Titan drives the formation and evolution of the moon’s features, and in ways that are strikingly similar to the water cycle here on Earth.

Alex Hayes – an assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell, the Director of the Spacecraft Planetary Imaging Facility (SPIF) and one of the authors on the paper – has conducted seversal studies of Titan’s surface and atmosphere based on radar data provided by Cassini. As he was quoted as saying in a recent article by the Cornell Chronicler:

“Earth is warm and rocky, with rivers of water, while Titan is cold and icy, with rivers of methane. And yet it’s remarkable that we find such similar features on both worlds. The canyons found in Titan’s north are even more surprising, as we have no idea how they formed. Their narrow width and depth imply rapid erosion, as sea levels rise and fall in the nearby sea. This brings up a host of questions, such as where did all the eroded material go?”

![The northern polar area of Titan and Vid Flumina drainage basin. (left) On top of the image, the Ligeia Mare; in the lower right the North Kraken Mare; the two seas are connected each other by a labyrinth of channels. On the left, near the North pole, the Punga Mare. Red arrows indicate the position of the two flumina significant for this work. At the end of its mission (15 September 2017) the Cassini RADAR in its imaging mode (SAR+ HiSAR) will have covered a total area of 67% of the surface of Titan [Hayes, 2016]. Map credits: R. L. Kirk. (right) Highlighted in yellow are the half-power altimetric footprints within the Vid Flumina drainage basin and the Xanthus Flumen course for which specular reflections occurred. At 1400?km of spacecraft altitude, the Cassini antenna 0.35° central beam produces footprints of about 8.5?km in diameter (diameter of yellow circles). Credit: NASA/JPL](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/grl54735-fig-0001-580x282.png)

However, conditions on Titan do not allow for the presence of glaciers, which rules out the likelihood that retreating sheets of ice could have carved these canyons. So this naturally begs the question, what geological forces created this region? The team concluded that there were only two likely possibilities – which included changes in the elevation of the rivers, or tectonic activity in the area.

Ultimately, they favored a model where the variation in surface elevation of liquid drove the formation of the canyons – though they acknowledge that both tectonic forces and sea level variations played a role. As Valerio Poggiali, an associate member of the Cassini RADAR Science Team at the Sapienza University of Rome and the lead author of the paper, told Universe Today via email:

“What the canyons on Titan really mean is that in the past sea level was lower and so erosion and canyon formation could take place. Subsequently sea level has risen and backfilled the canyons. This presumably takes place over multiple cycles, eroding when sea level is lower, depositing some when it is higher until we get the canyons we see today. So, what it means is that sea level has likely changed in the geological past and the canyons are recording that change for us.”

In this respect, there are many more Earth examples to choose from, all of which are mentioned in the study:

“Examples include Lake Powell, a reservoir on the Colorado River that was created by the Glen Canyon Dam; the Georges River in New South Wales, Australia; and the Nile River gorge, which formed as the Mediterranean Sea dried up during the late Miocene. Rising liquid levels in the geologically recent past led to the flooding of these valleys, with morphologies similar to those observed at Vid Flumina.”

Understanding the processes that led to these formations is crucial to understanding the current state of Titan’s geomorphology. And this study is significant in that it is the first to conclude that the rivers in the Vid Flumina region were deep canyons. In the future, the research team hopes to examine other channels on Titan that were observed by Cassini to test their theories.

Once again, our exploration of the Solar System has shown us just how weird and wonderful it truly is. In addition to all its celestial bodies having their own particular quirks, they still have a lot in common with Earth. By the time the Cassini mission is complete (Sept. 15th, 2017), it will have surveyed 67% the surface of Titan with its RADAR imaging instrument. Who knows what other “Earth-like” features it will notice before then?

Further Reading: Geophysical Research Letters