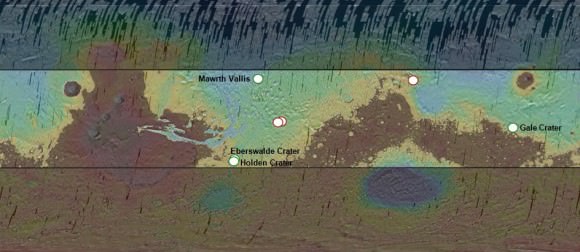

A 150-kilometer-wide hollow on Mars named Gale Crater has emerged as the front-runner for the potential landing site for the Mars Science Laboratory rover, Curiosity, which will head to Mars this fall. Nature News and the Planetary Society Blog report that following a meeting of project scientists last month, Gale came out on top of four different locations as the preferred destination for the next Mars rover. However, the final decision has not been made or announced, and NASA Associate Administrator Ed Weiler has the final word. He is expected to make the final decision on Friday with a formal announcement of the site to follow next week.

[/caption]

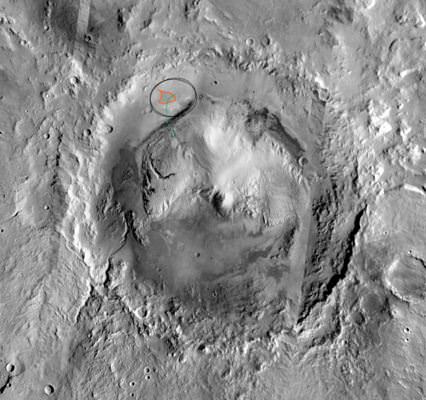

According to planetary scientist Matt Golombek, who was part of the selection committee, Gale Crater has a high diversity of geologic materials with different compositions, created under different conditions. Most interesting is evidence of different minerals arranged in stratigraphical context. “Stratigraphy records multiple early Mars environments in sequential order,” Golombek said at a teleconference for Solar System Ambassadors and Solar System Educators earlier this year. “Gale is characteristic of a family of craters that were filled, buried and exhumed, and will provide insights into an important Martian process.”

The actual landing ellipse is a smooth area with few craters, which is a great and safe place for landing. But the MSL rover – which is the size of a small car – could then take a few 100 sols and head out for more interesting terrain where the sedimentary strata is deposited. There’s a giant 5-kilometer high hill in the middle of the crater, and the rover could traverse up through the lower most layers.

The flythough video of Gale Crater, top, was put together by UnmannedSpaceflight‘s Doug Ellison, who used a mix of HRSC, CTX and HiRISE elevation models, combined with a pair of possible traverse paths for MSL.

The three other choices also have their good points. All the different landing site choices lie between 30 degrees latitude north and 30 degrees south with low elevations – which is a good thing when trying to land on Mars, Golombek said, because that gives you more of Mars’ thin atmosphere to work with. “All the sites are scientifically rich and safe for landing, with small differences between them,” Golombek said.

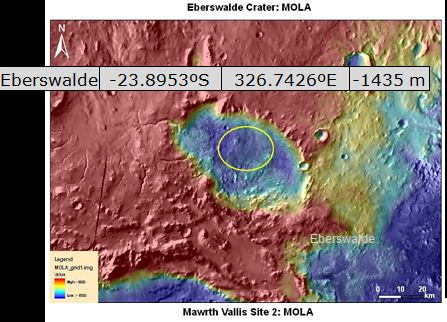

Eberswalde Crater has interesting, rough terrain with flow features that are “clear evidence for a river that entered into a standing body of water at sometime into the past on Mars,” Golombek said. “There’s not much disagreement in science community that this is a ancient delta on Mars.”

This region would provide geologic evidence for how the minerals were deposited and evidence for clay minerals.

“Clays are trappers and preservers of biogenic materials, so going to places where these minerals were deposited in calm water is very enticing,” Golombek said.

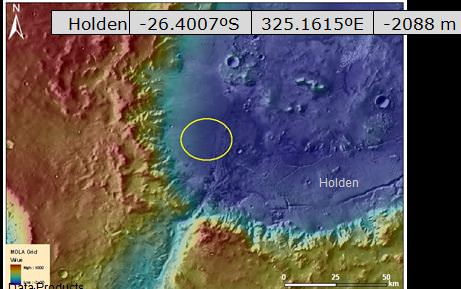

Holden Crater is the smoothest and flattest of the four choices. Southeast of the landing ellipse is an area of minerals that look enticing.

“There are mega breccias – rocks that were thrown up in giant impacts in the earliest days of Mars, so we could study those as well at Holden Crater,” Golombek. “But we’d have to drive pretty far to get there. There are also deposits that were certainly deposited in lake or a relatively quiet fluvial setting.”

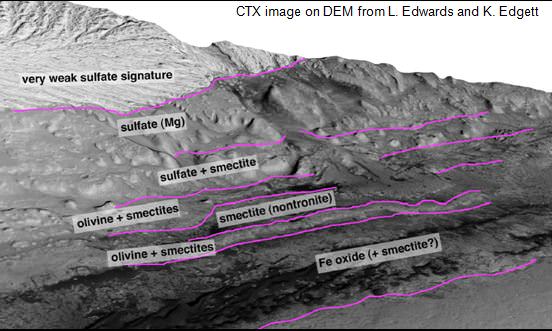

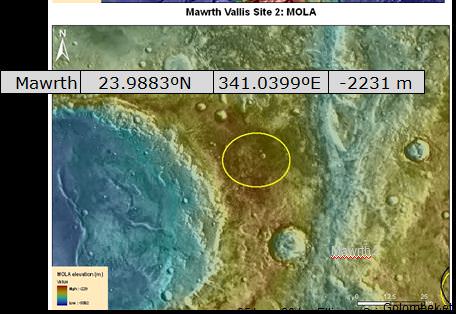

Mawrth Vallis holds complex mineralogy and has some of the oldest and longest sequence of rocks among the four sites and has phyllosilicate-bearing stratigraphy within the landing ellipse. Phyllosilicates, or sheet silicates, are an important group of minerals that includes water-bearing and clay minerals and are an important constituent of sedimentary rocks, which can tell the scientists much about Mars’ past.

Golombek praised the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter mission for providing a extraordinary amount of data to allow the science team to make the best choice.

“The amount of data we have beforehand is unprecedented in Mars exploration,” he said, “with HiRISE(High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment camera) images at 25 cm per pixel, so we can see one meter-size boulders directly on the surface and we have almost complete coverage of the landing ellipses. CRISM (Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars) provides visible and near infrared data to show minearology. The coverage we have is just spectacular.”