[/caption]

As one of the planets visible with the unaided eye, Mercury has been known before recorded history. But until the development of the telescope, the exploration of the Mercury was only unaided eye observations. Early cultures like the Mayans and ancient Greeks were diligent astronomers, and calculated the motions and positions of Mercury with tremendous accuracy.

But the exploration of Mercury really began with the invention of the telescope. Galileo Galilei was the first to turn his telescope on the 1st planet, seeing nothing more than a small disk. Galileo’s telescope wasn’t powerful enough to see that Mercury has phases, like the Moon and Venus. In 1631, Pierre Gassendi made the first observations of Mercury’s transit across the surface of the Sun, and further observations by Giovanni Zupi revealed its phases. This helped astronomers to conclude the Mercury orbited the Sun, and not the Earth.

Because Mercury is so small, and located so close to the Sun, astronomers weren’t able image features on its surface with any accuracy. It wasn’t until the 1960s, when Soviet scientists bounced radio signals off the surface of Mercury that astronomers got any sense of what its surface was like. These radio reflections also helped astronomers discover that Mercury’s day length is 59 days; almost as long as its year of 88 days.

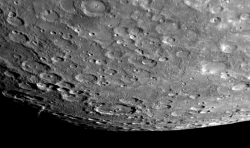

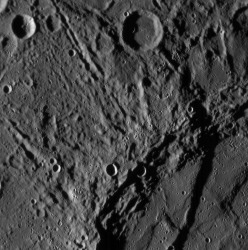

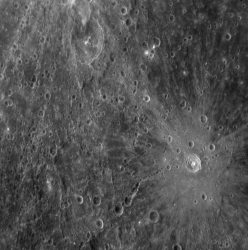

But the best Mercury exploration happened when NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft first flew past Mercury in 1974. It revealed that Mercury’s surface is pockmarked with craters like the Earth’s moon. And like the Moon it has flat regions filled in with lava flows. After two additional flybys Mariner 10 ended up mapping only 45% of Mercury’s surface.

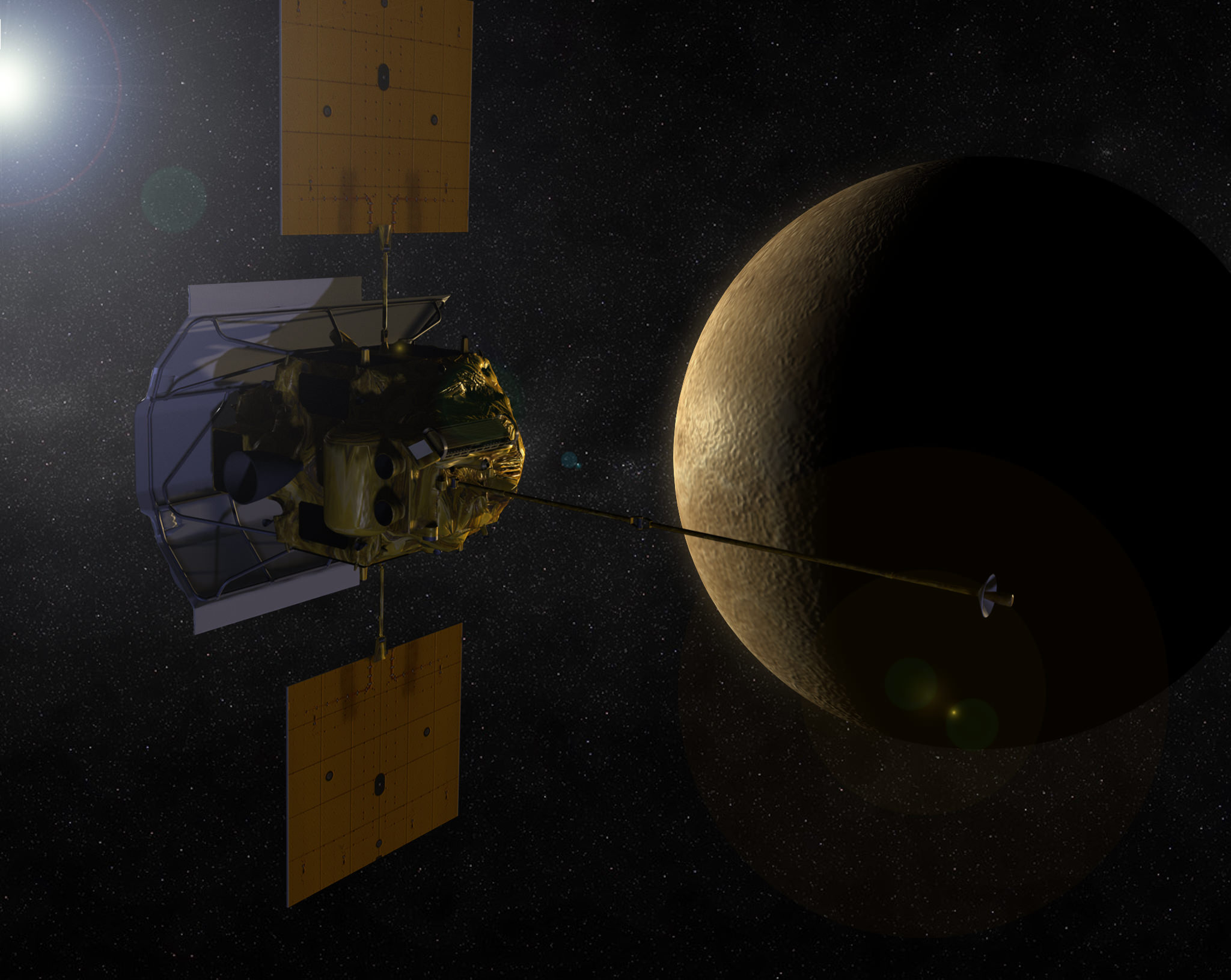

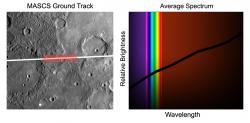

The next mission to explore Mercury was NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, launched on August 3, 2004. It made its first Mercury flyby on January 14, 2008, mapping more of Mercury’s surface. MESSENGER will eventually go into orbit around Mercury, mapping its surface in great detail and answering many unknown questions about Mercury and its history.

We have written many stories about Mercury here on Universe Today. Here’s an article about a the discovery that Mercury’s core is liquid. And how Mercury is actually less like the Moon than previously believed.

Want more information on Mercury? Here’s a link to NASA’s MESSENGER Misson Page, and here’s NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide to Mercury.

We have also recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast that’s just about planet Mercury. Listen to it here, Episode 49: Mercury.

References:

NASA Solar System Exploration: Missions to Mercury

NASA: Planetary Science